Early Childhood Development: Policy context

Derren Hayes

Tuesday, May 29, 2018

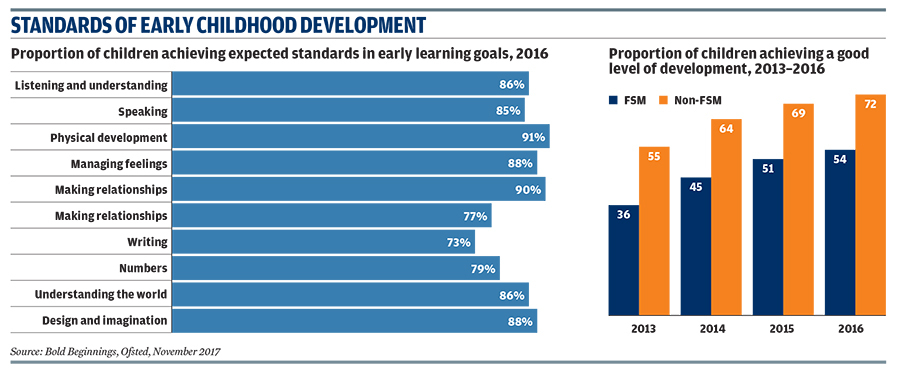

Bold Beginnings, the Ofsted report published in November 2017, highlighted the progress early education services have made in ensuring young children develop the basic skills they need to learn and thrive.

Between 2013 and 2016, the proportion of five-year-olds that have a "good" level of development has risen from 36 to 54 per cent for children in receipt of free school meals and from 55 to 72 per cent for their better off peers (see graphics).

However, the report criticises some schools and teaching professionals for not being sufficiently ambitious enough for children, and says more must be done to support disadvantaged pupils to develop at a faster pace. Narrowing the attainment gap at the start of formal education - currently standing at around 18 months - is vital to improve the life chances of poorer children, it adds.

The policy response has seen the government develop a number of universal and targeted initiatives aimed at improving access to high-quality early years provision. It has introduced 15 hours of early education for disadvantaged two-year-olds, 30 hours free childcare for three and four-year-olds, the creation of tax-free childcare and rebates on the cost of childcare for universal credit claimants.

At a recent parliamentary hearing, children's minister Nadhim Zahawi said the government's prioritisng of free childcare represented a "shift" from investing in "bricks and mortar" in the form of children's centres "to direct intervention to the individual child". A Sutton Trust study earlier this year concluded that around a third of all children's centres have either closed completely or lost services since 2010. However, Zahawi claimed that the most deprived areas have not excperienced closures.

A number of the government's social mobility programmes also focus on improving outcomes for young children in the most deprived communities. The 12 initial Social Mobility Opportunity Areas are piloting new ways of supporting schools and early years providers to improve early childhood development, all of which have the overarching aim of closing the developmental and "word gap".

The government has also recently launched a programme for local authorities to carry out peer reviews on one another to identify ways to enhance the early language and literacy skills of the poorest children (see Bishop Alexander practice example).

Meanwhile, the Big Lottery Fund is investing £215m in its Better Start programme, which aims to test new approaches to promoting good early childhood development. Launched in 2015, the initiative has seen the creation of multi-provider partnerships in five areas, including Blackpool (see practice example).

While much of the policy focus is on narrowing the attainment gap, there are increasing concerns about the impact that poor diet is having on young children's physical development. Around a quarter of children in England are obese or overweight by the time they start reception, prompting councils to develop healthy food programmes to support parents in disadvantaged areas (see Rose food vouchers practice example). A host of parenting support programmes, including the Family Nurse Partnership and Incredible Years are also helping improve parenting skills and outcomes for young children (see research evidence).

There is also a wider debate taking place about what good childhood development entails, with the government recently publishing plans to introduce a "baseline assessment" of pupils' abilities in reception from next year. Early years groups and teachers unions are concerned the move would increase the focus on academic skills at the expense of play-based learning in the Early Years Foundation Stage framework.

Here, five experts outline key emerging issues affecting early childhood development.

PARENTING INPUT

By Kirsten Asmussen, head of what works, child development, Early Intervention Foundation

Evidence summarised in our forthcoming report on key competencies in children's cognitive development highlights how programmes can help parents talk to their children in a way that supports their language development. Here are the key messages.

Quality over quantity

It is not just about words. While language disparities have traditionally been described in terms of a ‘word gap', evidence tells us it is not about quantity, but quality. Specifically, it is about the quality of the child-directed speech that parents use on a day-to-day basis. Child-directed speech is an exaggerated form of adult speech that involves a wider range of vocal tones, a slower rate and shorter phrases. Studies suggest this helps children understand the importance of language for communication. By comparison, words heard through normal adult speech or television provide relatively little value for children's early language learning.

