As councils finalise their spending plans for the coming year, for many areas it signals a new wave of cuts and closures to children’s centres services.

In February, Suffolk Council announced plans to close at least 11 centres, Nottinghamshire Council approved three closures and an “outstanding”-rated centre in Calderdale also learnt it is to shut.

With many councils still to finalise budgets, and local government funding pressures showing no sign of easing, the likelihood is that more children’s centres will face closure or cuts in the coming weeks.

Decade of decline

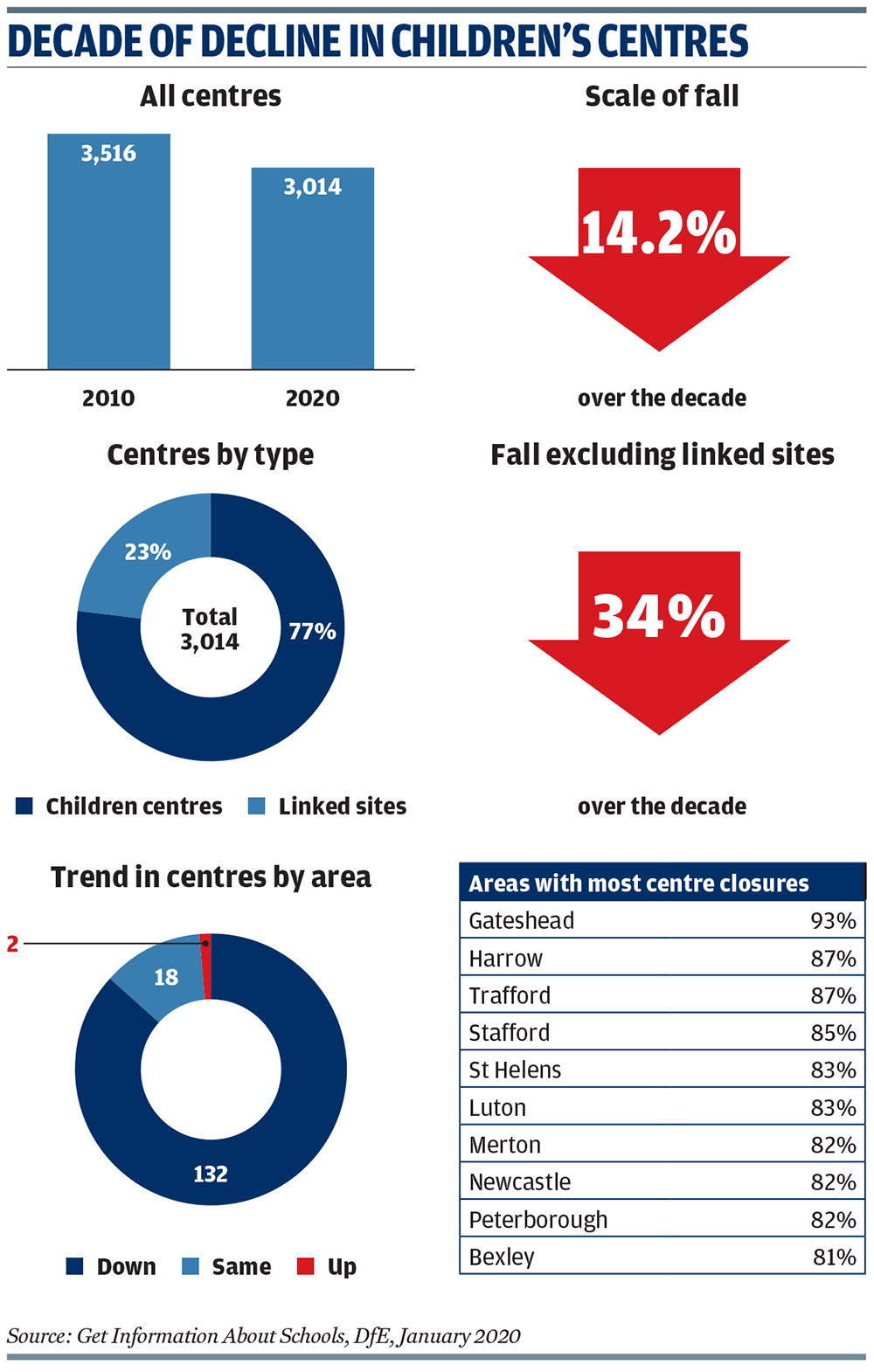

The bleak outlook follows the publication of Department for Education figures that show the number of children’s centres open in England fell by a third between April 2010 and January 2020 (see graphics).

Register Now to Continue Reading

Thank you for visiting Children & Young People Now and making use of our archive of more than 60,000 expert features, topics hubs, case studies and policy updates. Why not register today and enjoy the following great benefits:

What's Included

-

Free access to 4 subscriber-only articles per month

-

Email newsletter providing advice and guidance across the sector

Already have an account? Sign in here