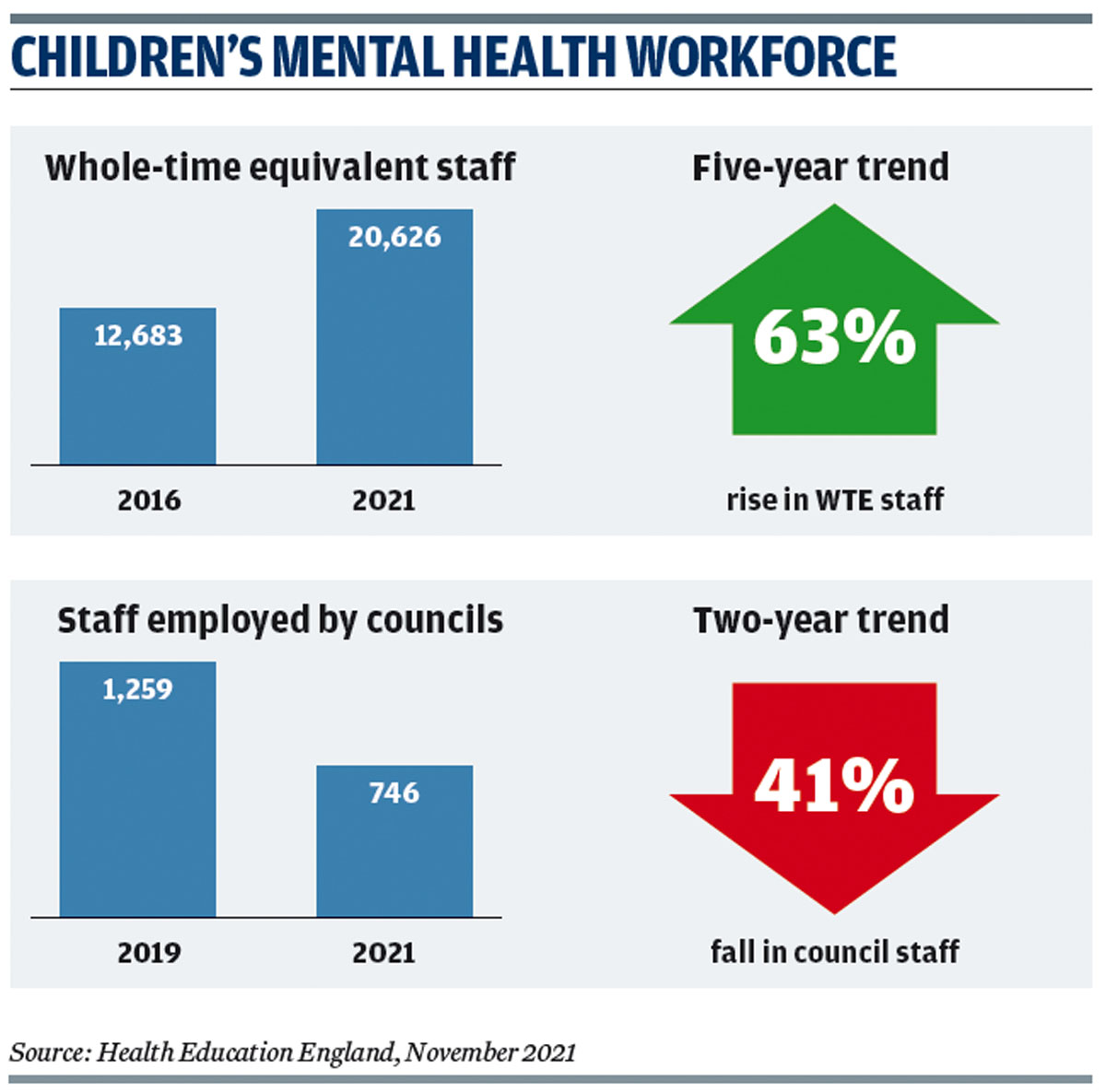

A survey of employers reveals there has been a substantial rise in the children’s mental health workforce over the past five years.

Data collected by NHS Benchmarking Network on behalf of Health Education England (HEE) shows 20,626 whole-time equivalent (WTE) staff were employed across NHS, voluntary and local authority providers on 31 March 2021, 39 per cent higher than in 2019 and nearly two-thirds the level recorded in 2016 (see graphics).

The rise has been welcomed by mental health campaigners and service providers, who point to the importance of policy initiatives like the NHS Long Term Plan and children’s mental health green paper as instrumental in boosting the status and profile of the sector.

Register Now to Continue Reading

Thank you for visiting Children & Young People Now and making use of our archive of more than 60,000 expert features, topics hubs, case studies and policy updates. Why not register today and enjoy the following great benefits:

What's Included

-

Free access to 4 subscriber-only articles per month

-

Email newsletter providing advice and guidance across the sector

Already have an account? Sign in here