Click here to download the full debate as a PDF

Nesta, the UK’s innovation agency for social good, launched its 10-year strategy at the beginning of March. A key pillar of the strategy is for every child to have a fair start, specifically to eliminate the school readiness gap between children born into deprivation and their peers by 2030 (see below). Nesta teamed up with CYP Now to host a virtual debate with sector leaders on 3 March on realising this vision.

Nesta’s work focuses on two crucial periods in the child’s life – the first five years and the period from age 11 to 16, with this debate dedicated to the early years.

The new strategy comes in the wake of stubborn and persistent inequalities that were widening because of cuts to public services which lockdown has made more visible.

Meanwhile, the early years funding crisis appears to be deepening. According to Coram Family and Childcare’s 21st annual Childcare Survey, more than a third of local authorities report that early years providers in their areas have closed during the last year.

Sector leaders used the roundtable debate to shape Nesta’s roadmap for its new strategy and identify opportunities for sector-wide collaboration to close the outcomes gap within 10 years.

Innovation mission

“Too many children start school without the confidence to learn. We are working to remove some of the barriers that stifle opportunities so all children can thrive” said Tom Symons, a deputy director of Nesta’s A Fairer Start mission.

“It’s that question of what’s realistic in terms of the scale, ambition and aspiration of this goal that we want to focus on,” he told attendees.

Symons shared three models for working that will underpin Nesta’s new strategy: as innovation partner, which will see Nesta design, test and scale innovative solutions with partners on the frontline; as system shaper, influencing wider systems of policy and practice to support and promote innovation; and as venture builder, to create, support and invest in early-stage ventures to develop new solutions and shift key markets.

Nesta ran an open process in the autumn to find innovation partners and has now selected three areas to work on a pilot scheme: Leeds, York and Greater Manchester Combined Authority with Stockport Metropolitan Borough Council.

In many cases, unlocking the solution is the struggle; the problem is often known too well to parents and professionals. Nesta will work with local authorities to find a different way into what may often seem like an intractable problem, and develop solutions together. Options being discussed during the early stages of the process include using data science and implementation science to make sense of service provision; using behavioural insights and design to increase parental engagement with services; looking at design and technology to reimagine the home learning environment; and looking for new ideas or new financial models to make the workforce sustainable and reduce staff turnover.

Making sense of the challenge – what is stopping us from closing the gap?

