The vast majority of these children live in residential children’s homes in placements commissioned, and in some cases provided, by local authorities.

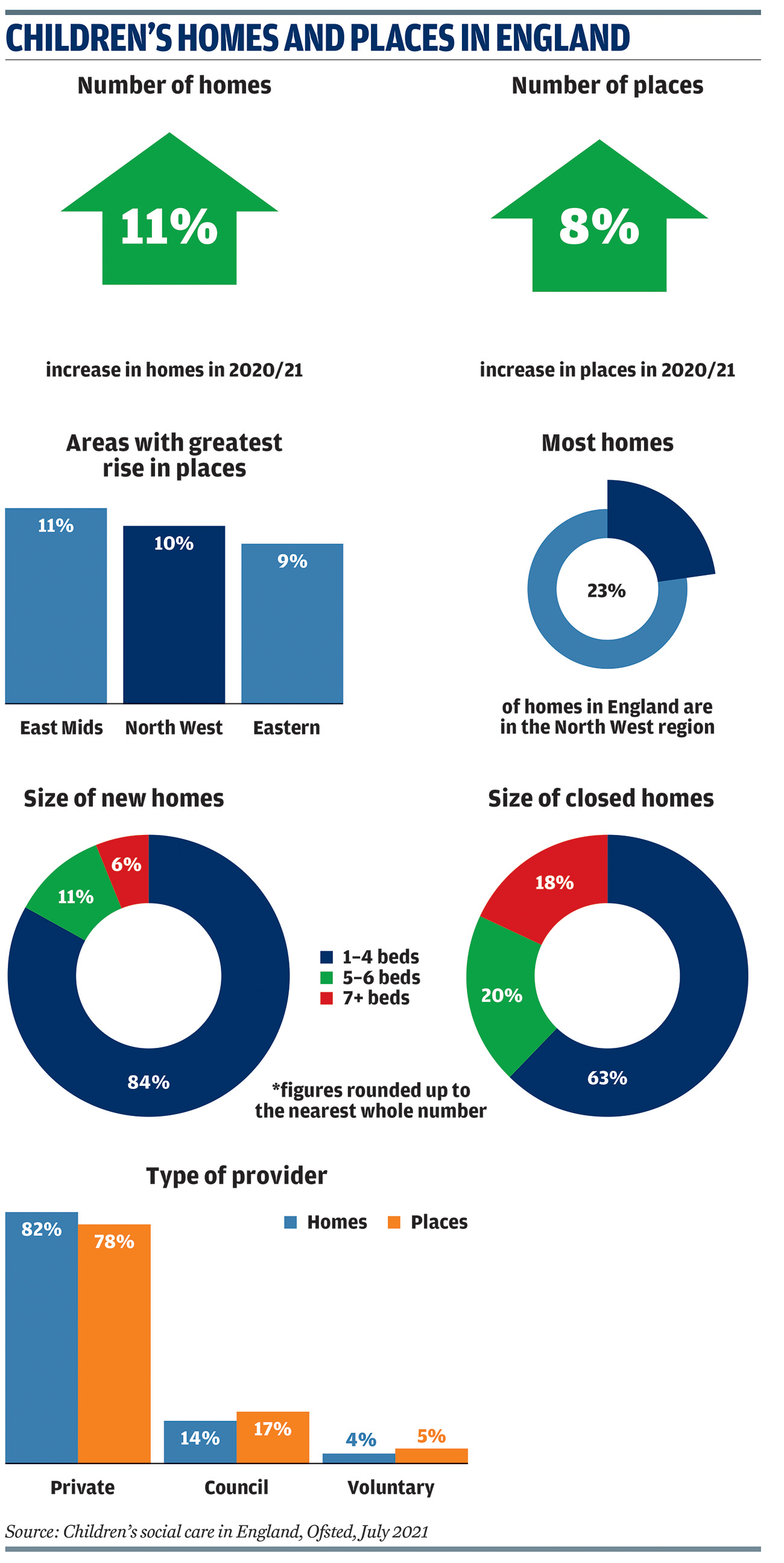

Ofsted data shows the growth in the number of children’s homes and places gathered pace in 2020/21. An additional 346 homes providing 1,155 more places were created in the year to 31 March, a rise on the previous 12 months (see graphics). When factoring in home closures over theyear, there were net gains of 251 homes and 703 places.

All regions saw a rise in the number of homes, while six regions – the North East, Yorkshire Humber, East Midlands, North West, South West, London and East of England – recording rises greater than or equal to the 11 per cent national increase. The East Midlands, North West and East of England saw the greatest rise in places. There is still a huge regional divide in where homes are located, with nearly a quarter in the North West and just four per cent in London.

Register Now to Continue Reading

Thank you for visiting Children & Young People Now and making use of our archive of more than 60,000 expert features, topics hubs, case studies and policy updates. Why not register today and enjoy the following great benefits:

What's Included

-

Free access to 4 subscriber-only articles per month

-

Email newsletter providing advice and guidance across the sector

Already have an account? Sign in here