Policy framework around outdoor learning in natural environments; government initiatives; and the increasing body of evidence on how outdoor learning improves outcomes.

Outdoor learning is a broad term that includes outdoor play in the early years, school grounds projects, environmental education, recreational and adventure activities, personal and social development programmes, team building expeditions and adventure therapy.

Roger Greenaway, author of research on what constitutes outdoor learning, outlines the common themes that apply across its various forms. These include:

The depth of understanding and knowledge about the education and health benefits for children of outdoor learning is growing, driven in part by concerns over falling engagement with the natural environment for a whole generation of young people and the impact that this is having on reduced levels of physical and mental wellbeing. Greenaway's study was funded by the Institute for Outdoor Learning, which since 2001 has shared evidence on what works, offered good practice advice and helped train educators.

A Natural England study in 2009 found that less than 10 per cent of children play in natural places such as woodlands, countryside and heaths compared with 40 per cent of children in the 1980s. This year, research from the Dirt Is Good campaign found that three-quarters of children spend less time outside than prison inmates.

The reasons for the decline are multiple and complex - they include an increasingly urban population, heightened concern about the perceived risks posed to children from traffic and strangers, the growth in screen-based entertainment, and sales of school playing fields to name but a few.

The government recognises the problem, with a number of Whitehall departments doing work - funding research, developing guidance and testing new interventions - aimed at improving children's access to outdoor activities and green spaces. In March 2016, Environment Secretary Elizabeth Truss pledged that from 2017/18, all school children will be able to visit a national park to increase the numbers experiencing outdoor learning. Under the plan, national park authorities will engage more than 60,000 young people a year through school visits.

The Department for Education's character and resilience agenda has emphasised the role outdoor learning can play in helping young people develop the skills and traits needed to overcome life's challenges and achieve in education and beyond. The recent white paper Educational Excellence Everywhere reinforces this and includes other measures, such as increased freedoms for schools, that could help primaries and secondaries to incorporate outdoor learning more into how pupils learn (see below).

In addition, the Conservative government's 2015 election manifesto included ambitious plans for every 15- to 17-year-old to have the opportunity to take part in the National Citizen Services (NCS) by 2020. A key element of the flagship social action programme - backed by the Cabinet Office - is a week-long outdoor learning residential trip. The numbers participating are increasing quickly with encouraging results for the long-term benefits that it brings (see NCS practice example).

Another initiative receiving government backing is Play Streets, in which the Department for Transport and Department for Communities and Local Government are working together to make it easier for councils to allow residents to regularly close streets to traffic and open them up for children to play. Raising the amount of time children spend exercising and increasing school sports funding - after major cuts under the coalition government - are also key targets for the Department for Health. The childhood obesity strategy is also expected to pull together a range of initiatives to encourage children's participation in outdoor activities, although the six-month delay in its publication has seen ministers and the department criticised.

However, campaigners argue these initiatives are largely piecemeal when what is required is a government-wide strategy for outdoor learning and play. Cath Prisk, former director of Play England and global partnerships manager for Project Dirt, says this void is a particular problem for encouraging participation from the eight- to 13 age group.

"With increasing pressures on childhood, children today are too often overprotected, overscheduled and overly attached to screens. And yet what all parents and teachers want is for children to grow up happy and to develop the skills they need for the future - that's why it is more crucial than ever before to help get children outdoors," Prisk says.

Despite the lack of an overarching government strategy, public bodies, environmental charities and sector-led organisations are developing new ways of engaging children of all ages with the outdoor world and, in so doing, broadening and deepening their education and skills.

Early years play

The Early Years Foundation Stage requires childcare settings to provide access to an outdoor play area or, if that is not possible, ensure outdoor activities are planned and occurring on a daily basis. A survey of 400 providers found outdoor space had in the majority of settings become bigger and improved in quality, with 96 per cent saying outdoor play was "very important".

However, the Early Childhood Forum's survey of outdoor learning provision for under-fives found evidence of lack of outdoor space (18 per cent), negative parental attitudes (26 per cent), insufficient staff training (31 per cent) and inadequate resources (31 per cent) among providers (see research evidence).

A movement that is growing in popularity is that of Forest Schools. These schools and nurseries provide an educational approach to outdoor play and learning in a woodland environment. Their ethos is that the closer children are to nature, the happier they will be and the more they will achieve. Findings from a recent Ofsted inspection of the Woodland Nursery, a Forest School in London, praised the school readiness of the children who attended (see practice example).