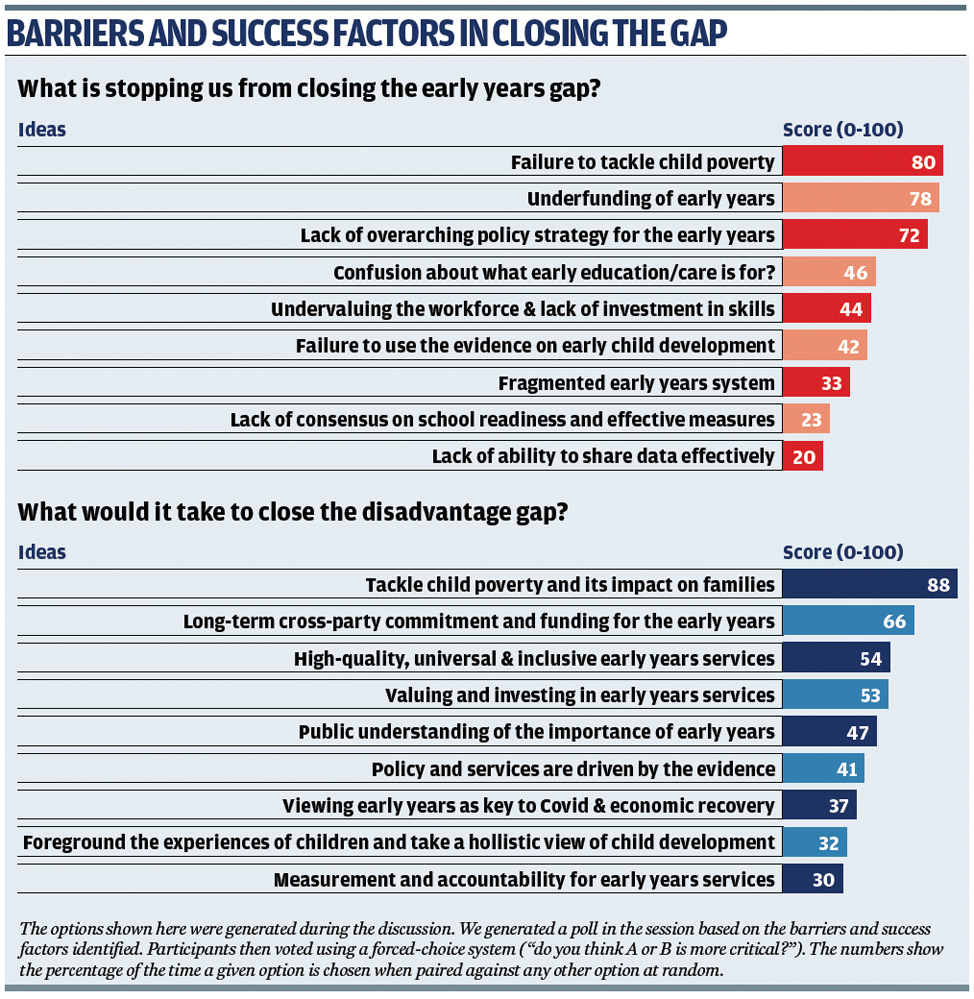

Participants were invited to unload and express “what’s wrong with the world,” specifically the barriers to narrowing the disadvantage gap. The biggest barrier identified was increasing child poverty, exacerbated by the Covid-19 pandemic.

Sarah Newman, bi-borough executive director of children’s services at Westminster, and Kensington and Chelsea Councils, said: “The elephant in the room is always the impact of poverty and what we are doing to address that.”

Professor Chris Pascal, director of the Centre for Research in Early Childhood, said: “Until we tackle these big structural issues of poverty and housing, there will be children who will not achieve and we will never close that gap.”

The pandemic has also highlighted the lack of a long-term strategy for early years, which Early Years Alliance chief executive Neil Leitch believes has left the sector “lurching from one crisis to the next.”

“We have some component objectives, but there is no overarching joined-up thinking. We don’t have a 10-year or five-year strategy, we don’t even have a single-year strategy,” he said.

Jane Barlow, principal investigator for A Better Start at the University of Oxford, cited the disparity between parliamentary support for the 1,001 Days Movement and “a set of economic policies in which more children are finishing up in poverty”.

“We’ve had this movement alongside the closure of children’s centres and all of the things that we recognise to be fundamental to improving outcomes for children.” She added that flaws in the system for commissioning services including a lack of joined-up working “effectively prevents us from ensuring that the most disadvantaged children are school ready.”

Leitch was also one of many participants who said the sector is blighted by “confusion over the purpose of early childhood education”.

“Sometimes it’s about child development, sometimes it’s to support social disadvantage and other times it is nothing more than basically getting parents, predominantly mums, back into the working environment,” he said, highlighting the contrast between early years and post-five education which “we seem to accept is all about the child’s development”.

“Determining why the early years exists is a definite barrier,” Leitch said.

Merle Davies, director of the Centre for Early Child Development, cited “lack of investment” as the “biggest gripe”.

“The funding that goes into early years settings isn’t enough, the way the funding is worked out doesn’t cover costs – we have lots of good providers closing due to lack of funding.

“Also, the funding doesn’t match the need,” she added. “We have three-year-olds with developmental delay – they need the same level of funding as two-year-olds but they don’t get it.”

Octavia Holland, assistant director of the early childhood unit at the National Children’s Bureau, said there is “work to be done” to change the public’s perception of the sector which is currently “undervalued”.

Professor Chris Pascal said barriers were political as much as professional, requiring “hard-edged top-level discussions at Treasury level” to overcome. Until the government listens and recognises “the early years and the value of it, the hidden value of it, I think we will keep seeing the underinvestment and fragmentation, and therefore the continued gap,” she said.

A time to hope – what would it take to close the disadvantage gap in a decade?

The group used these barriers as a platform to share “dream” enabling factors that could be put in place to close the outcomes gap over the next 10 years – ideas that will form the basis for discussions on how Nesta can achieve its goal.

Collectively, participants identified an end to child poverty and its impact on families, a long-term cross-party commitment to an early years strategy, and funding for high-quality universal and inclusive early years services, as the three biggest priorities.

Tracy Jackson, head of early years at Save the Children UK, was among those who called for a focus on the “devastating impact” of poverty on outcomes for young children but said overhauling policies needs to be coupled with “increasing the incomes of the poorest children and families”.

