Spending returns revamp will lead to better decisions for children

John Freeman

Tuesday, February 28, 2017

Study finds section 251 returns system to record education and children's services spending produces data that is often inaccurate and of little use. John Freeman says only an overhaul of the process will deliver improvements.

One of the very earliest sayings in the world of IT was "Garbage In, Garbage Out" or "GIGO". This was a vital warning to early users of the technology, too many of whom were seduced into thinking that the precision of a number was guaranteed simply because it had been produced by a computer. I wish I could say this never happens today.

By contrast, we are now continually told that we are operating in the world of "big data" in which it is possible to mine huge datasets to find new truths to inform policy and practice.

Section 251 returns on children's services finances illustrate these points well. Local authorities return more than 1,000 separate finance figures every year for children's services (see box).

Earlier research by the Local Government Association showed the accuracy of many of these returns are suspect and the aggregate analyses cannot be relied upon.

However, since they provide the only national information on spending, the government has little alternative to relying on the suspect data to assess what is going on out there in local authorities.

Andrew Rome's meticulous and detailed analysis, Section 251 Data: Testing Accuracy and a Proposed Alternative - carried out for the Department for Education in 2015, but only now published - confirms the problematic nature of these financial statistics, and proposes changes that will improve the position.

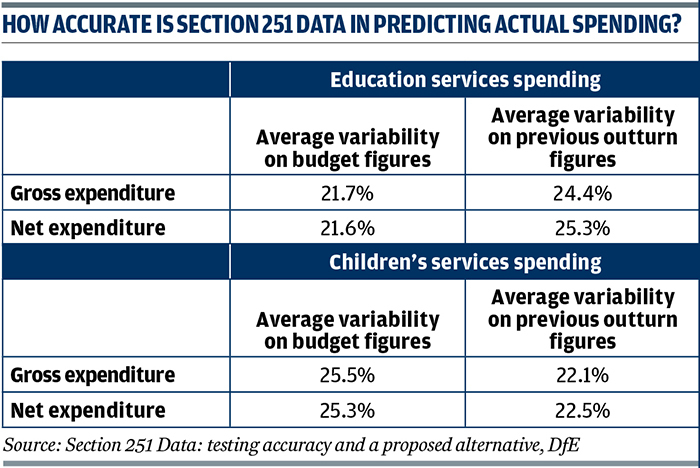

His first proposal is to abandon budget returns which, as his comprehensive scrutiny shows, are less reliable on children's services spending than simply using the previous year's spending return (see table). His second proposal is to move to six-monthly rather than yearly returns to improve the timeliness of the analyses (see box).

These would be real and worthwhile improvements, and I support them. But by themselves, they are not sufficient and I would argue a more fundamental realignment of the whole process is needed to build in incentives both to improve the quality of the data returns and to encourage their use to improve practice.

The central problem is that s251 of the Apprenticeships, Skills, Children and Learning Act 2009 makes clear that the collection is for central government purposes. As Rome says: "Users describe the functions of s251 as accountability and monitoring, policy development, and to inform parliament and the public."

Local collection, central use

Note that these "users" are located in central government, and that there is a complete disconnect between the local task of collecting all this data and how it is used in Whitehall. At a time of huge cuts in local authorities' spending, there is little incentive to increase the effort put in to improve data returns, as there is no direct benefit for doing so, nor penalty for submitting questionable data.

However, as Rome says, while some local authorities do not see the point of the returns, viewing them only as an unhelpful burden, others do value them and the subsequent analysis. This illustrates a key problem: that the local authorities that do value the analyses have to rely on the highly questionable data returns from the local authorities that do not.

Another challenge for the whole process is that central government keeps changing the ground rules of what is collected, leading to lack of year-on-year comparability. This is a problem endemic to the DfE, with examination and assessment measures changing every year, so any attempts to compare children's educational progress over time are bedevilled by changes in measures.

Based on the announcements that have already been made, there will be changes in the education performance statistics that are collected and published every single year until 2024.

One obvious improvement in the system would be for the DfE to commit to making minor changes only, with core measures remaining the same for a lengthy period.

Having said all that, all is not lost and there is, already, a better model for improved analysis.