School-based approaches

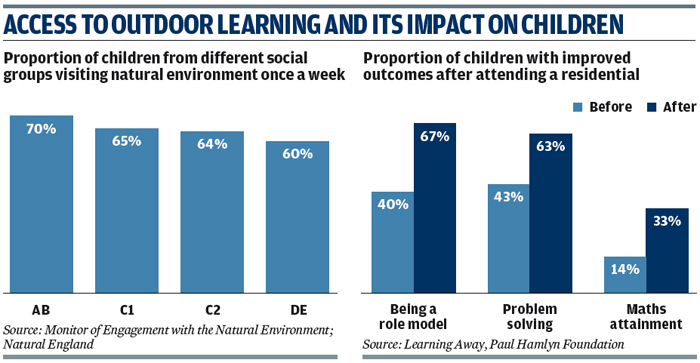

In February, public body Natural England, published the findings from its two-year pilot to develop a national indicator for measuring children's access to the natural environment. It built on measures in the 2011 Natural Environment white paper, which set out the ambition for "every child to be able to experience and learn in the natural environment". The pilot found that over a 12-month period, 88 per cent of children visited the natural environment - the most popular venues being parks, playgrounds and playing fields - mainly with their parents. Children from more affluent families visited the natural environment more than those from disadvantaged backgrounds (see graphic).

Natural England concluded that schools could become an important gateway to outdoor learning and has been developing ways to support schools in disadvantaged areas to improve access to outdoor education. The full findings from the study are to be published shortly, but Natural England hopes the model, piloted in the South West, will be expanded across the country.

The Paul Hamlyn Foundation-funded Learning Away report looked at how schools can use residential experiences as an integral part of the curriculum. A total of 60 schools were studied with experiences including camping, outdoor adventures and urban/rural school exchanges. Outcomes measured included the impact participation had on individual attainment and aspiration, community cohesion and cultural diversity.

Three-quarters of staff surveyed said taking part in a residential had improved students' resilience, confidence and wellbeing, while 23 per cent of parents said their child's school attendance had improved. Pupils who participated also achieved significantly better GCSE grades than their peers.

In addition, outdoor learning experiences helped pupils confront challenges. Two-thirds of year 6 pupils said the experience had made them more confident about meeting new people, with 53 per cent saying they were now excited about the transition to secondary school (see Outward Bound Trust practice example). Teachers said the residential was "worth half a term" in the progress pupils made.

Initiatives such as Empty Classroom Day are taking the outdoor learning message global by creating an event - on 17 June - to celebrate and promote play outside of the classroom. It includes lesson plans and guidance written by experts on how teachers can make the most of outdoor education opportunities.

Youth groups

With much political and state-funded capital being pumped into the National Citizen Service (NCS), the social action programme has become a key outdoor learning experience for many adolescents. In addition, a number of youth organisations operate their own outdoor learning centres, which are used by groups in their network or by schools, local authorities and youth groups from other areas.

YMCA's National Centre in Lakeside is one of the largest outdoor activity facilities in the country. It works with schools, the NCS and youth organisations such as Prince's Trust to deliver experiential learning.

Hindleap Warren Outdoor Centre in East Sussex run by UK Youth provides residential and day courses for children and young ?people from schools, youth groups and organisations that work with young people with additional needs.

PGL also runs a range of residential outdoor learning experiences for uniformed youth groups including the Scouts, Girl Guides, Cubs and Brownies.

However, cuts to local authority youth services has seen the amount of provision offered and commissioned by councils reduce. A recent survey by the English Outdoor Council revealed that out of 152 local authority-run outdoor centres, 26 per cent faced closure, while 39 per cent were at risk.

Social pedagogy

The contribution that outdoor learning can play in tackling social pedagogical issues is also increasingly being recognised. Outdoor experiences can help engage hard-to-reach groups and help them achieve goals and develop skills that they would struggle to do in a formal education setting. This can also offer a springboard for helping young people who have struggled at school to re-engage with education (see Jamie's Farm practice example).

A major study published last November by the University of Derby for the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds, found children who were more connected to nature had significantly higher attainment in English, life satisfaction, health outcomes and pro-environmental behaviours.

Meanwhile, other research has looked at the benefits of outdoor learning for particularly vulnerable groups, such as looked-after children, young offenders and those with disabilities.

A study published in February into a small group of young carers who took part in the Good from Wood project run by social enterprise Nature Workshops identified a range of benefits.

It states: "The young carers… enjoyed the freedom engendered by being outdoors and being able to undertake physical activities in the woods. They developed friendships and reported feeling happier, and were better able to relate to their peers. Their teachers and parents noted that they were more settled and that their behaviour had improved.

"It provided a break from their caring responsibilities. It literally gave them a chance to be carefree; a chance to learn about the woods and themselves, to get muddy and to gain confidence."

Register Now to Continue Reading

Thank you for visiting Children & Young People Now and making use of our archive of more than 60,000 expert features, topics hubs, case studies and policy updates. Why not register today and enjoy the following great benefits:

What's Included

-

Free access to 4 subscriber-only articles per month

-

Email newsletter providing advice and guidance across the sector

Already have an account? Sign in here