Special Report: Technology in Social Work - Research evidence

NSPCC

Tuesday, November 8, 2016

The research section for this special report is based on a selection of academic studies which have been explored and summarised by Research in Practice (www.rip.org.uk), part of the Dartington Hall Trust.

STUDY 1

‘Rosie 2' A Child Protection Simulation: Perspectives on Neglect and the ‘Unconscious at Work'

Jane Reeves, Isobel Drew, David Shemmings and Heather Ferguson, Child Abuse Review, (2015)

The complexity of child protection places heavy demands on professionals making decisions in difficult circumstances. These stresses can affect workers' health and ability to be reflective, leading to "compassion fatigue", "burnout" and "secondary trauma". One way forward may be through the acknowledgement, engagement, support and supervision of emotion in practice.

Aiming to support safeguarding professionals to practice the complex skills involved in working with neglect, the University of Kent has developed a child protection simulation - "Rosie 2". It follows a social worker and health visitor on a virtual home visit to a family where neglect is a significant concern. This pilot study tracks the emotional responses of eight social workers, five health visitors and 11 control group members to the simulation using eye tracker technology and facial recognition software. In so doing, it provides information on the use of simulations for child protection training and how professionals might be supported to be aware of and regulate their emotional responses.

Results

The results indicated that the prevailing emotion exhibited by this sample group was a "neutral" response. There were differences between the groups, with health visitors displaying more sadness and social workers demonstrating greater surprise and disgust. A control group consisting of university-educated non-professionals showed more anger and sadness than the two groups of professionals.

Discussion

It is possible that the control group were more likely to expose their reactions, while professionals become adept at hiding some emotions; this is something that warrants further inquiry. It may be encouraging that professionals are better able to manage their emotions than non-professionals. However, as previous research by Gibbs (2009), Halton (2004) and Menzies-Lyth (1988) point out, this repression could also indicate the inappropriate management of anxiety. Gibbs identifies that "individuals working in emotionally charged arenas like child protection can collectively, often unconsciously and collusively develop defences to allay their anxiety".

Without challenge, emotions can compromise and cloud decision-making and can accommodate "untested assumptions, biases and personal beliefs", Gibbs found. Meanwhile, Conrad and Keller-Guenther, in 2006 research, also suggest that burnout is associated with increasing emotional distance from people and situations.

Sadness dominated the emotional responses of the small group of health visitors. This suggests clear links with compassion fatigue, whereby professionals internalise the trauma of their clients and could, in the longer term, develop a negative emotional response. This finding by Conrad and Keller-Guenther raises questions about the exploration of emotion within supervisory sessions.

Additionally, there was a significant gap between the levels of "disgust" expressed by these two professional groups. The social workers consistently exhibited higher levels of disgust than health visitors. What this sense of disgust means for communication, assessment and relationship building with families is worthy of further analysis. Such responses may well affect judgment and emotional functioning in working with families and may be transmitted non-verbally to them.

Ferguson highlights the contemporary practice dilemma of organisational cultures that leave little room for emotion, and where "admitting to fears and other feelings of disgust which appear to judge and oppress people who are invariably already subordinated has become virtually taboo". A number of authors have responded to the surfacing of unconscious and irrational responses in safeguarding practice and the significant impact of professionals' emotional states on the relationship with the client. Child protection practitioners must be able to identify and respond to negative emotions and anxiety in order to function effectively found Cooper, (2005), while Morrison (2005) concluded well-managed reflective supervision plays a critical role here.

Implications for practice

This is a very small study but the findings suggest value in the use of simulations providing immersive, realistic environments for child protection training. The authors remind us of the link between the wellbeing and emotional analysis of the practitioner and positive and optimum engagement with children and families. The main implication is that reflective supervision is needed to facilitate reflection and discussion on emotional responses in the management of cases.