The Chartered Institute for Public Finance and Accountancy (Cipfa) children's services benchmarking club, where local authorities see sufficient benefit to pay to join, has the benefit of having better comparative data to inform local policy development - but everything is still driven from the flawed national returns.

A realignment of the whole process so that it supports both national and local policy development would be an obvious way forward that would result in better incentives and motivation for local authorities to improve the quality of the returns.

Sector-led improvement

We have the basis for this realignment already in place, with a general commitment from the DfE and local authorities to "sector-led improvement". If the whole infrastructure of sector-led improvement were to be informed by accurate, meaningful and timely financial information, comparable between local authorities and over time, our learning about "what works" and what is needed for improvements would be hugely empowered.

What is required is a genuine partnership involving local and national government. This would bring together senior staff from children's services and finance, nationally and locally, alongside CIPFA.

The aim would be to implement Rome's proposed improvements and going further, to ensure that the data and analyses produced are capable of being used properly by all parts of the sector - not just Whitehall.

Andreas Schleicher, from the Organisation of Economic Cooperation and Development, is correct when when he says that the starting point of any systematic improvement has to be the data.

Remember, though, that another of the maxims of the IT world is that we need always to move from data, through information, to knowledge and understanding.

Only with effective analysis of reliable data on both finances and practice can we hope to learn how to improve outcomes for children across the breadth of children's services and in every local authority.

It is not impossible, but it will require local authorities and the DfE to work together in a way that does not privilege either national or local government, but recognises that working together is to the benefit of all.

AT-A-GLANCE GUIDE TO SECTION 251 RETURNS

Local Authorities are required under section 251 (s251) of the Apprenticeships, Skills, Children and Learning Act 2009 to prepare and submit statements of education and children's services spending and income. This data is collected by the Department for Education and the Education Funding Agency and published by the department.

Under current processes, each of 152 councils in England reports twice a year, first with a budget statement for the year from 1 April to 31 March, and then after the year has expired, with an "outturn" statement.

The processes involved in submitting, checking and aggregating data often result in publication of s251 budget information more than six months into the year it covers. Outturn data is published around nine months after the end of the year it relates to. Timeliness of s251 information is therefore perceived to be a problem for many.

A typical budget return by an authority reports 105 lines of details and totals, with up to eight columns of analysis for some of the lines. A typical budget return has up to 490 data items reported.

Outturn figures are reported with education data separated out from children's services data.

Around £40bn of expenditure annually is covered by the s251 data.

SECTION 251 DATA STUDY - SCOPE, FINDINGS AND PROPOSALS FOR CHANGE

The primary task of the project was to examine the most recent s251 data and to focus on testing the relative accuracy of the budget and of the previous year's outturn as predictors for current year's stated outturn.

Outturn data for 2013/14 and 2012/13, and budget data for 2013/14 were already published at the outset of the project and outturn and budget for 2014/15 became available for testing in December 2015.

Substantive testing of these datasets detected and measured the variability of outturn compared to the two predictors: budget and previous year outturn.

Results of predictor testing for education expenditure and income differ materially from the results for children's services. Councils identify the influence of unpredictable factors such as the number of looked-after children as a key reason for the variability.

The key conclusions from the data testing were: for education information, the process of setting a budget produces the better predictor of actual outturn, but for children's services information, the testing shows that local authorities would have been more accurate simply using the previous year's outturn as a predictor of current year outturn rather than producing a budget (see table).

The project developed an alternative model for s251 reporting. This proposed the discontinuation of the production of an annual budget and instead use six-monthly outturn reporting as a basis for monitoring and prediction. The model has significant advantages for improvement in accuracy and timeliness of data and, as it involves just two data collections, would not add excessive burden to local authorities.

The report outlines the advantages and disadvantages of three different potential courses of action, ranging from making no changes to current practice, through to a wholesale move to the alternative model, with a partial implementation of that model for children's services information as the third option.

Based on the study findings, the alternative model would have clearest application to children's services.

The project activities also identified which parts of the s251 reporting could be reduced. It concludes that between 26 and 55 per cent of detailed data items can be removed from the return. This reduction in burden on councils would help to counteract any additional work associated with the introduction of the new model.

John Freeman is a children's services consultant