Briefing: Youth suicide levels

Derren Hayes

Tuesday, October 29, 2019

What are the key factors behind a worrying rise in the number of young people taking their own life?

Latest figures from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) shows there was a rise in the number of children and young people taking their own life last year, raising concerns among campaigners about the level of support provided through child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS).

What does the ONS data show?

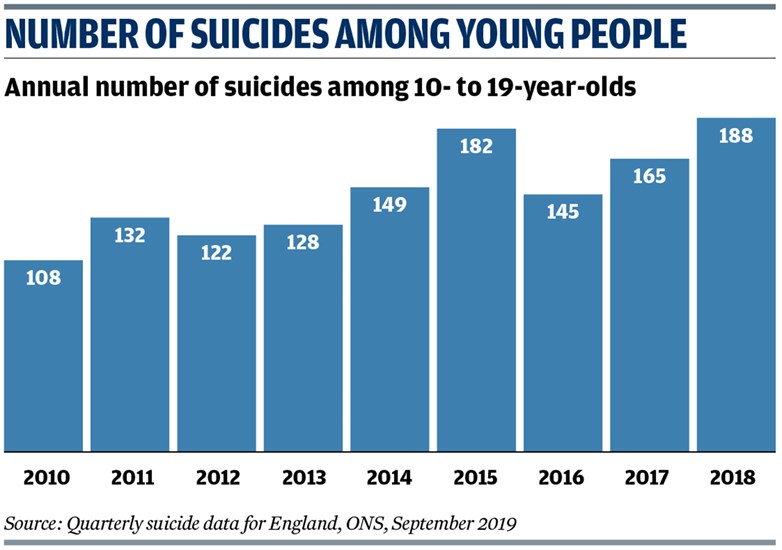

In 2018, there were 188 suicides among 10- to 19-year-olds. This was the highest annual total this decade and was 14 per cent higher than the 165 suicides recorded in 2017, which itself was 14 per cent higher than the 145 recorded in 2016. The previous highest figure this decade was 182 recorded in 2015.

Since 2010, the annual number of suicides among 10- to 19-year-olds has risen by 74 per cent (see graphic).

Is the rise likely to continue?

Worryingly, yes, judging by provisional figures for the first two quarters of this year. So far this year, 98 children and young people have taken their own life, compared to 93 in the first two quarters of 2018.

The 56 suicides of 15- to 19-year-olds recorded in the April to June period this year is the highest quarterly total this decade. The previous highest total was 50 in the fourth quarter of 2015.

What is behind the rise?

The reasons young people feel suicidal are often complex, explains Tom Madders, director of campaigns at children's mental health charity YoungMinds.

Traumatic experiences at a young age - such as bereavement, bullying or abuse - can have a major impact on mental health, as can school pressure, concerns about appearance and difficult relationships with their family or friends, Madders adds.

Lack of support at an early stage can also be a significant factor for someone becoming suicidal, says Madders. "For many young people, it is still really difficult to get early help for their mental health when they first reach out for support.

"Facing a long waiting list or being refused treatment for not meeting the threshold for treatment often results in problems getting worse. We hear about children who have started to self-harm, become suicidal or dropped out of school while waiting for a CAMHS appointment. Many young people who are suicidal still find it difficult to reach out for help until they hit crisis point."

Do the figures reflect the full extent of the problem?

NHS figures show a rise in emotional disorders among children, while a recent study by The Lancet showed an alarming increase in self-harm, particularly among young people.

"The number of young people arriving in A&E with a mental health problem has also tripled since 2010," says Madders. "In some cases, this is because they haven't been able to get help anywhere else. It's often left to those around young people - like friends, family or teachers - to try to provide support."

Are there any other key trends?

Boys continue to be the higher risk group. From April to June this year, 39 boys aged between 15 and 19 took their own life, compared with 17 girls. In the first quarter of the year, 25 boys took their own life, compared with 12 girls.

This disparity between boys and girls can be seen in the annual figures over the past decade.

Since 2010, in every year bar one, two-thirds of children and young people taking their own life have been boys. Only in 2017 did the proportion of girls committing suicide rise above that level - to 34 per cent.

What does the government say?

The Department of Health and Social Care said: "Every suicide is a preventable death and we are working urgently with partners across government, businesses and communities to tackle this problem.

"All councils have a suicide prevention plan in place backed by £25m and we work closely with them to ensure they are effective.

"We are transforming mental health services with a planned record spend of £12.1bn this year and announced a further expansion of mental health services in our Long Term Plan for the NHS, with an additional £2.3bn in real terms by 2024."

Does this go far enough?

YoungMinds is calling for a cross-government approach, so ministers look at the factors that are making mental health worse and ensure that government policies have a positive effect.

"At present, the NHS is only able to support about one-third of young people with a diagnosable condition," says Madders. "With rising demand, the NHS can't and shouldn't meet the scale of need on its own, so we need government to invest in early intervention, community-based support and in addressing the factors that can lead to worse mental health."

What more can services do?

"As part of our call for a cross-government approach that focuses on tackling emerging mental health problems, we also want to see all professionals who work with children get some training on how to support a young person struggling with their mental health," says Madders.

This, he adds, should see professionals including teachers, nursery staff, social workers and the police having a clear understanding of the links between trauma and behaviour, and how best to provide support.

"We want to ensure that young people have a range of places to go when they need help," he says. "Informal spaces, where young people can get early support, will ensure they can talk to a trusted adult, outside school. This can have huge benefits for a young person going through a difficult time, but years of cuts have meant that many youth centres have shut down.

"We are calling for a new strategy that makes early support in the community a priority."