STUDY 2

Facts With Feelings - Social Workers' Experiences of Sharing Information Across Team and Agency Borders to Safeguard Children

Amanda Lees, Child and Family Social Work, Advance access (2016)

Information sharing solutions need to be better informed by an understanding of the role of emotions and workplace culture in information management. Here, Lees considers practitioners' experiences of sharing information across teams in one local authority.

Since Lord Laming's 2003 report following the death of Victoria Climbié, the dominance of techno-rational conceptualisations of information sharing has been challenged. Sharing information takes place in social context, affected by:

- Professional culture (Hunt and van der Arend, 2002; Richardson and Asthana, 2006)

- Organisational structures (Bellamy et al, 2008)

- Practice at the policy, systems and individual levels (Richardson, 2007)

- The unclear, emergent nature of some of the information in child protection social work (Munro, 2005)

- Emotional responses to the work (Horwath, 2007; Thompson, 2010)

In 2005 research, Cooper highlighted the difference between policymakers' "surface" level perceptions of information sharing as being about structures and procedures, and the "depth" understanding of practitioners about how it feels to do child protection work.

For the purposes of this study, Lees undertook observation, 32 semi-structured interviews and document analysis across a referral screening team (RST), initial assessment team and longer term team in one local authority for two weeks. Observations included day-to-day office activities and multi-agency meetings on and off site, and were focused on the events taking place, the emotional atmosphere, and the researcher's inner experience.

The surface of information sharing

When asked about activities integral to information sharing, practitioners talked of collecting, interpreting and communicating information. Recording of information was also discussed, in the context of a managerialist culture concerned with performance and blame.

Participants found it difficult to identify any task not involving information sharing, confirming the view that information sharing is no longer just a "part" of safeguarding work but has become "the" work. Practitioners discussed the need for clear facts on which to base decision making. This required practitioners to be skilled and tenacious in obtaining information and communicating it, both verbally - to families - and in writing, such as case file recording and court documents.

The depth of information sharing

All tasks, from receiving the referral through to decision making and court proceedings, were loaded with emotion and anxiety, including:

- Frustration, when referrals were received late and with missing information, resulting in children being left in potentially dangerous situations;

- Fear and anxiety around giving evidence in court;

- The dynamics of working with people who may mislead or be intimidating;

- Joy and satisfaction when a family managed to change or an assessment was completed well.

A further complexity related to workers managing their reactions to information about abuse. Practitioners spoke of using instinct and emotion to help them understand a case. These responses were accepted as valuable sources of intelligence, vital to gaining an accurate understanding of what was happening for families. Thompson (2010) says such "emotion information" needs to be substantiated by factual evidence, bringing depth concerns to the surface. Practitioners gave striking examples of knowledge that began as instinctive, which they managed to surface and articulate in case work.

Implications for practice

These findings highlight practice and information sharing as both rational and emotional and identify the challenge in the requirement for "emotional information" to be shared and recorded within rational frameworks. Where this is done inconsistently this can result in teams and agencies developing an understanding of a case based on different information and differing interpretations of whether or not an intervention threshold has been met.

Lees concludes by suggesting:

- Increased acknowledgement of the dual nature of information

- Practice development in order to use "emotional information" to service users' benefit

- Training in information sharing to emphasise the emotional aspects alongside technical-rational instruments such as flow charts

- Shadowing and shared learning opportunities to explore others' roles

- Psychoanalytically informed interventions such as the use of the case study discussion model (Ruch, 2007) or systems-centred therapy (for example, Agazarian, 1992).

STUDY 3

Internet Technology: An Empowering or Alienating Tool for Communication between Foster carers and Social Workers?

Jane Dodsworth, Sue Bailey, Gillian Schofield, Neil Cooper, Piers Fleming, and Julie Young, British Journal of Social Work, (2013)

Foster carers and social workers are increasingly expected to embrace information and communication technologies (ICT). This article reports on the introduction of a purpose-designed internet service, to enhance interaction and information exchange between foster carers and social workers, provide a secure social networking facility for communication between carers and create the potential for a fostering community forum.

