Adverse Childhood Experiences: Research evidence

Tuesday, September 29, 2020

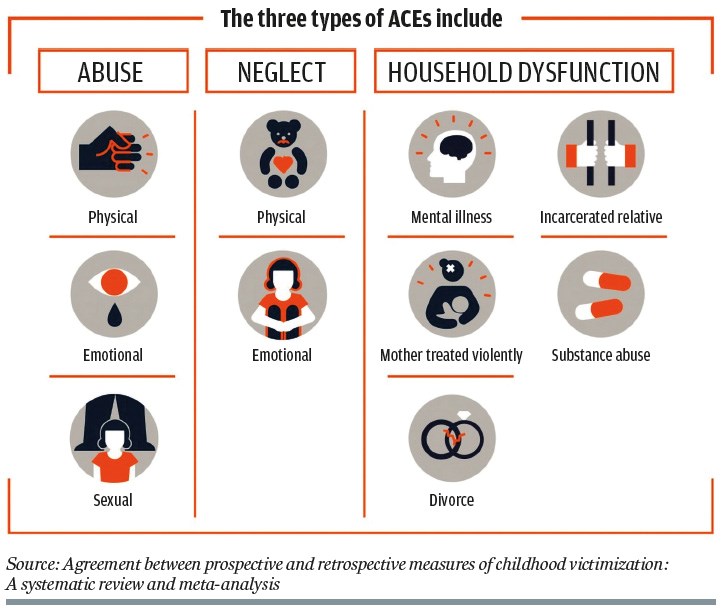

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are traditionally understood as 10 forms of abuse, neglect and family dysfunction that typically increase children’s experiences of trauma and stress.

The landmark 1998 ACEs study asked adults to recollect their history of these experiences and then compared their answers to their health status, as verified by a medical examination (Felitti, et al, 1998). The study observed that four or more ACEs before the age of 18 significantly increased the likelihood of poor adult outcomes in comparison to a history of no ACEs. For example, four or more ACEs were observed to more than double the risk of heart disease, quadruple the risk of lung disease and increase the risk of suicide by at least 12-fold in comparison to one or no ACEs.

This “dose-response” relationship between ACEs and negative life outcomes led the ACE study’s authors to conclude that traumatic circumstances occurring in childhood could trigger a series of events that increased the likelihood of a life-threatening disease. Their conclusion was then strengthened by findings from a string of ACE studies that also confirmed a connection between ACEs and various life-threatening conditions. The consistency of these findings, coupled with new evidence suggesting that early trauma could possibly disrupt the development of the immune system, led many to assume that four or more ACEs would inevitably lead to early death.

Universal ACE screening has therefore been introduced in many areas to help individuals who have experienced multiple ACEs receive further help.

However, the evidence underpinning these conclusions is not as strong as many might think. For example, the retrospective survey design used in most ACE studies is inadequate for confirming judgments about causal relationships, meaning that claims that link ACEs to early death are likely premature.

In the first paper, we describe why retrospective surveys are inappropriate for testing causal relationships, on the basis of inaccuracies in adults’ recollections of childhood events.

In the second paper, we consider findings from a study that has employed a more robust, prospective design that is better able to observe (but not prove) the potential causal relationship between ACEs and later adult outcomes. This study tracked the adverse experiences of twins from the ages of five to 18, observing a strong and graded relationship between the number and severity of ACEs experienced in childhood and the presence of problematic mental health symptoms in adolescence. Such findings increase our confidence that high levels of ACEs significantly disrupt children’s psychological functioning.

In the third paper, we then consider the potential causal relationship between ACEs and poor physical development. This study involved a systematic review of prospective studies that compared ACEs to biomarkers of physical health collected at regular intervals throughout childhood. In contrast to the second paper, this study failed to confirm any relationship between ACEs and physical health indicators, suggesting that ACEs may not be as disruptive to children’s physical health as once was assumed.

It may be that this link might better be explained by other processes occurring in later life, such as health harming behaviours involving smoking, alcohol or substance misuse.

Finally, we consider the extent to which universal ACE screening is appropriate for identifying individuals in need of further treatment. The study described in the fourth paper shows that many screening practices are in fact inadequate for making treatment decisions and may discourage children and parents with a history of ACEs from seeking help.

EXPERT VIEW

We need to do something to stop ACEs, but universal ACE screening is probably not the best place to start

By Kirsten Asmussen, head of what works, Early Intervention Foundation

There is no question that adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are bad. Six ACE categories are forms of child maltreatment that are punishable by law and four involve negative family circumstances that are typically distressing for all family members.

Every child has the right to grow up in a home that is free from abuse, neglect and family dysfunction and this reason alone should be sufficient to introduce comprehensive measures to stop and reduce ACEs.

However, evidence from the landmark 1998 ACE study makes the need for these measures all the more compelling. This study not only observed that four or more ACEs dramatically increase the likelihood of serious adult mental health problems (an association well established in the child maltreatment literature), but also many life-threatening diseases such as cancer, heart disease and respiratory failure. These findings mean that ACEs could potentially result in early death if nothing is done to stop or reduce them.

It is therefore not surprising that many view universal ACE screening as a logical way to identify individuals with a history of ACEs and offer them further help. However, the evidence reviewed here suggests that implementing universal screening might be a bit premature.

First, the review found that most ACE measures have not yet been sufficiently validated to determine risk or harm at the individual level. While scoring practices might provide some insight into the public health burden represented by four or more ACEs, they provide little value when it comes to determining whether a specific individual might benefit from further treatment. This means that at the very least, ACE measures should undergo further testing before all individuals are screened.

Second, we are concerned that universal ACE screening may cause unintentional harm, especially in light of recent evidence showing that vulnerable individuals (those with a history of multiple ACEs) are uncomfortable when asked about their history of ACEs. This means that universal screening could potentially deter children and adults from seeking further help, even when validated measures are used.

Protocols must therefore also be tested to ensure that screening practices do not cause unintentional harm or stigma. Universal screening conducted in the absence of tested protocols otherwise represents bad practice and should be avoided.

Third, universal screening is both wasteful and unethical if it does not directly lead to evidence-based treatments. Although some have argued that the experience of screening might be beneficial in its own right, this theory needs to be explicitly tested before it is accepted as fact.

In EIF’s review – Adverse Childhood Experiences, what we know, what we don’t know and what should happen next – more than 30 interventions with strong evidence of either preventing or treating ACEs were identified.

We recommend that more time and money be spent in offering these interventions, before investing any further in untested ACE screening practices.

Simultaneously, ACEs screening measures and protocols should undergo further testing and development to make sure they do not cause any unintended harm and efficiently lead vulnerable individuals to receiving effective treatment.

- The Early Intervention Foundation is a What Works Centre that champions and supports the use of effective early intervention to improve the lives of children and young people at risk of experiencing poor outcomes

- Read more in the Adverse Childhood Experiences Special Report