A radical new model for the purchase of residential and foster care services for children and young people in care is needed, one which supports good-quality care for vulnerable children, is designed for these services and supports value for money. Waiting until the outcome of current reviews into the system is unrealistic because the situation now is critical.

Current procurement legislation is inappropriate and failing authorities, providers and children.

The law is a major factor in the inability of authorities to commission and procure high-quality external provision at an affordable cost, though it is not the only reason.

The suggestions in the green paper Transforming Public Procurement are generic and flawed. The consultation model is for procurement of these services to be absorbed into a new and supposedly less bureaucratic approach for all procurement. It seems to be based on the existing model for social care in the public contracts regulations 2015 (PCR), which introduced extensive regulation for social care for the first time. Replicating this as a future model is the antitheses of the green paper's expressed goal to “speed up and simplify… procurement processes”.

Prior to the PCR, an open market advertisement was not required before a council purchased a service. Now, all contracts with a value of £660,000 or more must be advertised with a public contracts compliant open market process and even those with a value of £25,000 or more must be advertised.

The current rules have coincided with escalating costs which are well above inflation (see Research Evidence section), insufficient places in the market and a failure to meet increasing demand.

Purchasing models

Current purchasing models are exacerbating the problems. The current multi-authority buying consortia, recommended by successive government reviews, are failing. Typically, these purchase services using an uncommercial, overly complex, adversarial approach, using documents which are often substantially based on the authority's generic document and drafted by officers from a number of authorities, not one team. There is no commitment to purchase any specific place. They are a disincentive to social value, collaboration, provider investment and trust. Lack of trust is illustrated by public statements accusing providers of making excessive profits, which is not conducive to the development of a healthy supply chain even if some are justified.

Better outcomes

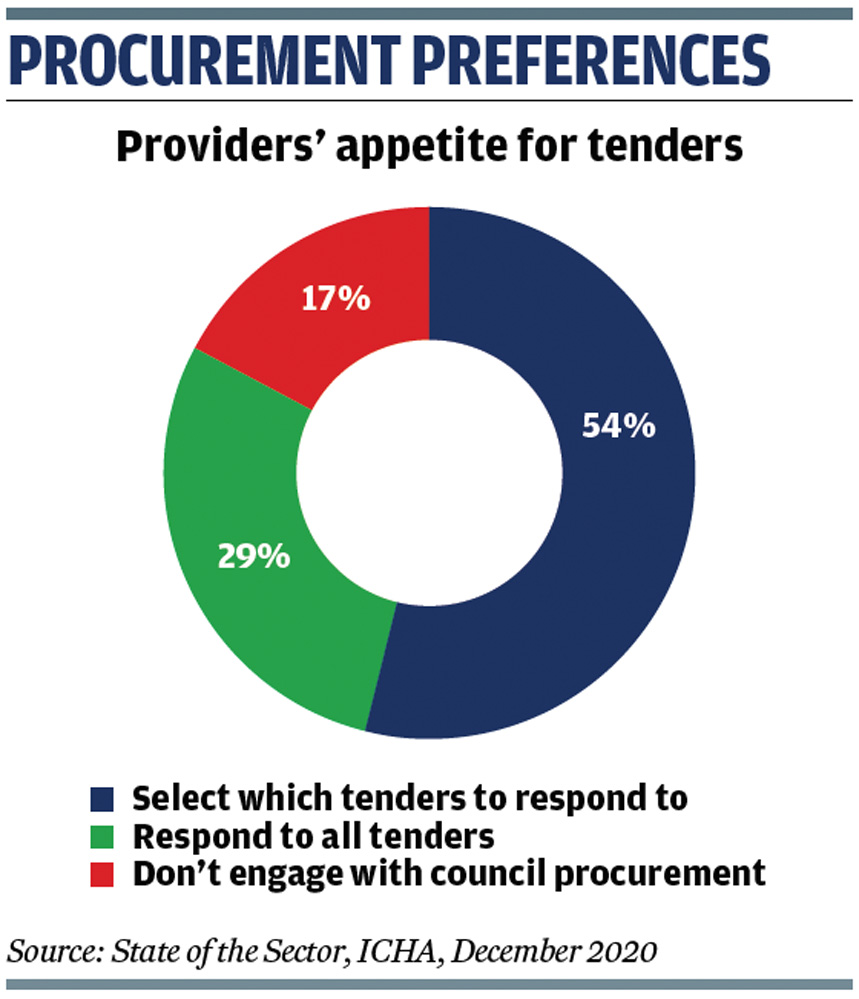

A radical rethink is required, replacing the current purchasing patterns with an approach focused around giving children and their families a better future not trying (and failing) to achieve a cheap price, with tailored, simpler, outcome-focused procurement documents. Currently, providers are increasingly choosing not to participate in existing procurements and agree placements outside these (see graphic).