In 2009, the Digital Inclusion Team, funded to implement the Inclusion Through Innovation Report by the Social Exclusion Unit, commissioned an independent evaluation of the implementation of the fostering internet service within three authorities in England.

Key findings from the research included:

- Carers felt that the internet service was not integrated into social workers' practice, that social workers were too busy and that too few staff used the service to make it an accepted method of communication. Carers preferred sending emails, as they knew social workers "check e-mails first thing", or text messages as "people can't ignore a text".

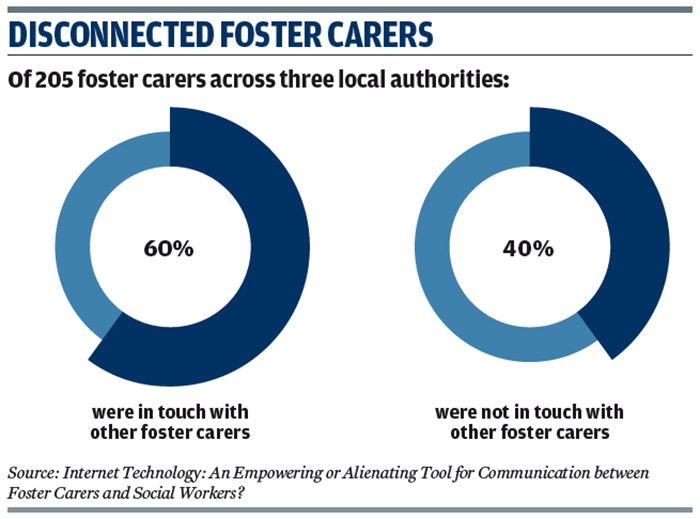

- Only 60 per cent of the 205 foster carers were in touch with other foster carers through any means. A total of 40 per cent reported that they were not in touch with other foster carers and some stated that they had neither the time nor inclination to do so. This latter group clearly did not perceive that they were in any way part of a "community of fostering practice".

- Those foster carers who had contacted other carers did so for practical and emotional purposes: to arrange car shares, suggest excursions, discuss paperwork, to "off-load", seek or offer support and chat.

- Booking training courses via the website was popular in all three authorities.

- Perceived concerns around confidentiality prevented wider use of an electronic daily log facility, indicating a need for further monitoring and review of systems, but also for ongoing support and training for carers to increase confidence in, and awareness of, the level of confidentiality built into the internet service.

- The message board was used to provide, rather than request, information and the information tended to be oriented to task communication rather than socio-emotional content.

- The exchange of information and views and the potential for increased foster carer knowledge and participation was perceived as threatening by those social workers, who felt less technologically competent than some foster carers.

- Some carers stated they fostered because they liked children and that an overemphasis on standards and qualifications, or a requirement to become IT proficient in order to foster well, could act as impediments. Other foster carers were willing to use all the resources, including IT resources, available to them to foster as effectively as possible.

Similarities in internet use

There were some marked similarities in the factors that either impeded or facilitated the implementation and subsequent use of the fostering internet service.

The first factor was the degree to which carers owned, or whose local authority provided, computers and had access to a broadband connection.

The second was the degree to which both carers and staff were computer literate, had sufficient training and ongoing support to use the online site and were open or resistant to the use of ICT in a fostering context.

Third, whether the council promoted the idea of some carers being encouraged to be ‘champions', providing peer support by and for carers, was significant.

A fourth factor was whether carers and social workers were accessing rather than sharing knowledge through the website, being passive rather than active participants of this virtual fostering community.

A consideration arising from the findings was whether a system could be developed in relation to certain tasks, such as secure file transfer, for those wishing to use it in this way, when others were unwilling or unable to take this up. Strategies were needed for foster carers who, either through resistance or lack of ICT connection, were excluded from information and opportunities that were available to other carers and for social workers who were resistant or unable to embrace new technologies.

Implications for practice

While recognising the limitations of a small-scale evaluative study, it is notable that the findings echo themes identified in other studies in terms of agency and social workers' and foster carers' perceptions, concerns and hopes regarding the use of ICT, suggesting a need for further research on the wider issue of power relationships between foster carers and social workers and the part technology can play in empowering carers and enhancing their professional standing.

