How concurrent planning is helping to speed up the adoption process in London

CYP Now reporter

Monday, October 15, 2012

Coram operates the only specialist centre for concurrent planning, which aims to improve the stability and wellbeing of young children taken into care

Project Coram's Concurrent Planning Service

Funding Placing a child via the service costs about £27,000 for the adoption and £150 a week for the foster placement, while supervised contact costs about £35 to £50 an hour

Purpose To improve stability and wellbeing of young children taken into care

Background Concurrent planning involves recruiting individuals and couples to act as foster carers for young children who are highly unlikely to be able to return to their birth parents.

Carers are also approved adopters so can go on to adopt babies, avoiding the disruption and stress caused by moving around and speeding up the adoption process.

It is an approach advocated in the government's action plan for tackling adoption, published in April. Children's charity Coram operates the

only specialist centre for concurrent planning in the UK, having launched the service in 1999.

Action The service works in partnership with several London councils and offers spot purchasing to others in or near the capital. Councils make the decision to opt for concurrent planning as part of a child's care plan agreed by the court. The majority of referrals are made before a baby has been born to a mother with serious problems such as drug or alcohol addiction or severe mental illness.

Concurrent carers recruited by Coram will only be involved with one child at a time and must be prepared to work with the child's birth family. Managing that relationship is one of the most challenging aspects of the scheme, explains Jeanne Kaniuk, Coram's head of adoption.

"These babies are unlikely to be able to go back home, but you still have to manage contact with the birth parents", she says. "What often happens is that a form of mutual respect develops between the birth parents and foster carers. The birth parents see the carers really are looking after their child, while carers see that the parents are not ‘bad people' but people whose circumstances are such that they just can't cope."

Another vital element is complete openness with birth families. "The possibility of these children going back home is small," says Kaniuk. "You need to respect people and be honest about that and the fact they won't get their baby back unless they address their issues, whether that is violence and anger or alcohol and drugs, and work very hard."

Sometimes birth parents decide adoption is the best option. Most are kept updated on their child through "letterbox" schemes where adopters and birth parents exchange news without addresses being identified, although some may have limited contact after adoption.

The service has also helped councils including Cambridgeshire to set up concurrent planning services and has launched a subscription scheme to enable authorities to get more information on the approach.

Outcome An interim report from Coram's Concurrent Planning Study, published in July, concluded the project had successfully boosted continuity of placements for young children and speeded up the adoption process.

Between 2000 and 2011, 59 children were placed through the scheme - 61 per cent of them were referred at or before birth, while 95 per cent of referrals were made before a child's first birthday.

Two children are currently going through court proceedings.

Of the remaining 57, none experienced placement disruption and none returned to care. Three (five per cent) returned to the care of a family member, while 54 (95 per cent) were adopted by concurrent carers.

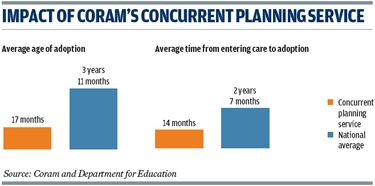

On average, children were 17 months old at the date of adoption compared with a national average - over the last five years - of three years and 11 months.

On average, it took 14 months from entering care to adoption, compared with a national average of two years and seven months.

Ninety-six per cent of children adopted through concurrent planning met the current national adoption scorecard target and waited less than 21 months between entering care and moving in with their adoptive family, compared with a national figure of 58 per cent.

If you think your project is worthy of inclusion, email supporting

data to ravi.chandiramani@markallengroup.com