The international children’s charity Unicef has published its 10th report card comparing how economically advanced countries treat their children.

In the past, the UK has fared badly, particularly in the much-cited seventh report card published in 2007, which ranked the UK at the bottom of the league table for child wellbeing out of 20 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries.

The latest card focuses on child poverty and deprivation, but comes with a major caveat – the findings are based on data from 2009. On this basis, the UK has shown a marked improvement on its previous performances.

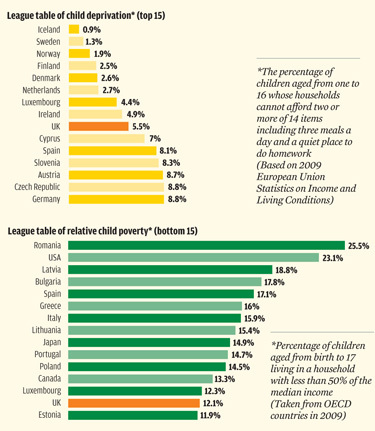

It is based on two measures (see graphs). On the one hand, the report examines relative poverty measured by households living below 50 per cent of the national median income. On this scale, the UK produced an average show, coming 22nd out of 35 OECD countries, above those including Romania and the US, but below Estonia and Hungary.

Child deprivation

On the other, the charity uses EU data to rank 29 countries according to child deprivation. This is measured by the percentage of children lacking two or more of 14 selected items. These include three meals a day; fresh fruit and vegetables every day; age-appropriate books; regular leisure activities; a quiet place to do homework, and an internet connection.

On this, the UK fared much better in coming ninth, above Germany, France and Italy, but below Ireland, Norway and Finland.

“The report looks at relative income poverty, but also material deprivation,” says Sam Whyte, domestic policy and parliamentary manager at Unicef UK. “It is the combination of the two that gives us the best possible picture.”

In a recent speech, the government’s adviser on poverty, Labour MP Frank Field, criticised the current focus on assessing household incomes, warning “the measures as they stand promote a single policy of pushing household income above an arbitrary line”.

Field’s report on child poverty, published in December 2010, recommended using an “index of life opportunities” that would consider children’s development, parenting and environment.

While Unicef commends exploration of further measurements, the charity warns that a focus on measuring income remains essential.

“Sometimes the importance of the relative income measure is downplayed and what the report card shows is it is that very focus that has helped the UK make progress up to 2009 in reducing child poverty,” Whyte says.

Where the UK did exceptionally well was in comparisons of each country’s spend on families and children. Only France spent more on tax breaks and services for children and families out of 35 countries.

But the age of the data does not take account of current government polices. Unicef cites the Institute for Fiscal Studies forecast, which predicts a reversal of progress on child poverty with a rise almost certain in 2013.

Whyte says that while the coalition government has retained a commitment to the targets in the Child Poverty Act, any loss of focus on monitoring and improving family income could have disastrous effects.

“Although we did better in the early years of the economic crisis in tackling child poverty, the report card sounds a warning that current UK government policies may result in more children growing up in poverty, while the government is focusing on cutting the deficit,” she says.

Child poverty strategy

“For us, policy to tackle the deficit must not harm children. The targets in the Child Poverty Act aren’t the problem; it is the action plan that is in place to meet them.

“We are asking the government to look again at the child poverty strategy and set out a more credible plan to make more progress towards the 2020 target to eradicate child poverty.”

While austerity measures have been condemned for damaging family incomes, the government maintains that schemes such as the pupil premium for disadvantaged students, free childcare for disadvantaged two-year-olds offer and universal parenting classes will help ease the burden.

But according to Unicef, these measures could lack impact. “Previous report cards show these early intervention initiatives can be effective in reducing inequality,” Whyte says. “The issue is if they come without an overriding focus on tackling family income, they are completely undermined.”

Jonathan Bradshaw is professor of social policy at the University of York. His work fed into Unicef’s latest report card. He believes the impact of the recession and subsequent austerity measures will push the UK back down future league tables.

“This government has loaded all the cuts on families with children,” he says. “There is absolutely no doubt that child poverty is actually increasing. This report card shows the high point of our achievements, but the current government has a long way to go.

“We are still not doing as well as we should be given the level of wealth in the UK and I’m afraid that the coalition’s policies are going to make it much worse.”

Unicef’s 10th report card

- In the league table of child deprivation, 29 countries are measured on the percentage of children lacking two or more of 14 items considered to be essential, including a quiet place to study and three meals a day, with the UK coming ninth

- In the league table of relative child poverty, 35 countries are measured on the percentage of children living in households with an income less than 50 per cent of the median income, with the UK coming 22nd

- The UK came second out of 35 countries for its spend on benefits, tax breaks and services for families and children as a percentage of its GDP, with only France achieving better. The UK spends twice as much as countries including Canada and Japan

- When comparing the gap between the overall poverty rate and child poverty rate in each country, the UK came 19th out of 35 countries, behind Estonia, Japan, Malta and Canada, but was more successful than France and the US