Penalty of a summer birthday

Charlotte Goddard

Thursday, June 29, 2017

Research shows summer-born children do less well academically throughout school, impacting on their life chances. Charlotte Goddard looks at how professionals and policymakers are tackling the problem.

Two years ago, education minister Nick Gibb urged schools and local authorities to take immediate action to ensure summer-born children could start in reception class at the age of five, rather than when they had just turned four. At the time he promised legislation would follow, but so far there has been no further action, to the disappointment of many parents across the country.

Admissions regulations already state that parents can keep children out of school until compulsory school age - which is the start of the school term following their fifth birthday - but many authorities insist that summer-born children move straight into a year 1 class, potentially missing up to a year of schooling and joining a class where friendship groups are already established. Amendments to the admissions code dating from 2014 left the decision of which year to place a five-year-old in up to the local authority, taking into account the best interests of the child. But parents say some local authorities demand from them expensive professional evidence as proof.

The new laws promised by Gibb would also prevent schools insisting children who had delayed entry to school must skip a year later on, for example moving them directly from year 5 to year 7. Gibb has told parliament that delays in legislation are down to the need to find out more about costings, but in the meantime a postcode lottery is in operation.

According to the National Association of Head Teachers (NAHT), some local authorities - such as Liverpool, Wandsworth and Devon - now allow summer-born children the automatic right to enter reception class at compulsory school age without any requirements for parents to provide reasons and evidence. Pauline Hull, lead campaigner of the Summer Born Campaign group, says: "Then on the other hand, you have councils and schools who disagree with the flexible approach, and anecdotally it seems there are others who were following Nick Gibb's advice, but because of the delay have now gone back to what they were doing before."

The House of Commons Education Select Committee carried out an evidence check in 2015 on the school starting age and concluded that while individual cases vary, research consistently shows summer-born children - those born between 1 April and 31 August - tend to do less well at school than their peers. At Key Stage 1, for example, the proportion of summer-born pupils achieving the expected level for writing is 10 percentage points below the proportion of autumn-born pupils; for reading it is eight percentage points below, and seven percentage points for maths. In 2010, government-commissioned research found that 10,000 summer-born children fail to achieve the required standard at GCSE each year, solely because they are the youngest pupils sitting the exams.

Special educational needs

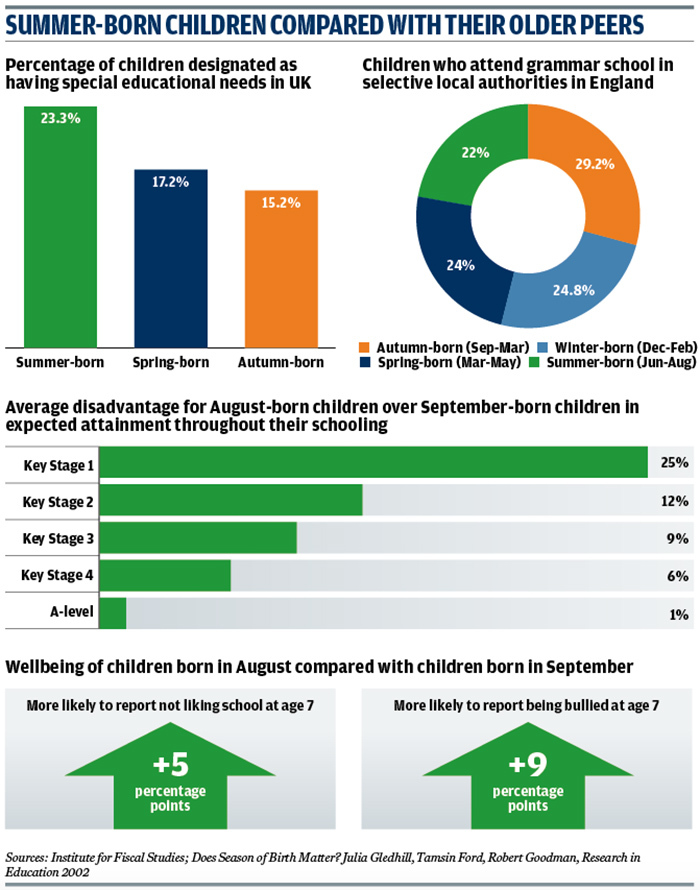

Summer-born children are also more likely to be identified as having special educational needs (SEN), with one study finding that 23 per cent of British summer-borns were classified as having SEN compared with 15 per cent of autumn-borns. Research from the Institute for Fiscal Studies has also found summer-born children are two-and-a-half times more likely to report being unhappy at school, and twice as likely to report being bullied at the age of seven (see box).

However, a recent paper by academics from the University of Exeter Medical School found that while the youngest children in the class had marginally more mental health issues than their older peers, relative age had no impact on children's behaviour or happiness at school. "Education and mental health practitioners should be aware that relative age [the month of the year they were born] may be an additional risk factor for those struggling with multiple difficulties, but our findings suggest it is unlikely to significantly affect on individual child's mental health in isolation," the report concludes.

