Youth Work Impact: Policy context

Derren Hayes

Tuesday, July 31, 2018

Supply and demand issues around funding have been crucial in the development of a youth work "impact agenda". In 2017/18, local authorities expected to spend 50 per cent less on young people's services than at the start of the decade as a result of reduced government funding for non-statutory early help provision (see ADCS view).

Concurrently, a new set of funders have entered the market to fund voluntary sector youth work projects, from big multi-nationals to social finance investors. This has been underpinned by a number of policy papers and associated government programmes that incorporate payment-by-results (PbR) mechanisms as a requirement for receiving money.

For example, the £80m Life Chances Fund, £16m Youth Engagement Fund, and the Department for Work and Pensions Innovation Fund had funding linked to projects achieving targets to demonstrate their impact. Inherent in the PbR model is the need to monitor activities and meet certain outcomes criteria set by the funders. Some argue that this has led to a narrow way of measuring impact, one that prioritises number-crunching.

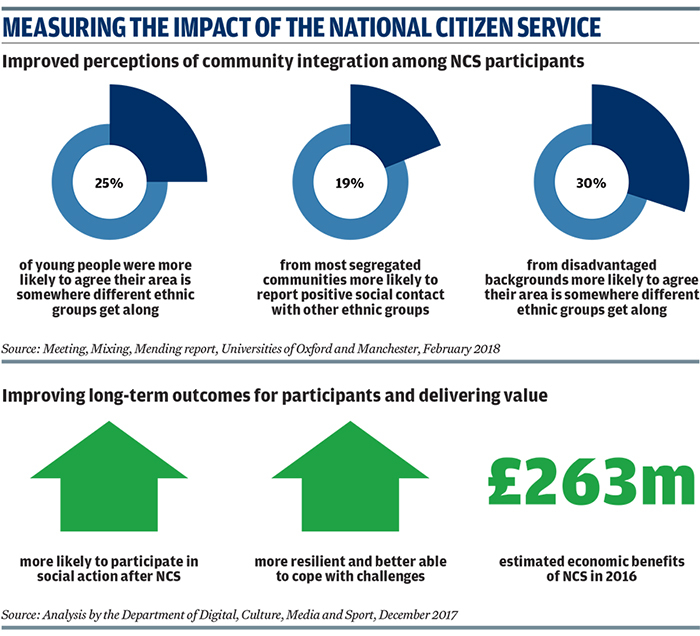

To help establish best practice in measuring outcomes, youth groups and the government backed the establishment of the Centre for Youth Impact in 2014. It has presented approaches that recognise the need to gather qualitative as well as quantitative data when measuring the impact that youth services have on young people's life outcomes. The National Citizen Service (NCS), the government-backed youth social action programme, has adopted this mixed approach. It collects data on the impact the scheme has on participant wellbeing, as well as the estimated economic benefits (see below).

The development of the impact agenda has seen a rise in the amount of evidence being developed on the "value" of youth work (see research evidence). While the pressure on council services shows no signs of abating, increasing numbers of youth workers are being employed by agencies working with vulnerable young people, from those with long-term health conditions and disabilities to gang members in youth justice settings (see practice examples). All recognise the contribution that youth workers make to improving young people's outcomes.

With evidenced-based youth services set to be a key element of the upcoming Civil Society Strategy, here, four experts outline key trends in the development of youth work impact.?

Refine understanding of impact

By Bethia McNeil, director, Centre for Youth Impact

The issue of impact in youth work and services for young people is a contentious one. There are some who would argue that, had the youth sector done more to evidence its impact in the past, youth services (and youth work particularly) would have been better protected amid the ongoing devastating budget cuts. Others will argue that there is copious existing evidence of the impact of youth work and youth services, but that it has been overlooked or even wilfully ignored by funders and policymakers. It is certainly true that evidence and impact continue to be a topic of debate in the sector. So, where should we all search for answers?

