Narrowing the Attainment Gap: Policy context

Derren Hayes

Thursday, November 29, 2018

Each year, the Department for Education publishes a range of data showing how well schools and local authorities have met attainment benchmarks at different stages of a child's education.

It also publishes data on the socio-economic gap in attainment in the early years, at key stage 2 and key stage 4. This data can be complex to navigate, but a number of think-tanks and research organisations analyse it to give a clearer picture of the education opportunities available to children from different socio-economic groups.

Over the past two years, pupil attainment has risen, according to data generated by the National Pupil Database.

The Early Years Foundation Stage Profile shows that 71.5 per cent of children achieved a "good" level of development in 2018, a 0.8 percentage point rise on 2017. The figure has been improving consistently since 2012, when 51.7 per cent of children achieved a good level of development.

At KS2, 64 per cent of pupils reached the expected standard in reading, writing and maths, according to provisional figures published in July 2018. In 2017, 61 per cent of pupils met the expected standard in reading, writing and maths, and in 2016, 53 per cent did.

At KS4, the proportion of pupils achieving the grade 4 target on the new 1-9 scale - equivalent to five GCSE grades A-C - was 69.2 per cent in 2018, up from 68.7 per cent in 2017. The proportion achieving good marks in English and maths also rose.

Why the attainment gap is important

The attainment gap is the term that describes the difference in achievement between disadvantaged pupils and their better-off peers. This is measured at key points throughout their education journey. The DfE defines "disadvantage" as pupils who are eligible to receive pupil premium funding - those who have been eligible for free school meals at least once in the previous six years. The gap measures how far behind disadvantaged children are in terms of academic achievement compared to their peers.

Education can have a transformative effect on the life chances of young people, enabling them to fulfil their potential and have successful careers. As well as having a positive effect on the individual, good quality education also promotes social mobility and economic productivity. However, data shows disadvantaged children do less well in education, with research showing this can hinder their life chances, and the economic and social development of the country.

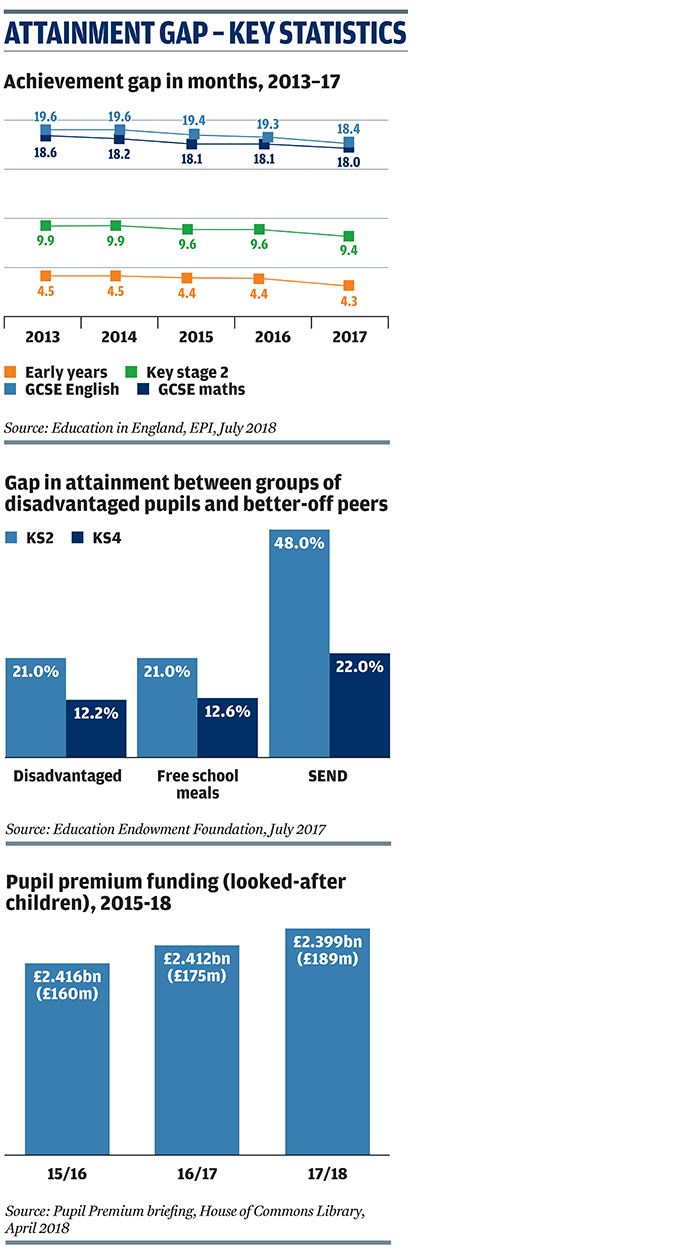

Analysis by the Education Endowment Foundation (EEF) measures the attainment gap in reading, writing and maths for pupils with a range of disadvantage characteristics. Its 2017 report, The Attainment Gap, shows children with special education needs and disabilities (SEND) experienced the widest gap at both KS2 (48 per cent) and KS4 (22 per cent) of any other group of pupils (see graphic).

