Managing the costs of care

Jo Stephenson

Monday, May 14, 2012

Local authorities are increasingly joining forces to commission services for looked-after children. Jo Stephenson asks whether cutting costs will compromise the quality of care

The heaviest council budget cuts for a generation have coincided with an unprecedented rise in the number of children entering care. So it is not surprising that more and more local authorities are looking to work together to keep the costs of care placements down. This may have a positive impact on councils’ balance sheets, but the real question concerns the impact for the vulnerable children and young people in their care.

“In the current financial climate, local authorities are inevitably looking to cut costs,” says Wendy Banks, director of policy at the charity Voice, which promotes the rights of children in care and care leavers. “If they’re cutting management and commissioning costs then that’s what we want, rather than cuts to services for children. The main issue is to ensure children and young people’s needs are met.”

Combined buying power

The joint commissioning of services for looked-after children is still in its infancy, but several partnerships between authorities have sprung up. On the one hand, collaboration makes sense because together, councils can reduce back-office costs and use combined buying power to get better deals.

However, as Banks points out, the large-scale contracts risk squeezing out smaller, local care providers that have specialist expertise and experience in one area, such as dealing with separated children or working with a particular ethnic group. Support for children with the most complex needs may get lost in the mix. “Councils also need to think seriously about their role as a corporate parent,” Banks says. “If they’re one of a large group, then how closely are they parenting the children they’re responsible for?” Indeed, changing providers leads to significant upheaval for looked-after children who desperately want stability.

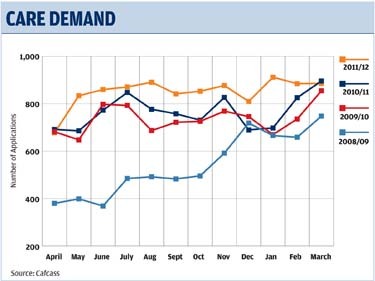

Yet councils are under immense strain, managing a 28 per cent cut in government funding over four years. Meanwhile, demand for care places stands at record levels. Between April 2011 and March 2012, the Children and Family Court Advisory and Support Service (Cafcass) received 10,199 new care applications, a 10.8 per cent rise on the previous financial year. The government has accepted the Family Justice Review’s recommendation for a six-month time limit for courts to deal with child protection cases, which will pile on the pressure.

However, those involved in new joint commissioning arrangements are adamant it is not just about money. Southampton City Council leads a partnership with 10 other councils to jointly commission independent fostering services. The contract, which took effect in April, saw 50 providers, previously contracted at an annual cost of up to £30m, slimmed down to 27. Southampton expects to save 7.4 per cent (£160,000) in the first year.

“Our number one priority was to improve outcomes,” says Southampton’s director of children’s services Clive Webster. “We expect to get better placements more quickly. Providers will increasingly understand the needs of participating authorities so they can tailor their offer and we’ll share data so they know what’s coming up. Therefore, we expect placements to be much more stable for children and young people, which is the key to good outcomes.”

Analysis of previous arrangements identified inconsistencies in councils’ contracts with providers, including variation in prices for very similar services. Crucially, the new partnership includes a “commitment to quality”. All providers must be rated “good” or better by Ofsted, explains Webster, who believes all 19 authorities in the South East of England will eventually join.

Collaborative benefits

Joint commissioning can have benefits for care providers as well as councils. It can reduce bureaucracy and duplication. Operating across larger areas means providers achieve economies of scale. Moreover, bigger, longer contracts offer greater certainty and reduced risk.

Andy Pallas, partnership and contracts manager at the fostering and adoption charity The Adolescent and Children’s Trust (Tact), says: “Our business has nearly doubled in four years. A significant proportion of that is from improved contracting arrangements with commissioning groups.” Of the 72 English local authorities with which Tact has contracts, 33 now work on a collaborative basis and have put out joint tenders for fostering services, compared to 17 in 2010 and five back in 2008. Placements commissioned by regional groupings increased from 44 in March 2010 to 214 in March 2012.

Pallas acknowledges that it is much easier for large organisations to respond to joint tenders although reduced bureaucracy can also help smaller providers. Having one tender process instead of several means much less paperwork and time spent on putting bids together for any organisation that wants to apply. This can benefit smaller providers who may not have dedicated staff to work on contracts and tenders.