Learning by conversation

Studies show, however, that during the early years, language is best supported through developmentally appropriate parent-child conversations linked to the child's interests.

- During infancy, babies benefit from child-directed speech during joint attention activities involving household items and toys.

- During toddlerhood, quantity is crucial, particularly in terms of new vocabulary.

- During the third year, children benefit from more diverse and grammatically complex language that reflects their interests.

- During the fourth and fifth years, children benefit from participating in conversations that make use of structured narratives.

Content counts

In this respect, parent-child conversations support children's cognitive development in a variety of other important ways:

- Conversations about objects and living things supports children's analogical reasoning capabilities.

- Conversations about the thoughts, feelings and desires of others also increases empathy.

- Parent-child "number talk" has been found to support children's early counting capabilities.

Dosage matters

The best evidence also tells us that parents need to hear these messages more than once in order to remember and act on them. Our report recommends how these messages can be shared through a well co-ordinated early years' offer, involving health visitors, children's centres, childcare and pre-school.

PHYSICAL AND MENTAL HEALTH

By Max Davie, health promotion officer, Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health

Public Health England figures show that 22.2 per cent of children are overweight and 9.3 per cent obese by the time they enter reception. The soft drinks industry Levy and up-coming childhood obesity strategy are steps in the right direction to tackling this. What is important now is that the "sugar tax" is properly evaluated and that the government's childhood obesity strategy includes measures that ensure:

There are sufficient numbers of health visitors to support new parents make healthy choices.

Baby foods meet nutritional standards as we know tastes develop early

There are restrictions on junk food advertising before 9pm and measures are explored for protecting children from these adverts online.

We also know that poor dental health and obesity often go hand-in-hand so more must be done to encourage parents to take their child to see a dentist before their 1st birthday.

Children need a combination of nutrition and exercise to maintain healthy lifestyles, and if we get this right, they're much more likely to become healthy adults.

Sometimes finding safe places to exercise are a challenge which is why the college would like the government to implement 20mph zones in built-up areas, encouraging more children to play outdoors.

We'd also like to see a ban on smoking in public places - children should not be subjected to the dangers of second-hand-smoke in playgrounds.

Air pollution is an invisible threat to children and no more so than for those living in inner-cities. Clean air zones are an excellent way of reducing pollution so rolling similar schemes out across urban centres will improve child health. They also promote active infrastructure - pedestrian zones and cycle lanes for example, making it easier for children to be active. To compliment this, air pollution must be monitored by central and local government, tracking exposure to harmful pollutants in major urban areas and near schools.

The burden of ill health places huge demand on services. Conditions associated with obesity cost the NHS in excess of £5bn a year and, if left unaddressed, it poses a substantial threat to healthcare services.

CHILD POVERTY

By Naomi Eisenstadt, senior research fellow, University of Oxford

Set up by the Labour government in 1999, Sure Start was originally targeted at disadvantaged areas. Sure Start services proved so popular that the government expanded the programme so that there would be a children's centre in all areas, a target of 3,500 in all by 2010. The centres were meant to provide early education and care, support for parents, health advice and employment advice. A national evaluation by the University of Oxford in 2015 found positive effects, particularly for those families who used the centres regularly. It was encouraging to find that low income families were found to particularly benefit.

The Sutton Trust recently commissioned a team at Oxford University to conduct a survey of existing children's centres to find out how many had closed. Its report found that up to 30 per cent of centres had closed, with many providing limited services on certain days of the week.

Benefit changes

Benefits changes have also put considerable strain on families with young children. The benefits cap, the two child limit on tax credits, and the increasing use of sanctions, including periodic reductions of cash benefits, are all resulting in increases in child poverty.

The combination of cuts to children and families services, along with reductions in income transfers, has created a perfect storm, felt most acutely by families with children under five, who are over represented in poverty figures.

Local authorities are at a loss, having to concentrate their reducing budgets on those most in need with highly complex problems that are inordinately expensive to solve.

Early intervention has been rebadged as early help; largely about keeping children out of care. The edge of care already indicates a family has severe difficulties rather than the larger group of families for whom a little help at the right time through the low cost support of children's centres, could have made a difference.

The government's outrage at stalled social mobility is meaningless when families are faced with rising pressures and decreasing support.

PLAY-BASED LEARNING

By Beatrice Merrick, chief executive, Early Education

The government's proposals to review the early learning goals (ELGs) is a cause of concern. The review - arising from the Review of Primary Assessment not from any kind of review of the Early Years Foundation Stage (EYFS) itself - has not yet been subject to a broad and open consultation with the early years sector that would enable an informed assessment as to whether the ELGs need review, and how they need to change. The drive for change appears to be a desire to "align" the Reception year with the Year 1 curriculum, and not the other way round.

