Early Help Special Report Policy Context

Derren Hayes

Tuesday, August 30, 2022

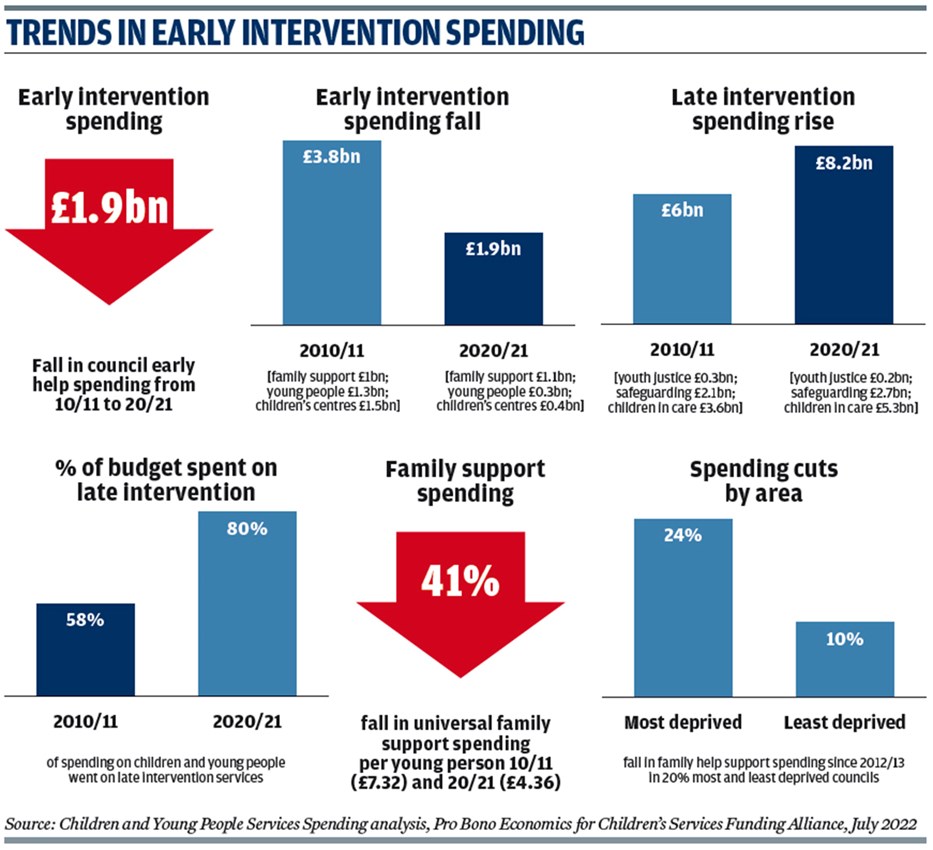

Since 2010/11, spending by councils on early help services has fallen from £3.8bn to £1.9bn per year (see graphics). The brunt of the spending cuts has been on support for young people – 77 per cent fall from £1.3bn to £300m – and children’s centres – down 73 per cent from £1.5bn to £400m.

Over the same period, spending on late interventions has risen by £2.2bn to total £8.2bn by 2020/21. Provisional figures suggest this will grow beyond £8.5bn in 2021/22 and some sector experts project it will be £10bn by 2025. The bulk of the increase is on children in care, for which the total bill has grown 47 per cent to £5.3bn in 2020/21.

Analysis by Pro Bono Economics for the Children’s Services Funding Alliance coalition of children’s charities published in July, shows the gap between the amounts councils spend on late and early interventions has grown from a 60/40 split in 2010/11 to 80/20 by 2020/21. The shift is mainly due to the £2bn cut in the early intervention grant that government gives to local authorities, and as early help services are not statutory they are most vulnerable to being cut when budgets are tight.

The report sets out the negative impact this scenario is having on councils’ ability to deliver effective services.

“As local authorities are forced to prioritise crisis interventions at the expense of early intervention, need for crisis services increases,” it states.

“Early interventions often help young people and their families cope better with difficult situations. If these are no longer available, then difficulties can escalate – meaning that more families are likely to reach crisis point.