Judith Blake, chair of the Local Government Association (LGA) children and young people board, and the leader of Leeds City Council, said tackling the disadvantage gap in the early years also means confronting a “basic lack of understanding of what good early years looks like.”

“Until we’ve managed to lift that awareness across government and local governments, I don’t think we’re going to get anywhere.”

Others highlighted professional purpose and status and the need to “celebrate early years in its own right” rather than focus on “school readiness” in order to provide high-quality universal and inclusive early years services to support the most vulnerable families.

Jackson said society must “move away from early years being regarded as that period that prepares children for school or it allows parents to work, and invest in that critical period for children in its own right.”

London Early Years Foundation chief executive June O’Sullivan said reshaping early years policy must begin with asking “what a happy childhood looks like”, saying “you cannot change the world if you don’t understand what you’re doing”.

“If you don’t understand what pedagogy looks like and what needs to translate to it in terms of the experience of children, we will get locked in that language of school readiness, which has absolutely nothing to do with true and real pedagogy.

“Let’s celebrate what we already have and start from a positive and not a deficit narrative,” she said.

O’Sullivan also suggested the need for “a national pillar of modern infrastructure, which is properly funded and nationally offered so it’s not an extra, it’s actually a national right to any chance to attend the best-quality nursery”.

Pascal said: “I think a national conversation is needed about what kind of childhood we want to achieve as a society. This is a fundamental cultural and societal debate that never seems to happen. Until we generate some kind of shared national will, we shall continue to struggle with this agenda.”

Dr Jo Casebourne, chief executive of the Early Intervention Foundation, said that a public recognition of early years as a “core public service” like schools and emergency services with targeted support for the most vulnerable would help close the disadvantage gap.

“It would mean that childcare isn’t only treated as supporting parental work, but also as a key part of children’s development,” she said, adding that this would require funding in the government’s next three-year spending review, for evidence-based services targeting vulnerable children.

Casebourne also called for clarity on the future of early help services such as the Healthy Child programme, currently under the remit of Public Health England which is to be replaced by National Institute for Health Protection in the coming months.

“We need to put our money where our mouth is, in terms of prevention and public services,” she said. “Everyone knows that in theory it’s a good thing if you stop problems early before they get worse, and I would argue that the whole of early years does, because we know the lifetime benefits to the economy, let alone to the individuals and families themselves of investing early to close a disadvantage gap.

“But we actually have to get the Treasury really investing in prevention in public services, and not just paying lip service.”

The LGA’s Blake stated: “The funding issue is absolutely critical so that local authorities can fulfil what they do well around early intervention, bringing together all of the different strands around supporting families.”

She added more funding for the early years workforce is crucial to support the most disadvantaged children and families: “Every conversation we have with the decision makers needs to be about recognition of the importance of work in early years and the need for quality investment in staff.”

Workforce engagement

O’Sullivan also praised the early years workforce and called for the sector and politicians to “listen to them and engage with them”.

“I don’t think we truly understand what they do or what’s valued by them. We need to consider that and give some real quick credence and credibility to practice, how do we weave theory, research and practice together in a meaningful way? There are some amazing things we’re doing against all the odds that nobody capitalises on or even talks about, we talk always about top-level policy, we don’t think about system change. We don’t really have a narrative that’s positive.”

Pascal added: “Workforce investment is essential to quality – that can make a difference to the gap. Graduates with professional qualifications in every setting should be affordable and afforded.”

Kate Hoskins, reader in education at Brunel University, cited the importance of training staff to work with children living in poverty in order to address the disadvantage gap. She said: “We know that for young children who are living in poverty they’re going to be coming from really different very diverse backgrounds and their starting points are going to be so different. We need staff with qualifications and confidence in dealing with that.”

She also expressed a need for more qualified staff across all settings and “establishing a standard within the sector” and highlighted the need to “recognise that early years is operating in a hostile policy environment”.

“We have to have long-term funding that is cross-party, so a 10-year plan and a commitment from all the political parties that says ‘yes, this is what we’re going to do to help them support vulnerable families and children in order to get the best sorts of outcomes for them’,” she said.

Eleanor Stringer, head of programmes at the Education Endowment Foundation agreed: “While this is a really challenging year it’s also an opportunity to learn from what happens when kids aren’t having that access to early years.”