Courtenay Norbury, Professor of Development Language & Communication Disorders at University College London, has researched factors that exacerbate or reduce the disadvantage faced by summer-born children. She says that children's ability with language is the best predictor of early attainment. This puts younger children, developmentally behind their older peers, at a disadvantage - even in subjects such as maths and PE. A change in the curriculum, with reception year focusing on language development, would benefit all young children, she maintains. "Younger children were also rated as having more symptoms of behaviour problems," she adds. "Language is a helpful tool for regulating your emotions - you can tell a teacher someone is upsetting you instead of hitting them."

The current median school entry age in England - four-and-a half - is one of the earliest in the world. Reception teachers are coming under increasing pressure to prioritise literacy and numeracy, to maximise attainment further up the school. "At this age children should be learning through play," says Professor Norbury. "We should not be asking four-year-olds to do things every day that they are not developmentally ready to do." Repeated failure to achieve tasks can have an impact on children's mental health as well as their confidence and desire to try new things, she says.

Streaming by ability

Streaming children by ability can have the effect of widening the attainment gap in the early years. The London School of Economics' Tammy Campbell is author of a study on summer-born children and attainment. "My research suggests that teachers' views are less polarised by relative age when there is not in-class ‘ability' grouping," she says. "Avoiding classifying children in this way early in their schooling, when they are so young and at different developmental stages, may help prevent differentiated trajectories."

Best-practice strategies designed to support all young children, including home visits before school starts, flexible hours, and allowing parents into the classroom to settle their children, will particularly benefit summer-borns. Lyndhurst Infant School in Worthing, for example, allows spring and summer-born children to start reception on a part-time basis if their parents want them to. Children who experience difficulties starting school will have their own transition plan drawn up in partnership with parents and carers, and staff visit local pre-schools with a book about the school to share with the setting. Pre-schools that send large groups of children to Lyndhurst also have school uniforms, book bags and lunch boxes for the children to role-play with.

Classroom layouts should include comforting places where children can retreat to if everything becomes too much, and strong links between early years providers and schools can make transitions easier. Summer-born children, who would be in a nursery environment with a higher ratio of adults to children if their parents chose to defer their entry, particularly benefit from a higher number of adults in the classroom, such as teaching assistants.

Lynn Knapp is head teacher of Windmill Primary School in Oxford. "We have three-form entry, so we are able to organise children by age," she says. "We can cater for that year of emotional development that younger children have missed by the way we organise the classroom and the structure of the day, with more time to rest in the afternoon, for example. The summer-born children have the same learning opportunities, they have to reach the same outcomes at the end of the year, but the approach is different."

Surrounding children with peers of the same age can help give much-needed confidence. After the first year, classes are mixed but the school tracks the attainment of summer-born children as a group in the same way they would track other groups such as those eligible for the pupil premium. "When we track children, the gap between autumn- and summer-born has reduced, so we have evidence that our approach does work," says Knapp.

Some experts, including the National Foundation for Educational Research, say the most effective way to solve the "birthdate penalty" for summer-born children would be to introduce age-standardised tests. These would make it explicit that an August-born child who reaches the level expected of their September-born classmate is not average, but is working a year ahead of expectations. It has also been suggested that summer-born children should take GCSEs six months later than their peers, but the NAHT says this is unfeasible.

It is not just teachers and schools that need to be aware of the disadvantages faced by summer-born children. Josie Anderson is senior policy and public affairs officer at Bliss, the charity for babies born prematurely. These children are particularly affected by the "birthdate penalty", since they develop according to their due date, rather than their actual birthdate. "In the current system parents are often asked for evidence to justify why children should be delayed, and having other professionals, such as a speech and language therapist or neonatologist on board can be really important," she says.

Last month's general election put everything on pause, but campaigners are hoping the promised admissions legislation will see the light of day before the end of the year. Not all parents will seek to delay their summer-born child's schooling however, and both researchers and practitioners agree that the current trend for increasing formalisation of early education also needs to be reversed, if the disadvantage facing the very youngest children is to be eradicated.

THE ATTAINMENT OF SUMMER-BORN CHILDREN

Children who are born in the summer months do significantly worse at school than their autumn-born peers in England, according to a study from the Institute for Fiscal Studies. The differences are most marked when children first start school, but although they decrease with time there is still a significant gap at the end of compulsory education. In addition, even when summer-born children have caught up with their peers, they are still more likely to say that their attainment is not as good. However, the researchers found little evidence that detrimental effects persisted into adulthood.