Despite the central place of learning through play in the EYFS, Ofsted's Bold Beginnings report seemed to be advocating overly formal and teacher-led approaches in the Reception year, based on very limited and anecdotal evidence. There has been a sense that policy relating to the EYFS is being driven by top-down pressures, not sound understanding of the latest evidence-informed early years practice.

The government's new focus on the "word gap" shows that policymakers are engaging with current research, although something seems to have got lost in translation. Unfortunately, documents such as Bold Beginnings suggest schools tackle the word gap by ensuring children are read to more by their teachers, rather than through dialogue and enriching experiences.

There is extensive evidence about what works in the early years, and the EYFS draws heavily on the research evidence for this: children need enabling environments indoors and out, skilled and knowledgeable adults who respond positively to their needs and interests and who foster and extend their learning. Young children need to be active, engaging with varied, challenging, playful experiences.

CLOSING THE WORD GAP

By June O'Sullivan, chief executive, London Early Years Foundation

The 30 Million Word Gap report from Hart and Risley (2003) found that the language heard by poorer children compared with their more privileged peers could amount to a gap of 30 million words by the time the children had reached three years. That gap was difficult to close, leaving children from the same socio-economic background two years behind their peers at GCSE level.

Bernstein's (1973) found that children who have a grasp of formal language, rather than being restricted to informal language, were at an enormous advantage in the education system. This was, in effect, the distinction between the "restricted code" which is accessible to both the working and the middle class and the "elaborated code" which belongs to the educated classes, and which has a flexibility that facilitates the expression of analytical and abstract ideas and arguments. In other words, enriched language, correctly constructed could help reduce the educational achievement gap.

Great dialogue and conversations matter. A good conversation will include context, nuance, explanation, information, narration, coaxing, suggestions, encouragement, demonstration assistance and warmth.

The importance of oracy should never be forgotten even in the rush to phonics and early reading. Staff need to read books rich with rhyme, rhythm and alliteration but most importantly talk about the books to ensure contextual understanding.

We require our staff to wallow in luscious language, extend conversations and use many different ways of describing regular things in the nursery. If you can say "nice" you can say, "beautiful", "wonderful", "glorious", "pleasant" and "delightful". The message is clear, language is central to teaching in the early years but it needs to be rich, warm, relevant and build literacy bridges into the home.

ADCS VIEW

Make better use of childcare funding

By Stuart Gallimore, director of children's service, East Sussex and ADCS president

Our childhood experiences shape the people we become in later life and the importance of the first three or four years cannot be understated in development terms. Growing up in a household experiencing material hardship brings increased exposure to risk factors -the stresses and strains of a low or unstable income and poor-quality housing are just some of the challenges families are contending with. Babies born into poverty are more likely to have a low birth weight and by the age of three, poorer children are on average nine months behind in development terms than their wealthier peers.

The Department for Education's investment in 30 hours "free" childcare, is set to rise to a staggering £6bn per year by 2020. However, the shortfall between the hourly rate offered and actual costs jeopardises quality, and there are growing concerns about the eligibility criteria - as it stands, this policy offers a couple with an annual income up to £199,000 more help than a lone parent working full-time on a zero hours contract. The findings of a recent survey by head teacher union NAHT raised concerns that children from the most disadvantaged backgrounds are not benefitting from this policy.

At a time when social mobility is a government priority, the focus on broadening access to childcare rather than developing high quality early education seems a false economy. Most children live in their families and thrive; for some, a little extra early support in the early years is transformative.

The funding formula that underpins free childcare doesn't recognise the higher running costs associated with nursery schools because they employ specialist teachers, it also overlooks the benefits of this provision - they help close the attainment gap more effectively than any other part of the education system.

In these times of rising inequality and falling investment in public services, it is more important than ever that we spend our money wisely. That means available funding is targeted towards the most socially and economically disadvantaged in a bid to break the cycle. We know that the greatest opportunity to make a tangible difference to children's prospects occurs when they are very young. Imagine how many children's centres or nursery schools we could retain or reinstate with £6bn. Or how much more productive our economy would be in 20 or 30 years if we invested not just the bare minimum in our children's future, but enough to make it the very best in the world.

FURTHER READING

- Reception baseline assessment, DfE, April 2018

- Unlocking Talent, Fulfilling Potential, DfE, December 2017

- Bold Beginnings, Ofsted, November 2017

- Early Years Foundation Stage framework, DfE, March 2017

- Good practice in early education, SEED project, DfE, January 2017

This article is part of CYP Now's special report on early childhood development. Click here for more