She argued that a strong evidence base was crucial to securing much-needed funding and a long-term strategy for the sector.

The sector needs funding and policy decisions that are based on “crystal clear” evidence detailing how the sector is “improving health outcomes and improving welfare”, Stringer explained.

Harriet Waldegrave, senior public affairs and policy analyst at the Office of the Children’s Commissioner for England, added that stronger evidence to showcase the importance of early years would mean the sector is “seen as seriously as schools”, but there is a lack of measurement and accountability. She said: “There’s no way to go from nought to five, [and identify] what happened well for this child, what happened badly? We know half of local authorities can’t even say if a child went on to get other help if needs were identified at two-and-a-half.

“There is no way to hold the system to account,” which she said falls short of demands from the Treasury to know what is “working overtime, continually”.

Hoskins added that recognising the holistic work offered by early years through research could be used as leverage to access more funding from government.

“It’s really important to look at the holistic work that the early years do. It is about supporting the child, but also it’s about supporting the family,” she said.

“In my research, we found that our early years settings were filling welfare gaps, and this was before the pandemic and in the context of austerity and constant cuts to local funding. It’s important to recognise that they provide material support and they need funding in order to do that really important work.”

PARTICIPANTS

- Ravi Chandiramani, Publisher, Children & Young People Now

- Elspeth Kirkman, Chief Programmes Officer, Nesta

- Louise Bazalgette, Deputy Director, A Fairer Start, Nesta

- Tom Symons, Deputy Director, A Fairer Start, Nesta

- Sara Bonetti, Director of Early Years, Education Policy Institute

- Merle Davies, Director, Centre for Early Child Development

- Neil Leitch, Chief Executive, Early Years Alliance

- Sarah Newman, Executive Director, Bi-Borough Children’s Services, Royal Borough of Kensington & Chelsea and the City of Westminster

- Edwina Grant, Executive Director of Education and Children’s Services, Lancashire County Council

- Kate Hoskins, Reader, Education, Brunel University

- Harriet Waldegrave, Senior Public Affairs and Policy Analyst, Office of the Children’s Commissioner for England

- June O’Sullivan, Chief Executive, London Early Years Foundation

- Tracy Jackson, Head of early years, Save the Children UK

- Dr Jo Casebourne, Chief executive, Early Intervention Foundation

- Jane Barlow, Principal Investigator, A Better Start, University of Oxford

- Gail Tolley, Strategic Director, Children and Young People, Brent Council; and Chair of ADCS Educational Achievement Policy Committee

- Judith Blake, Chair, Children and Young People Board, Local Government Association; and Leader, Leeds City Council

- Eleanor Stringer, Head of Programmes, Education Endowment Foundation

- Octavia Holland, Assistant director, Early Childhood Unit, National Children’s Bureau

- Professor Chris Pascal, Director, Centre for Research in Early Childhood

ABOUT NESTA AND ‘A FAIRER START’

Nesta’s strategy to 2030

Nesta is the UK’s innovation agency for social good. We design, test and scale solutions to society’s biggest problems.

In our new 10-year strategy, we will focus on three innovation missions: a fairer start for every child; a healthy life for all, and a sustainable future where the economy works better for people and the planet.

For over 20 years, we have worked to support, encourage and inspire innovation. We work in three roles: as an innovation partner working with frontline organisations to design and test new solutions, as a venture builder supporting new and early stage businesses, and as a system shaper creating the conditions for innovation.

A Fairer Start

Nesta’s vision is for every child to have the fairest possible start in life, so they can thrive and realise their potential.

Inequalities appear early, often growing wider over time and having long-lasting effects. But it doesn’t have to be that way. If children and their families get the right support, particularly at crucial points in childhood, then it is possible to change lives for the better.

By 2030, our goal is that the UK will have eliminated the school readiness gap between those born into deprivation and their peers, with similar gains at age 16 among students receiving free school meals.

We know the task ahead is daunting, but inequality isn’t inevitable. Nesta focuses primarily on two crucial stages: the first five years and the period from age 11-16.

We work in partnership with families, communities and professionals to design, test and scale innovative ideas that aim to level the playing field.

By applying our expertise in innovation we find insights hidden in data, build a deep understanding of how families make decisions for their children, identify creative ways to improve services, and rigorously evaluate everything we do to find out if it works, to what extent, and for whom.

- Find out more at nesta.org.uk/2030-strategy