“There is growing empirical evidence that those local authorities that experience the biggest reductions in children’s services spending tend to see more children aged 16 to 17 entering care, as well as more children being formally identified as in need.”

While the amount spent on family support has risen slightly over the decade, the analysis shows how this is largely focused on interventions targeted at struggling families. Total spending on “universal family support” – which is open to all and may include children from disadvantaged groups – decreased by £50m. The result is a cut of £2.96 per young person (aged 0 to 25), from £7.32 in 2010/11 to £4.36 in 2020/21 – a 41 per cent drop.

To compound matters, the most deprived local authorities, which tend to have higher levels of looked-after children and greatest support need, have seen deeper cuts to early help spending than more affluent areas.

The alliance says a “radical reset” of the system is urgently needed to stop the situation deteriorating further. While system reform is a key part of that equation, so too is significantly extra funding from government.

Care Review reforms

The Care Review, led by former Frontline chief executive Josh MacAlister, took 15 months to complete. The government has pledged to implement the 80 recommendations and has established a board to set out later this year how it will go about doing this.

MacAlister says that creating a social care system that has early help at its core would see 17,000 children who would have come into care over the next decade remain with their families saving £517m in local authority care costs.

A new definition of family help underpins MacAlister’s plans for supporting families, which are estimated to cost £2bn to implement over the next five years.

“Family help should be built in partnership with the families and communities it serves,” the review states. “It should start from the mindset that all families may need help at times, whilst also being equipped to recognise when children might be at risk of significant harm.”

Family help should be delivered by “skilled professionals” across a multidisciplinary team with a focus on building trusting relationships when “mechanical referrals and assessments are replaced with tailored conversations”.

This approach aims to merge targeted early help work and work carried out under section 17 of the Children Act 1989, which places a general duty on all local authorities to safeguard and promote the welfare of children, under what the review terms “family help”.

This is designed to “reclaim the original intention of the Children Act 1989 and provide children and families with the support they need, keeping more families together and helping children to thrive”, according to the review.

New approaches

To deliver these changes, MacAlister proposes the creation of family help teams working in geographical areas serving up to 300,000 residents. Social workers would work alongside multidisciplinary teams made up of professionals such as family support workers, domestic abuse workers and mental health practitioners.

Each family would be assigned a key worker, although in a shift from current practice, this would not necessarily be a social worker. Instead, it would depend on a family’s individual needs, the review states.

Family help teams would be overseen by local authority children’s services but would work from community buildings such as schools and new family hubs.

“At its most basic, providing multidisciplinary, non-stigmatising support should bring positive change to families and free up social work capacity to identify the small number of cases where children continue to be at risk of harm,” according to the review.

Ray Jones, emeritus professor of social work at Kingston University, says work around embedding family help teams in “stigma-free” environments is a “sensible way forward”.

The review “has not shied away from the challenge, addressing knotty issues like multi-agency working”, adds chief executive of the National Children’s Bureau Anna Feutchwang.

The review also urges the government to pilot the devolution of power to neighbourhoods through what MacAlister calls “radical” family help practices. This would involve a director of children’s services delegating operational responsibility for individual geographic areas to a family help director “with their own budget, delegated decision making and the freedom to work with communities from the ground up to design and build services” with oversight from the local authority and Ofsted.

The Children’s Services Funding Alliance report says the review recommendations offer a costed model for shifting the system in the right direction. “That model prioritises supporting families, working early to prevent crisis from arising in the first place, and ultimately moving towards a more caring system for our vulnerable children and young people,” it states.

However, it says “a dedicated ringfenced grant” would help lock in the gains reaped from the initial investment and “ensure that expenditure on early intervention services is protected from the day-to-day pressures of crisis management”.

Other policy reforms

At last year’s Spending Review, the government announced £82m to establish family hubs in 75 local authorities over the next three years. The funding is in addition to the £34m previously announced to set up hubs in 12 pilot areas, create a national centre to co-ordinate practice and develop approaches to digital support.

