Youth sector on a ‘knife-edge' as third of organisations at risk

Neil Puffett

Monday, April 15, 2013

Many youth projects across England and Wales are bracing themselves for the possibility of closing their doors to young people, while others seek new income sources to survive, a CYP Now survey shows

One in three organisations that provide services to young people face closure within the next 12 months, a CYP Now survey has found.

The situation confirms the hostile climate for youth work as local authority cuts are passed on to frontline projects.

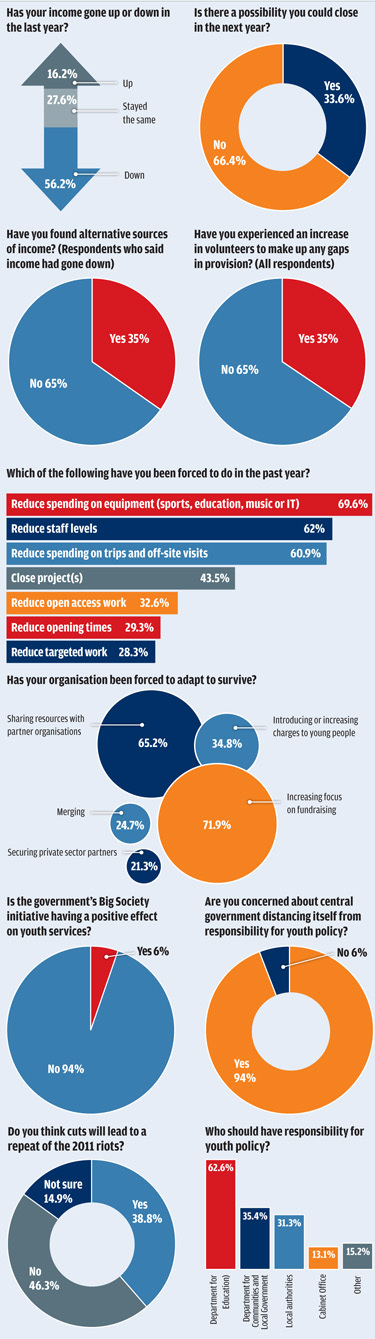

Reflecting the dire financial situation, 56.2 per cent of respondents said their income had fallen in the past year, while 27.6 per cent said it had stayed roughly the same and 16.2 per cent reporting an increase.

When asked if it was possible that their youth project will close in the next year, 33.6 per cent of respondents said “yes”.

In total, 110 professionals responded to the online survey, among them chief executives, project officers and youth development workers. Together, they represent services that work with more than 300,000 young people in England and Wales.

Survival measures

Organisations at risk of closure include one in the South East that works with 10,000 young people. In total, 11 projects that work with more than 1,000 young people are under threat, plus another 21 that work with less than 1,000.

London has the highest number of at-risk projects (seven), followed by the West Midlands and Yorkshire & Humber regions ?(six each). Only 13.9 per cent of organisations facing closure had experienced an increase in volunteers.

To survive, youth projects have also been cutting back on what they provide. More than two thirds – 69.6 per cent – have reduced spending on new equipment. Staff levels have been slimmed down in 62 per cent of services and 60.9 per cent have cut back on trips and off-site visits.

Open access youth work has been reduced in nearly a third of services and 28.3 per cent have wound down their targeted work.

Charlotte Hill, chief executive of UK Youth, says the prospect of a third of projects shutting shows how the sector is now operating on a “knife-edge”.

“It is concerning to see some of the ways projects have been affected, such as having to reduce opening hours and charging young people,” she says.

“Effectively, the cuts the government is making, whether at central or local level, are being passed on to young people at a time when they are already struggling financially themselves.”

The survey did find that youth services have been looking to develop new sources of income, with 71.9 per cent increasing their focus on fundraising and 65.2 per cent sharing resources with partner organisations to make their money stretch further.

Just over a third – 34.8 per cent – have either introduced or increased charges for the young people who use their services. Nearly one in four are merging with other projects and 21.3 per cent have secured support from the private sector.

Of the 35 per cent that had replaced lost income with alternative funding, three-quarters had increased their fundraising efforts and nearly two-thirds were sharing resources with partner organisations, while 30 per cent had secured help from the private sector.

However, the majority of projects – 65 per cent – say they have been unable to secure enough alternative income to cover the drop in funding experienced.

Susanne Rauprich, chief executive of the National Council for Voluntary Youth Services, says it is encouraging that despite the economic gloom, nearly one in five projects reported an increase in income and one in three had been able to find alternative revenue streams.

Alternative sources cited by respondents include payment-by-results projects, additional fundraising events, “business partnership” arrangements, commissioning out projects, use of reserves and legacy funding.

“We need to hear more from organisations that have had success so these successes can be shared right across the sector,” Rauprich says. “It is devastating to look at figures saying 33.6 per cent think there is a possibility they could close in the next year.

Former children’s minister Tim Loughton says the “one bit of good news” from the survey is the evidence of resources being shared with partner organisations and mergers taking place. “We have too many youth organisations working in silos, where we have some large youth sector charities fishing in the same pond and featuring the same departments within their structures,” he says.

The survey also found that despite reductions in staffing, a third of respondents have had an increase in volunteers to help make up gaps in provision.

Youth work at risk

However, an overwhelming 94 per cent say that the government’s Big Society initiative is not having a positive effect on youth services.

One respondent said it just means “there are more volunteers available to replace staff”.

On the wider implications of the cuts, respondents were split on whether reduced youth services could result in civil unrest like that seen in cities across England in August 2011. A total of 38.8 per cent think there could be a repeat of the 2011 riots, while 46.3 per cent believe there will not be, and 14.9 per cent say they are not sure.

The vast majority of respondents – 94 per cent – say they are concerned about central government distancing itself from youth policy.

In January, Education Secretary Michael Gove told MPs on the education select committee that youth policy is not a priority for central government and should be developed by local authorities rather than Whitehall.

Last month, he revealed that the government is considering shifting responsibility for youth policy from the Department for Education to the Department for Communities and Local Government (DCLG).

One respondent to the survey says that moving oversight of national youth policy out of the Department for Education would revert youth work back to the days of pre-state intervention prior to the publication of Circular 1486 entitled In the Service of Youth in 1939, which is widely accepted as marking the beginning of the youth service in England.

“The voluntary sector could flourish, but in the modern concept it will be out-muscled by private sector companies taking on the work with nothing but a cursory commitment to young people, employees, health and safety, and safeguarding,” said the respondent. “It will be a quick buck for an agenda defined by seeing young people as a problem rather than an opportunity.”

Another said: “Without a clear idea of what constitutes a youth offer from central government, local authorities will continue to set their own agenda and youth work will be at risk.”

Loughton says devolving responsibility for youth services to local authorities is “absolutely the wrong way to go”. “At a time when youth services are being disproportionately targeted by local authorities, there needs to be a strong voice and strong advocacy for positive aspects of youth services and that has to be done at a national level,” he says.

Respondents were split on where responsibility for youth policy should lie. The Department for Education was the favoured home for 62.6 per cent, although 35.4 per cent felt the DCLG should play some part. Nearly a third – 31.3 per cent – said there is a role for local authorities and 13.1 per cent believed the Cabinet Office should have a role.

Survey results: What respondents said about the future of youth provision