Pallas adds that working across larger areas makes it easier to recruit foster carers and provide placements as soon as they are needed, which is better for children.

Proponents argue that joint commissioning also helps councils take a more strategic approach to care for “difficult-to-place” groups such as children with behavioural difficulties and sibling groups. Individually, they may have only small numbers of certain groups – for instance, teenagers – entering care, so placements have been arranged on an ad hoc basis. But by coming together, councils are dealing with a far greater number across a much larger area. This may, for example, highlight the need for a provider to commit to recruit and develop a team of specialist foster carers willing to take children aged 11 to 17.

On the down side, large-scale commissioning can “narrow the market” and lead to over-standardisation of the type of places on offer, with providers giving up on specialist provision because they are not being paid enough, warns Pallas. This might include care placements for children with severe disabilities or young people who have suffered extreme abuse and trauma.

The West London Alliance is helping nine councils identify efficiencies across children’s services, including developing joint commissioning of independent fostering agencies. The alliance includes Barnet, Brent, Ealing, Harrow, Hillingdon and Hounslow. In 2010, the boroughs involved used 88 different providers to buy 1,118 placements at a cost of £30m. The project will lead to the councils procuring placements via a framework contract by January 2013, which will deliver estimated savings of between £750,000 and £2m.

On children’s homes they are analysing historic, present and future needs, and will draw up a business case for sub-regional commissioning of residential beds. But Matt Jones, assistant director for the West London Alliance’s social care efficiencies unit, says: “It doesn’t really matter what you’re buying, if you’re buying solely on price then it is a false economy. Take that approach to care provision and you’ll get increased placement breakdown, a lack of investment in staff, skills and facilities, and providers going bust.”

However, he believes there is a common “myth” that when it comes to care expensive generally means better. “You can get very good services with good outcomes that are also good value for money,” he says. “My experience is good providers are generally good all round – they’re on top of their budgets, less wasteful and manage things well.”

Darren Johnson, operational director for children’s services at the charity Action for Children, believes “intelligent commissioning” relies on councils involving providers before tenders are drawn up. That way, commissioners achieve stronger partnerships and benefit from the expertise and innovation found in charities.

“Voluntary sector organisations large and small also need to look at how they can come together to help each other locally and regionally,” says Johnson. Both large and small providers can benefit from sharing back-office functions, pooling budgets and sharing expertise.

Intelligent commissioning

Three London councils are among those who have gone furthest down the joint commissioning route. Hammersmith and Fulham, Westminster and Kensington & Chelsea have merged the majority of their children’s services. An overarching commissioning directorate oversees arrangements with external providers including adoption and fostering services and supported accommodation for care leavers.

Andrew Christie, tri-borough director of children’s services, admits one of the main drivers was to cut costs but he firmly believes working together is better for children.

“For example, we get more flexible use of our foster carers, which means we’re much more likely to get better matches for children,” he says. The tri-borough arrangement also means the very best practice is shared. “There are examples of best practice in all three. We haven’t simply got one borough that’s outstanding. Every authority will have a different pattern of services.”

If councils can work through such differences then joining forces means “more effective services and better outcomes”, he says.

But he adds: “When you’re operating on 28 per cent less budget then in some ways maintaining existing standards is a good result. Although we’re far more ambitious than that.”

Council collaborations

North West

Twenty-two councils in the North West are members of Placements Northwest, established to help make out-of-authority placements in residential care, independent fostering, education and leaving care provision. The project manages information about providers across the region and benchmarks costs and performance for all councils. A North West Foster Care Contract enables councils to buy external foster placements with set specifications. It is now working on minimum standards for leaving care services and a regional contract framework for residential and leaving care tenders.

West Midlands

The West Midlands Children’s Commissioning Partnership has focused to date on looked-after children but it is moving into other areas including special educational needs provision. Regional contracts are in place for fostering, residential care and independent special schools. The partnership runs a placement database and has developed a regional process for reviewing prices across providers.

South West

Five authorities in the South West peninsula region – Cornwall, Plymouth, Torbay, Devon and Somerset– have joined forces to improve commissioning, including establishing a central purchasing body for foster and residential places in the independent sector. “Pre-qualified” providers must meet minimum quality standards and offer value for money.