Family hubs across England will aim to ensure that all families have access to high quality services and supportive relationships within their local area. They will be designed to provide family help early, when it is needed – from pregnancy, through the child’s youngest years and later childhood, and into adolescence until they reach the age of 24.

Hubs that provide a wide range of services for parents and older children – as opposed to the 0-5 focus offered by children’s centres – are not a new concept: some councils have already moved to a hub model in response to early help budget cuts since 2010.

Early years providers and local authorities are questioning what this means for the more than 2,500 children’s centres still being provided by councils. Last year, former children’s minister Will Quince told the public services committee that it is his “ambition” for all councils move to the family hubs model.

The Anna Freud Centre has been appointed to lead the National Centre for Family Hubs, a new learning network funded by the Department for Education, to champion family hubs and spread best practice on evidence-based service models across England.

Westminster Council was one of the early adopters of family hubs and says they have been crucial to reducing exclusions and re-referrals of families in need (see practice example).

The government’s Troubled Families programme has been refreshed under the new name Supporting Families a decade after it was first launched.

More than £1.5bn has been ploughed into the programme since its creation following the 2011 riots, with government analysis showing it supported more than 500,000 families over a decade with issues like generational joblessness, anti-social behaviour and school truanting.

The Troubled Families programme operated as two distinct tranches running from 2012 to 2015 and 2015 to 2021. The first phase of the scheme aimed to “turn around” 120,000 families in England. Government figures state 116,654 of the 117,000 identified families had achieved this outcome by May 2015.

Announcing the name change to Supporting Families, the government says this is to “reflect what it does in principle and in practice”. The government has pledged £695m in Supporting Families until March 2025 and aims to help 300,000 families over the next three years.

A revamp of the scheme for 2022-25, published in the spring, expands the programme’s six headline criteria to include 10 outcomes to measure specific challenges facing families, such as preventing domestic violence, child abuse and exploitation.

These come into effect from October 2022 and cover: getting a good education, good early years development, improved mental and physical health, promoting recovery and reducing substance abuse, improved family relationships, protecting children from abuse and exploitation, preventing crime, protecting families from domestic abuse, secure housing, and financial stability.

Local schemes such as Manchester Youth Zone’s Junior Choices highlight the vital role youth workers can play in diverting vulnerable young people at risk of exploitation through intensive support (see practice example).

Another notable scheme is A Better Start, a £215m National Lottery funded programme focused on promoting good early childhood development. The programme funds local partnerships in five areas across England to test new ways of making support and services for families stronger so that children can have the best start to life. Now, seven years into its 10-year lifespan, the scheme is delivering significant improvements (see below).

Schemes like A Better Start are proving vital for developing new approaches to early intervention, but children’s services leaders say implementing the Care Review measures must be a priority for the new Prime Minister when they take office (see ADCS view below). Without that, it will be an uphill battle to rebalance children’s services towards early help.

A Better Start sites build strong foundations for children

A Better Start (ABS) is the 10-year, £215m programme set-up by The National Lottery Community Fund (NLCF) and supported by the National Children’s Bureau, which is designing and delivering a programme of shared learning and development support.

The five ABS partnerships, launched in 2015, are supporting families to give their babies and very young children the best possible start in life and are already delivering benefits, some of which are summarised below.

Diet and nutrition: Better Start Bradford

‘Cooking for a Better Start’ is delivered through six weekly, practical sessions where parents learn to prepare healthy, low-cost meals for their families. The project is a universal service for all families with children aged 0-3 and aims to improve the family’s knowledge of healthy meals and increase their confidence in preparing them. The project also helps engage parents in the wider range of Better Start Bradford projects. Following the cooking sessions, parents report increased skills and knowledge, for example on estimating healthy portion sizes and in interpreting food labelling and feeling more confident to make healthy choices.

Social and emotional skills: Small Steps, Big Changes, Nottingham

The Family Mentor service is a paid peer workforce, co-produced with local families. A key element of the service is the delivery of Small Steps at Home, a manualised programme of evidence-informed interventions designed to support childhood development. The responsive visits begin antenatally, occur weekly until the infant is six months, and then monthly. After they turn two, a monthly telephone rather than face-to-face visit is offered.

