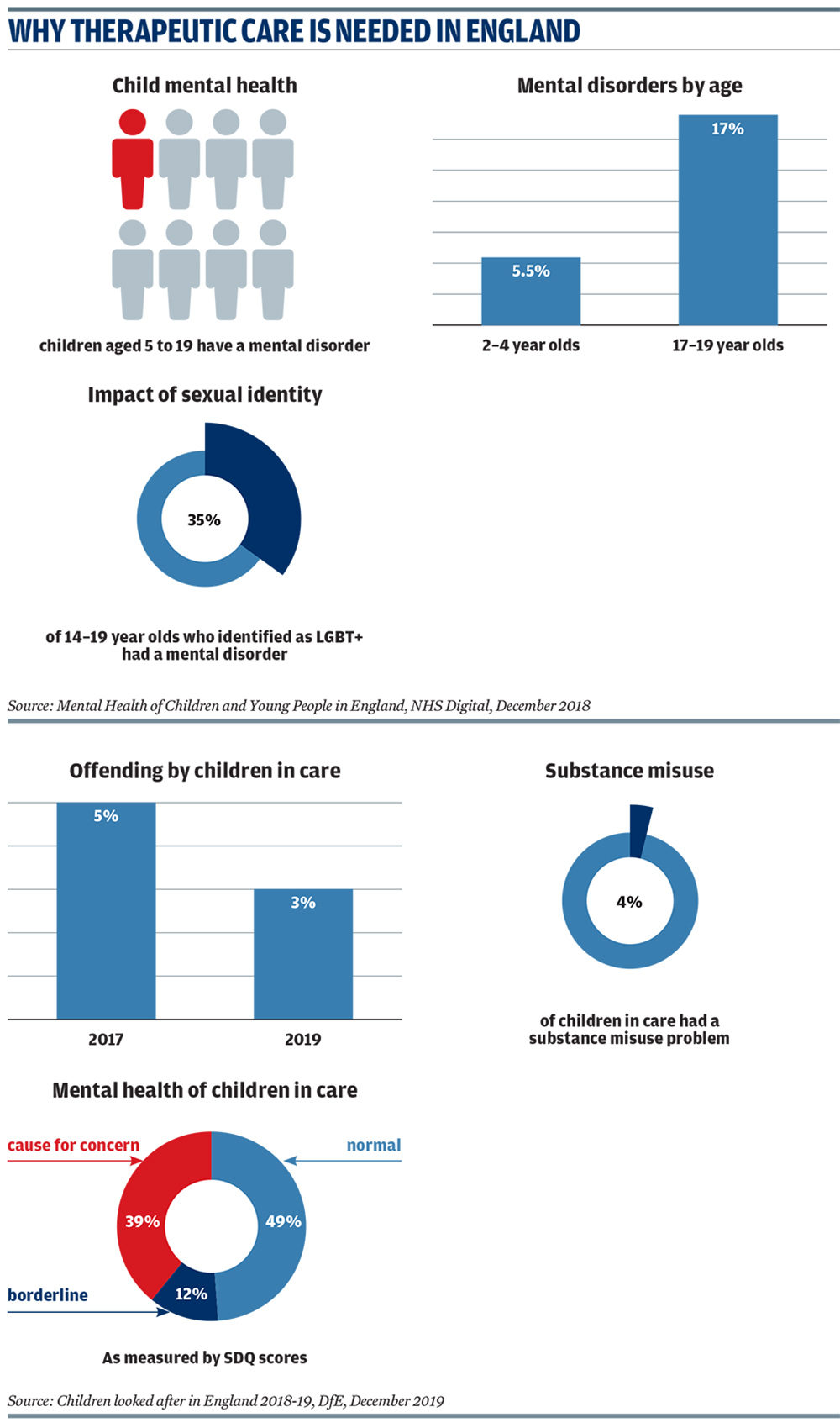

Some groups – such as looked-after children, those struggling with their sexual identity, and young people with special educational needs and disabilities (SEND) – are more at risk of developing a mental health disorder than their peers (see graphics). Meanwhile, the NHS figures show that the prevalence of mental health conditions peaks in adolescence and the mid- to late-teens – this is significant for children’s services, as the largest proportion of children in care are aged 10-15 (39 per cent) and 16+ (24 per cent).

The pressure on children’s services to provide mental health support is growing as a result of a record number of children in care – 78,150 on 31 March 2019; year-on-year rises in children with a SEND education, health and care plan; and three quarters of children with a mental health condition not being referred for treatment.

Register Now to Continue Reading

Thank you for visiting Children & Young People Now and making use of our archive of more than 60,000 expert features, topics hubs, case studies and policy updates. Why not register today and enjoy the following great benefits:

What's Included

-

Free access to 4 subscriber-only articles per month

-

Email newsletter providing advice and guidance across the sector

Already have an account? Sign in here