STUDY 4

Technology Configuring the User: Implications for the Redesign of Electronic Information Systems in Social Work

Philip Gillingham, British Journal of Social Work, (2016)

Electronic information systems (IS) used in child protection services have been strongly criticised in England (Munro 2011) and Australia as presenting "substantial obstacles to good practice". Understanding the problems is crucial to redesigning IS in ways that support rather than hinder frontline practice. In this article, based on ethnographic research in four Australian and two English organisations, examples of how technology has impacted on social work practice are analysed.

Changes to practice - information gathering

Due to the fact that IS can store more information than paper files, the temptation can be to record as much detail as possible on the premise that mining it in the future may provide previously hidden insights. In one organisation, this included information which was passed verbally between staff and required all practitioners involved to take time to enter information into the system.

However, compelling practitioners to record information just because they can may not be constructive as social workers develop ways to manage information to meet their practice needs, such as persisting to share information verbally only. Information systems also affect the shape of recorded information, for instance by encouraging practitioners to predetermine and categorise information using tick-boxes or dropdown lists. This "jigsaw" approach to gathering information is limited because meanings and values are not fixed and building a picture of a child's life is a process requiring ongoing analysis of the information.

Changes to priorities - servicing the IS versus service users

Participants estimated that they spend 60 to 80 per cent of their time engaged with IS and the study explored the reasons for this concerning pattern.

One participant reflected that on returning to work after a 20-year gap they felt like no one was trusted to do their job anymore as everything had to be recorded on the IS. If it was not recorded, it was as if it had not been done - even if recording took twice as long as the activity. This participant also reflected that technology had made it possible for frontline practitioners to do tasks previously undertaken by administrative staff. In interviews with younger staff, many, though not all, complained about the amount of time they spend servicing the IS. This might mean that some did not resent this way of working, accepted it and/or had adapted to it.

Social work practice and priorities have been "configured" through interactions with IS. In particular, the balance of time spent on interacting with service users as opposed to IS has shifted, with the potential to jeopardise the central goal of social work - engagement with people in supportive interventions.

Implications for future IS design

Problems identified in social work practice and with IS are interlinked. However, while IS have reconfigured social work practice, changes in IS design will not automatically lead to improvements in practice.

Implications for practice

New approaches to practice are difficult to embed into IS. In current designs, social work activities are modelled procedurally, as if all the variables in a situation can be predicted and planned for. For example, in an initiative to promote relationship-based practice, it might be possible to build into an IS expectations that social workers spend a certain amount of time with a service user. However, specifying this time in advance is no use to social workers who are aware that it is quality rather than quantity that counts in building supportive relationships and that the time required to do so will vary from one service user to another.

With these considerations in mind, a strategy for addressing these challenges involves:

- Reversing the process of social work practice being configured by technology by developing a clear vision of how improvements to practice can be made, which can then inform the redesign of IS.

- Putting this vision at the heart of participatory design, with the functionality of IS directly benefiting practice initiatives and practitioners directing designers, rather than the other way around.

- Evaluating new IS in terms of their effects on social work practice, specifically the extent to which they support and promote practice improvement initiatives; ethnography is an effective method.

FURTHER READING

Related resources:

- Eliminating unnecessary workload associated with data management, Report of the Independent Teacher Workload Review Group, March 2016

- Multi agency working and information sharing: Final Report, Home Office, July 2014

- A divergence of opinion: how those involved in child and family social work are responding to the challenges of the Internet and social media, Child and Family Social Work, December 2013

Related resources by Research in Practice:

- Social media: opportunities as well as risks for frontline practice: Strategic briefing, 2017

- Social media: opportunities as well as risks for frontline practice: Recorded webinar, July 2016

- Enabling effective contribution of health partners to safeguarding: Leaders Briefing, 2014

- Multi agency working: Research and Policy Update, September 2015