Between 2015 and 2020, 1,916 children were enrolled in the programme. An evaluation found the programme to be an effective model for parents facing multiple challenges.

Language and communication skills: Blackpool Better Start

Through a “no wrong door” policy, Blackpool Better Start aims to identify speech, language and communication needs (SLC) in children early, and support parents and carers to address these by accessing the services they need. Training is provided for all health visitors to use the WellComm Assessment, a speech and language toolkit for screening and intervention in the early years. All children in Blackpool are now offered screening at 9-12 months, 24 months and 36-month checks. Children with SLC needs are now being identified and referred for support earlier, which has increased referrals to NHS speech therapy services.

Place-based system change: Lambeth Early Action Partnership

To effect place-based systems change, Lambeth Early Action Partnership (LEAP) is developing a shared measurement system to track progress towards LEAP’s shared impact and outcomes; both in individual services and as a collective impact initiative. Work has: improved understanding of how services and initiatives are working together to achieve shared outcomes, encouraged more collaborative working and informed commissioning decisions. A shared measurement system, captured on an integrated data platform, will be invaluable for Lambeth and local organisations, which will support them to pool data and effectively monitor the progress of collaborative work towards outcomes.

Parent and community led services: A Better Start Southend

A Better Start Southend (ABSS) commissions the Southend Association for Voluntary Service to deliver engagement activities including the recruitment and training of Parent Champions and Parent Ambassadors. As part of the programme, parents are able to bid individually or in groups for small amounts of funding to deliver local engagement activities. All approved activities are led and delivered by Parent Champions working with ABSS partners to build community capacity. One such community-led project to improve a local park has developed into a charity to improve the quality and accessibility of outdoor public spaces.

-

A Better Start: Five years of learning from NCB and NLCF www.ncb.org.uk/sites/default/files/uploads/attachments/ABS-5-Year-learning.pdf

ADCS VIEW

Investing in early help makes fiscal and moral sense

By John Pearce is ADCS vice president 2022/23

Amid the Conservative leadership contest, it feels important to repeat the need for long-term investment in early help and prevention services for children and families.

There is no doubt that the earlier we work with children and families to help them overcome the issues they face, the less impact these challenges will have on their lives and on society. The Early Intervention Foundation estimates billions of pounds are spent by public sector agencies on late intervention every year, yet the human cost of late intervention is much greater.

Local authorities are committed to supporting children and families at the earliest possible opportunity before they reach crisis point, and good work is happening up and down the country, however, there is currently not enough funding in the system to enable this approach in all local authorities. Funding for early intervention should be long term, sustainable and equitable and not based on the quality of a bid.

Analysis by a coalition of children’s charities reveals deep cuts to early intervention services while demand for children’s services is increasing. Local authorities must spend on statutory child protection services where need exists. This means tough decisions must be made about the very services that tackle the root causes of the issues families face, like children’s centres and family support, services that also reduce future demand. We are now seeing the impact on statutory services of short-term decisions councils were forced to make during austerity. This is a false economy and not in the best interests of children and families.

The previous Spending Review gave us greater clarity until 2025 around vital funding for the Supporting Families programme which is increasingly central to the early help offer in a growing number of local authorities. Similarly, recent investment in family hubs is a step in the right direction, but we need long-term solutions to ensure all children and families can benefit from earlier support when they need it. And we need to ensure family hubs don’t become everything to everyone, diluting the impact they could have.

The new Prime Minister will have many competing priorities but investing in children must be at the top. Investing in earlier intervention to support children and families is not only the right thing to do – as is reducing, and ultimately ending, child poverty in this country, a key driver of demand for children’s social care – it represents smart fiscal policy. Parenting is much harder to do when you are worried about how you are going to feed and keep your children warm and in the coming months more families will be facing significant financial pressures.

The Independent Review of Children’s Social Care provides an opportunity to shift the dial on how and when we spend on children and families and gives an indication of how much is needed to reset the system. We stand ready to work with the new government to put children first.