My suggestion is that we shouldn't focus our search on definitive answers, but on actionable insights. The evidence and impact debate has become increasingly fraught, and common responses are often more about defensiveness and closing down debate, rather than looking for new understanding. Will we ever "prove" the impact of youth work? Unlikely; we lack the collective agreement within and beyond the sector about what it means to "prove" or, indeed, how this might be achieved. Could we do more to gather shared insights that help us learn, improve and adapt to the needs and wants of young people? Certainly; but we'll need a collective shift in thinking and behaviour to get there. This doesn't mean turning away wholesale from the "what works" agenda: we have much to learn from debates about "standards" of evidence.

However, this approach has real limitations when it comes to youth work and services for young people. It favours structured interventions with predefined outcomes; it does not focus sufficiently on context or quality implementation; it can be costly and burdensome for providers, with the direction generally set by funders and policy; and the search for higher standards of evidence for youth work impact remain elusive - with very good reason. Fundamentally, our argument is that we need a more progressive approach to evidence of impact than is represented by a binary set of standards.

At a time when government is preparing a new Civil Society Strategy, we are likely to be hearing more about the value of listening and responding to communities, of consistent and trusting relationships, and of long-term investment in building personal and shared assets. A strong civil society supports people and communities to achieve meaningful change on their own terms. This is what youth work and services for young people are all about. So what does this mean for how we understand impact?

First, it means we need to better understand the role that youth work and services for young people play within broader systems of support, and in young people's lives. This will mean valuing consistent, developmental relationships alongside long-term outcomes. Second, it means we need to focus more on the connection between quality (what we do and how we do it) and outcomes (what happens as a result). Third, a better understanding of quality would mean a shift in emphasis from often costly and burdensome external evaluation towards continuous, light touch, embedded improvement efforts.

It is the role of government and the funding community to work alongside the sector to make this a reality - neither could or should achieve this shift alone. Incentives need to be better aligned, workforce development needs to support reflection and improvement, and a broader notion of evidence needs to be embraced.

Quality practitioners crucial to good impact

By Adam Muirhead, chair, Institute for Youth Work

The Institute for Youth Work (IYW) was primarily established to support the sector to reach the highest possible standards for youth work. It has become clear that in the current economic and political climate conversations about quality are now closely linked to those of impact measurement and, therefore, we have had to take stock of this shift in paradigm.

To increase standards (and supposed impact) has meant a few different things for the IYW's work plan. We have been closely looking at the professionalisation agenda for youth work and what it would mean in practice. While becoming more professionalised may increase standards - and impact - across the board, professionalism in youth work is complicated. There are still many people who are wary of what may become increased top-down regulation and the potential isolation of volunteers, who still make up a substantial part of our workforce. The other consideration is that to be "more professional" for other groups of workers often implies conformity and more "out-of-the-box" solutions to working problems; would professionalisation challenge our young person-centred methodologies and remove scope for innovation?

We have resolved to do the work to raise professional standards while being supportive of the rich diversity of ways that youth work is practiced. This has seen us lead on the development of a voluntary register for youth workers that would allow them to demonstrate their ongoing commitment to continued professional development. It would also allow employers to see who is registered, what qualification they have and would allow government to see exactly what the youth workforce looks like in England.

The register - details of which will be announced soon - would need to be clearly linked to professional qualification in youth work from a course validated by the Education and Training Standards Committee, hosted by the National Youth Agency. Protecting the link between professional qualification and the agreed terms and conditions for professionally qualified youth workers (set by the Joint Negotiating Committee) is key to ensuring that high quality, impactful practitioners are valued.

Training providers need to continually evolve to meet the ever-changing youth work climate in terms of relevant skills, knowledge and behaviours. Measuring the impact of practitioners' work in a meaningful way is one skill we should encourage, while keeping at the training's core our key values that will see us through what is still a volatile climate.