Much of this is achievable within the PCR. Authorities should:

-

Offer a purchasing commitment either via a flexible block contract, a first refusal for vacancies with a commitment fee, or both.

-

Offer longer term contracts that support provider investment (capital and revenue including staff training), provide certainty of placement for the young people in care, support development of collaborative working and massively reduce the waste of time and resource on repeated procurement processes.

-

Radically change their procurement methodology and documents. Simpler, relevant, internally consistent and less adversarial documents focused around value, quality outcomes and fair contract terms are essential.

-

Acknowledge at political and senior level in local government that high-quality procurement will achieve better outcomes, value – including financial value – and should be invested in and developed. Perceiving procurement as a method of saving money is flawed.

Co-production

Implicit in this must be a recognition and acceptance by authorities and providers of each other's perspective through collaboration and co-production. Co-production should be the norm and this should be enshrined in pre-procurement consultation. Providers perceive there is last-minute lip service masquerading as “consultation” after key procurement terms are settled, a short timescale to respond and very limited or no change from authorities after their comments.

Pilots such as SESLIP are essential in demonstrating the value of a co-produced model which deliver innovative pilots keeping children local (see West Sussex practice example). This model can be replicable, but, at present, the problem is circular: until the benefit of better practice is seen its value will not be understood.

There is already good-quality partnership working including examples of block contracts for residential care that achieve impressive savings. However, these are achieved in spite – not because – of the public procurement regime and the procurement documents. Lip service may be paid to the law. If so, these are not models that can be rolled out more widely or which are too openly discussed.

7-point action plan

In the medium and longer term, I suggest the following changes:

-

A significant increase in the threshold at which any procurement regime applies and relying on authorities' internal procedures to achieve value for money. The threshold for works contracts is about £4.7m. Adopting this level would allow for more flexibility especially for fostering and one-off complex residential placements.

-

In parallel we need a radical examination of whether there ought to be a public procurement regime for children's services and if not, what should apply. The UK could revert to the pre-2015 or earlier models.

-

An acceptance that the future approach must apply to all services for children. The Department for Education already takes the view that the PCR does not apply to any external services for children with special educational needs and disabilities and yet many of these children have multiple problems, are in care and part of the overall care system. Education, care and health services must be joined within the same procurement model as other services for children with much more joined-up working.

-

New government guidance acknowledging that multi-authority large scale frameworks are not necessarily the best approach and should not be used as an attempt to drive down cost.

-

New government guidance requiring authorities to consider whether they ought to increase their in-house provision and providing financial support for building facilities. If authorities carry out the capital build and let a revenue only contract for service provision this would reduce the risk for providers and support much needed growth in the number of places. This model is used very successfully in other sectors, for example leisure centres, and avoids problems with capital and revenue contracts of lack of flexibility, unaffordable exit costs and the massive implementation costs exampled in PFI (private finance initiative) style contracts.

-

A change in approach and potentially governance model for commissioning and procurement supporting relatively small child-focused, collaborative pilot models with a better balance between spot and block purchases plus a single provider pre-qualification platform ideally via a national model. The latter will take time and meanwhile it could be implemented at regional level. There should be consideration of a more sophisticated partnership model (for example a local authority company).

-

A national matching register for vacancies incorporating an accreditation platform of basic services offered, Ofsted information, financial and other relevant information. This is a longer-term aspiration, requires government support and could be developed into more sophisticated pre-qualification, accreditation and procurement models with recommended models of good practice. However, at present there seems no DfE appetite for this. If it is introduced it is essential that this is via a fully co-produced approach rather than by central or local government paying lip service to provider involvement.

To conclude, radical change is needed; tinkering with the current approach will continue to fail children, local authorities and their partners.

Léonie Cowen is a solicitor and principal of Léonie Cowen & Associates. She specialises in providing legal and consultancy services to local authorities and their social enterprise partners including charities and other not-for-profit bodies in the social care and other sectors. She was a visiting lecturer at the University of Birmingham's post graduate Institute of Local Government Studies for many years, lecturing to social care commissioners throughout Great Britain and currently lectures to lawyers and commissioners on social care procurement throughout England and Wales. www.lcowen.co.uk/

Léonie Cowen is a solicitor and principal of Léonie Cowen & Associates. She specialises in providing legal and consultancy services to local authorities and their social enterprise partners including charities and other not-for-profit bodies in the social care and other sectors. She was a visiting lecturer at the University of Birmingham's post graduate Institute of Local Government Studies for many years, lecturing to social care commissioners throughout Great Britain and currently lectures to lawyers and commissioners on social care procurement throughout England and Wales. www.lcowen.co.uk/

Léonie Cowen is responding as an individual and the views expressed are wholly her own

FURTHER READING

- Green Paper: Transforming Public Procurement, Cabinet Office, Dec 2020

- High Needs Funding Arrangements, operational guidance, DfE, Sept 2020