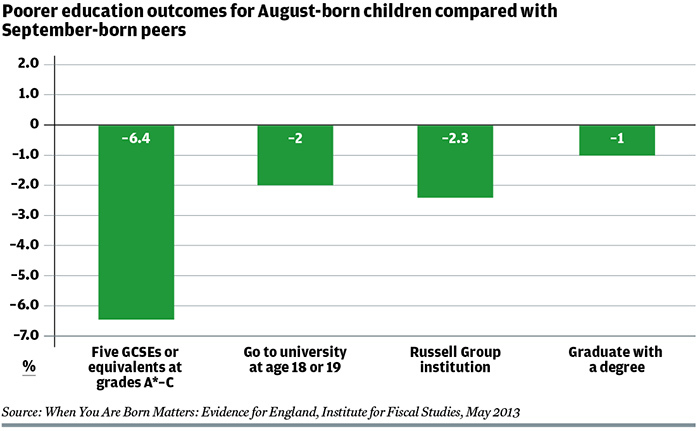

Children born in August are 6.4 percentage points less likely to achieve five GCSEs at grades A* to C than their September-born classmates, found the research. They are two percentage points less likely to go to university aged 18 or 19 and if they do go to university they are around 2.3 percentage points less likely to attend a high-status Russell Group institution and around one percentage point less likely to graduate with a degree.

At age 11, August-born children are 5.4 percentage points more likely to be labelled as having mild special educational needs than September-born children. They are also significantly less likely to believe their own actions make a difference, and more likely to engage in risky behaviours such as underage smoking.

The study recommends age-adjusting national achievement tests to ensure summer-born children are not disadvantaged, but does not support flexibility over the age at which children start school. It calls for schools and parents to be made more aware of the potential disadvantages that children born later in the academic year may face, and more sharing of best practice.

A study from the Institute of Education looked at how a child's month of birth affected which "ability set" they were placed in at school. The report found a pronounced tendency for relatively older pupils in a school year to be placed in the highest stream, set, or group and less likely to be put in middle or lower ability groups. Children born in September are more than twice as likely to be in the highest stream as those born in August, while August-born pupils are more than twice as likely to be in the lowest ability group as those born in September.

The report author concluded streaming can entrench the attainment gap between summer-born children and their peers, demotivating summer-born children and making them feel they are less able, as well as lowering teachers' expectations. The research found greater variation in academic attainment among pupils born at different times of the year who attended schools with "ability sets" than among those attending schools that did not.

KEY STUDIES

- When You Are Born Matters: Evidence for England, Institute for Fiscal Studies, May 2013

- In-school Ability Grouping and the Month of Birth Effect - Preliminary Evidence from the Millennium Cohort Study, Institute of Education, March 2013

HOW TO ADDRESS THE ‘SUMMER-BORN PENALTY'

By Professor Stephen Gorard, Professor of education and public policy, Durham UniversityIn England, children generally attend school with an age cohort where the oldest was born on 1 September of one year and the youngest was born almost a year later on 31 August. This matters because the precise age of a child within their school year is strongly linked to attainment, later life, and wider personal development. In England, 49 per cent of summer-born children who start school in September having just turned four achieve a "good level of development" in their first year, compared with 71 per cent of autumn-born pupils, who are nearly five when they start. The oldest children in any cohort achieve about 25 per cent higher than the youngest at Key Stage 1 (aged 7), and are about 13 per cent more likely to gain the equivalent of five "good" GCSEs with English and maths at Key Stage 4 (aged 16). The younger ones are entered for fewer examinations, are less likely to pass the entrance test for a grammar school, and 10 per cent less likely go to university. By 18, the young person has had 12 or more years of schooling as the youngest, least mature, and maybe the smallest person in their year. Summer-born pupils are somewhat less likely to be picked for competitive sports, more likely to be bullied, and to have lower self-esteem. Age-in-year clearly matters.

These differences in outcomes cannot be explained by the other characteristics of the children. For example, younger children are no more likely to be boys, from less-educated families, specific ethnic groups, or poorer areas - all of which are also factors related to differences in attainment. However, they are more likely to be labelled as having a special educational need (SEN) and a statement of that SEN. They are also more likely to be labelled as having English as an additional language. These facts all suggest teachers and other practitioners are mistaking relative immaturity leading to lower attainment as learning or language difficulties - a very serious indictment of the system.

Changing the cut-off date for entry to school would not solve this problem. For example, using 1st January would simply convert the problem into one concerning autumn-born children (the new youngest in their year). Having two or more age cohorts per year, with one starting in September and one in February perhaps, might reduce the impact of age slightly, but the problem itself would remain. And this approach would be expensive and disruptive.

Allowing parents to delay starting school for their child might help those individuals but would penalise all others to the same extent. If a child who would have been the youngest delays for a year they now become the oldest, and another child becomes the youngest in their year. The situation is zero-sum for the school system and for society, and would probably lead to many parents delaying school for their child just to be safe thus making the delay pointless.

The issue for attainment could be solved quite simply, by routinely age-standardising all attainment scores. This would mean pupils still sitting annual tests at the same time, but with the results adjusted for their precise age. These would form the official record for educational decisions by schools, universities, employers, individuals and family. Age-in-year could become an indicator for contextualised admissions to university, and used as a variable when assessing progress at school by Ofsted and others. Some assessments are already age-standardised, but perhaps not accurately enough, and later examination results are not age-standardised at all.

Teachers and other practitioners need more initial training and professional development to recognise the problem and how to handle its consequences beyond formal assessments alone. With other activities in schools, including sports, you can use vertical and other groupings to reduce the impact of always being the youngest. However, such solutions and interventions need to be robustly evaluated to check they do indeed reduce the summer-born penalty.