Understand how evaluation shapes practice

By Tania de St Croix, lecturer in the sociology of youth and childhood, King's College London

How and why has the policy agenda around impact come about? How does it shape practice in grassroots settings that are "difficult to measure" - youth clubs, detached projects, and specific work with young women, disabled young people, LGBTQ groups and Black young people? What do young people think about evaluation tools and processes, and how do youth workers and managers negotiate the tensions between funding requirements and evaluation that supports practice?

These questions will be investigated over the next three years by a new study at King's College London, Rethinking Impact, Evaluation and Accountability in Youth Work, funded by the Economic and Social Research Council and carried out by myself and my colleague Louise Doherty. The study seeks to understand current approaches to evaluation in youth work, why they have come about, their advantages and disadvantages, and how they are carried out in practice. We want to find out how various approaches to evaluation and monitoring are experienced by young people and practitioners, as well as understanding the perspectives of managers and administrators.

This research is important because evaluation does not simply reflect what we do - it shapes and influences our work, particularly when there are high stakes such as staff redundancies or the closure of a project or organisation. Open access, informal and youth-centred approaches are the focus of our research because they are attractive to marginalised young people, yet have been disproportionately affected by spending cuts, and are difficult to "measure".

The study will involve eight youth bodies and 150 young people, youth workers, managers, administrators, and policy makers and influencers (including funders). It adopts a qualitative approach through interviews, focus groups, participant observation and youth participatory methods such as photography, peer interviewing and film-making. While it focuses on England, where the youth impact agenda has been most intensive, it aims to learn from other jurisdictions within and beyond the UK.

The study aspires to be practical and useful to the youth work field and beyond, by contributing to knowledge of how the impact agenda plays out in practice, and sharing approaches to evaluation and accountability that are congruent with youth work practice. Our research aims to encourage further moves towards democratic and participatory approaches that place young people, practitioners and communities at the centre.

Youth work crucial to future opportunities

By Leigh Middleton, managing director, National Youth Agency

There is a well-established principle that each generation should be happier, healthier and left better off than the generation before. This is being challenged like never before. Young people are living at a point of transformation in the working and social economy.

Gen Z, iGen, or Centennial young people will be worse off than the generations before them for the first time - in the next 25 years, Oxford University scholars predict 47 per cent of traditional jobs will be replaced by artificial intelligence and automation technologies. For young people, this means a dramatic and unscripted change of attitude to the societal norms of today. The good news is young people are amazingly resilient and will adapt - but not all are treated equally by society, given the same encouragement, opportunities and the mobility to adapt to ensure they are not left behind.

Youth work, since it emerged in the industrial revolution, has supported young people to be resilient. The need for them to be supported, particularly those with fewer opportunities but with all the same incredible potential of their peers, means the business case for youth work has never been stronger - securing equality for all young people is a cornerstone of youth work.

In our submission to the Civil Society Strategy, we pressed hard for a youth covenant - a simple promise from society and cross-government to all young people to help them meet the challenges listed above. The covenant asks that young people should be "safe and secure in the modern world and treated fairly; supported in the present and ambitious for the future". To achieve this, we believe there needs to be new investment in youth work through government, business and funders.

I've been listening to evidence from witnesses to the all-party parliamentary group for young people inquiry into youth work. Young people have been eloquent in their rights for greater support through high quality youth work delivered by trained professionals and volunteers with vital life experience. We must raise the profile of practitioners who are highly skilled and equipped to support young people to benefit from an invigorated civil society.

The new Civil Society Strategy must recognise the rights of young people to be supported and their right to non-formal education as much as a formal education. When the landscape for young people's futures is so incredibly different, it is for all of us to ensure young people achieve their full potential and secure a better future than their parents - youth work is the key to unlocking and equalising their potential.

MEASURING THE IMPACT OF THE NATIONAL CITIZEN SERVICE

By Stephen Webster, head of research, NCS

NCS represents a significant social investment which is why it is critical to us that the programme is robustly tested and its impact measured through high quality evaluation studies of programme efficacy that allow us to demonstrate the strong return on investment that NCS represents to society.

