Advice on using ACE enquiry

Derren Hayes, Alana Ryan and Karen Bateson

Tuesday, June 26, 2018

Experts say more research is needed on impact of routine enquiry into adverse childhood experiences.

The science and technology committee's inquiry into evidence-based early years interventions recently heard from experts about the impact of adverse childhood experiences (ACE).

Once complete, the investigation is likely to generate a new report with recommendations for the government regarding the incorporation of ACE research into early intervention work.

ACE is a term used to describe a range of abusive and neglectful experiences in childhood.

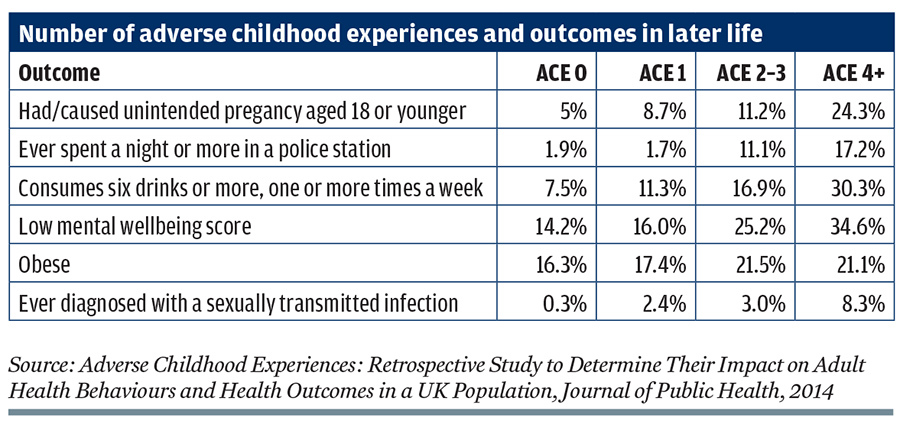

Research shows that almost half the population in England and Wales reported experiencing at least one ACE, with more than eight per cent of people in England reporting four or more. A 2014 study highlighted the negative health outcomes associated with ACEs and how this can increase pressure on health services (see table).

Some experts believe that using a tool to detect ACEs in children could help professionals get early support in place to reduce the risk of negative outcomes.

The NSPCC's Alana Ryan and Karen Bateson say the ACE agenda should be welcomed by the public health sector as it sheds further light on the links between childhood adversity such as abuse and physical and mental health problems in adulthood.

While Bateson and Ryan welcome the growing awareness around the potential negative impacts of adverse childhood experiences and the need for preventative policy solutions, here they outline six key reasons for practitioners to be cautious in their translation of ACE research:

The ACEs framework is proving a useful lens for policymakers to make the case for prevention and early intervention. It demonstrates why child maltreatment is a mainstream public health issue. For new audiences, ACEs are proving revelatory and highly engaging. There is a renewed motivation for action in many quarters.

By shifting the thinking from "what's wrong with you?" to "what's happened to you?", the ACEs agenda has helped professionals be more attuned to the relevance of early experiences and the impact these can have on all aspects of personal development and functioning. There appears to be value in using an ACE lens to have deeper conversations with people about what's happening in their lives and to encourage help seeking.

Although there is much to be celebrated about evidence that gives wings to the prevention agenda, we would question whether the research is fully practice ready. Given there has not yet been sufficient investigation into the after effects of ACE enquiry, we should approach roll-out with caution given the potential for unintended harm.

For those thinking about incorporating ACE into practice, here are six considerations:

1. Risk of unintended harm

Not everyone wants to be asked about childhood trauma, so enquiry needs to be sensitively done within a supportive relationship. Most people asked do seem to find ACE enquiry acceptable and non-aversive, maybe even welcome, but there is little published follow-up research. We don't understand the potential risks associated with routine enquiry and so practitioners must exercise caution.

2. Look beyond ACE

Although exposure to ACE represents a risk factor for negative outcomes, the link is not deterministic. Not all individuals facing the same experiences will have the same outcomes. The ACE tool does not measure magnitude, severity, duration or the age at which the person experienced adversity. Individual resilience, wider support networks and access to evidence based interventions can all help to break the link.

3. Caution with children

At present, there is limited evidence to recommend the ACE enquiry tool use with children. The majority of research has been retrospectively conducted with adults and we know little about how it could be used appropriately with children. There are ethical considerations about asking parental consent or for parents to complete the ACE tool on behalf of a child, and about how ACE scores are recorded, updated and shared.

4. ACEs are not an exhaustive list

Experiences like growing up in the care or asylum system can also exert a significant negative impact on child wellbeing. In some UK research, neglect has not been explicitly recognised, which is a major omission. We should be cautious about limiting our understanding of adversity to a set checklist; many non-specified disadvantages can exert a toll on individual wellbeing.

5. Low scores can mask trauma

No two instances of one type of maltreatment or adversity will be the same, and one continuously present and severe ACE may be as psychologically harmful as the presence of four co-occurring ACEs over a short period of time. There is an inherent risk in using cut-off scores to indicate need.

6. After enquiry, what next?

Not everyone who discloses historical trauma will want or need specialist help; sometimes the compassionate recognition of what happened will be helpful in itself. However, individuals who consent to ACE enquiry must have access to appropriate support where needed. This means ensuring that local services have the capacity to deliver a trauma-informed response for both children and adults.

The challenge for practitioners and policymakers is to capitalise on the enthusiasm the ACE research has generated, while maintaining a critical eye on how it could be improved and applied with care in practice.

- Alana Ryan is senior policy and public affairs officer, and Karen Bateson is development and impact manager at NSPCC

Had/caused unintended pregancy aged 18 or younger 5% 8.7% 11.2% 24.3%

Ever spent a night or more in a police station 1.9% 1.7% 11.1% 17.2%

Consumes six drinks or more, one or more times a week 7.5% 11.3% 16.9% 30.3%

Low mental wellbeing score 14.2% 16.0% 25.2% 34.6%

Obese 16.3% 17.4% 21.5% 21.1%

Ever diagnosed with a sexually transmitted infection 0.3% 2.4% 3.0% 8.3%

Source: Adverse Childhood Experiences: Retrospective Study to Determine Their Impact on Adult Health Behaviours and Health Outcomes in a UK Population, Journal of Public Health, 2014

]]