This takes the form of quantitative research via a broad government impact survey with participants, alongside deeper qualitative studies of NCS graduates examining the views of the young people, their parents or guardians and their staff member on the programme. We also work closely with NCS delivery partners, who supply a significant amount of quantitative data.

We are constantly looking at ways to use our evaluation insights to refine and improve the programme itself, and have recently focused on evaluation of our innovation pilot initiatives, such as a buddy scheme pilot to help minimise attrition rates. Initiatives such as these allow us to make evidence-based decisions and help to improve the impact and reach of the programme.

One of the greatest evaluation challenges, not just for NCS but for all organisations in the sector, is to be able to demonstrate the relationship between the programme and long-term outcomes for participants. This is something we have been looking at in NCS for a while, and our ambition is to work towards running longitudinal follow-up studies for a period of five years, combining surveys with insights from government data sets, in a way that is cost-effective for the organisation.

NCS does not exist in a vacuum. The learnings that we take from our research and evaluation can also be of use to other organisations within the sector who have an interest in social cohesion, social action and social engagement - as we can learn from them.

ADCS VIEW

CUTS UNDERMINE YOUTH WORK IMPACT

By Jenny Coles, director of children's services, Hertfordshire County Council, and chair of the ADCS families, communities and young people policy committee

Youth workers operate at the earliest of early help opportunities to prevent problems from escalating and contribute to a range of positive outcomes at a community and an individual level, including diversion, improved mental health and wellbeing and engagement in alternative learning programmes. Youth workers support schools with a range of activities, from working closely with vulnerable young people experiencing adversity to future career planning. Youth workers also undertake targeted interventions in localities experiencing high levels of antisocial behaviour and violent crime or work with specific vulnerable groups. Detached youth work also lends itself to efforts to identify and disrupt child sexual exploitation by targeting known hot spots.

Despite the ongoing demand from young people for constructive activities delivered in a safe environment, and the clear benefits of this, estimates suggest 600 youth centres were lost from local communities between 2010 and 2016. Moreover, three-quarters of respondents taking part in a survey by Unison in 2016 felt falling funding had resulted in young people feeling less empowered and contributed to an increase in crime and antisocial behaviour. A recent children's commissioner for England report showed that funding for youth services has fallen by 60 per cent as money is being increasingly diverted towards safeguarding.

In a bid to retain at least some of this provision, local authorities are exploring different ways of arranging, commissioning and delivering these services, such as embedding youth workers in their early help offer. Funding for outreach work is also drawn from multiple budgets, but these alternative funding streams are far from secure. Since 2010, £500m has been removed from the Early Intervention Grant, public health budgets have decreased by £531m between 2016/17 and 2019/20, and the future of the Troubled Families programme is uncertain beyond 2020.

The government hasn't really articulated a vision for youth services, preferring to promote the National Citizen Service as a flagship programme. We are worried that without a clear policy statement, these vital services continue to be cast adrift from wider children's services and, crucially, from education. We would certainly welcome discussions about relocating the lead for youth policy from the Department of Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) to the Department for Education as a way of demonstrating the value of youth services.

Not a single minister has youth services in their brief at DCMS, nor does it feature in the departmental priorities. We would also welcome discussions with the DfE and others about the prioritisation of the wider workforce in children's services, not just social workers and teachers.

FURTHER READING

- Brathay Research Hub Evaluation Toolkit, The Brathay Trust, November 2016

- Using research evidence - a practice guide, Nesta and the Alliance for Useful Evidence, January 2016

- Four Pillars Approach, Anne Kazimirski and David Pritchard, New Philanthropy Capital, June 2014

- The future for outcomes - A practical guide to measuring outcomes for young people, National Youth Agency and Local Government Association, June 2014

- A framework of outcomes for young people, Bethia McNeil, Neil Reeder and Julia Rich, The Young Foundation, July 2012