Meanwhile, research published by the Education Policy Institute (EPI) in July shows the average attainment gap in reading and maths grows as disadvantaged pupils progress through the school system - at age five, the gap is 4.3 months; at age 11 (KS2) the gap is 9.4 months; and by age 16 (KS4) the gap is 18 months (see graphic). For persistently disadvantaged pupils - those in receipt of free school meals for 80 per cent of their school lives - the attainment gap is even wider.

The EPI's analysis reveals that the gap has fallen year on year since 2011 across all age measures - however, it points out that at the current rate of progress, it will take 100 years for disadvantaged pupils to achieve the same level of attainment as their peers.

When analysed by region, the development gap at age five is highest in parts of Merseyside and Yorkshire, while Oldham, Halton and Rochdale have recorded low attainment in KS2. The fastest growing gap between early years development and KS2 attainment is in the Eastern region.

At KS4, Blackpool, Coventry and Derby have low attainment levels. Meanwhile, authorities in the North East are seeing the fastest growth in the low attainment between KS2 and KS4 - in Northumberland, the attainment gap is 11.3 months at KS2 and 26.1 months at KS4.

However, some areas with high levels of disadvantaged pupils, such as Tower Hamlets (see practice example), have similar KS4 attainment levels as more affluent areas such as Surrey and West Sussex.

Policies to tackle the gap

There has been a steady stream of government initiatives and policies aimed at improving the attainment of disadvantaged children over the past decade. Programmes such as the Opportunity Areas have focused on improving access to high-quality early education for families in economically deprived communities. Other policies, such as the introduction of virtual school heads, have targeted more support at looked-after children; one of the groups at most risk of struggling academically.

The pupil premium

The introduction by the Liberal Democrat and Conservative coalition of the pupil premium in 2011 has coincided with the narrowing of the attainment gap. In 2017/18, around two million children received a share of £2.4bn of pupil premium funding. Primary schools receive £1,320 per child and secondary schools receive £935 per child registered as eligible for free school meals.

From 2018/19, schools also receive £2,300 for every pupil on their roll who is either in local authority care or adopted.

In addition, early years settings receive a premium of £300 for each disadvantaged pre-school child attending sessions, and a similar amount goes to schools where a child has a parent who is in the armed forces.

The funding, which has been guaranteed in cash terms until 2022, is used to pay for additional support to be put in place to boost the attainment of disadvantaged children. It is worth on average £81,000 per primary and £168,000 per secondary. Schools decide how to spend the money, but have to publish information on the impact it has had.

The EEF has produced a teaching and learning toolkit on how to use the premium effectively, and an evaluation tool to help schools measure the impact of their approaches.

Author and education expert Matt Bromley says the pupil premium has been effective in closing the attainment gap in areas with the highest concentration of disadvantaged children. But in schools with low numbers of pupils receiving the premium, the gap has actually widened over the same time.

EEF analysis published this year shows that at 19 per cent, London has by far the lowest attainment gap of any region when measuring pupils in receipt of free-school meals. The next lowest is the West Midlands at 26.3 per cent. The report states that London's success is likely down to a mix of factors, "notably improvements at primary schools from the late 1990s, initiatives in secondary schools and an influx of pupils from high-attaining immigrant families" (see Research Evidence).

However, a 2015 report by the National Audit Office found that while the pupil premium had the potential to bring about "significant improvement in outcomes for disadvantaged children", more needed to be done to "optimise value for money". The same year, the Commons public accounts committee said the DfE needed to be better at "supporting schools to share and use best practice so that schools can use the premium effectively". And in 2017, the Social Mobility Commission called for greater consistency in how councils used the premium so that funding is invested in evidence-based practice.

Bromley attributes the variable success of the premium in closing the gap to a number of factors. First, children in receipt of free school meals are not the most educationally or socially disadvantaged - "50-75 per cent of free school meals pupils are not in the lowest income households", he says. Second, the size of the attainment gap in individual schools is influenced by how well more advantaged children do in assessments. "The more advantaged the non-pupil premium cohort are, the harder it is to close the gap," he explains. However, Bromley says there are measures school leaders can take to ensure they get the most out of the premium (see expert view, below).

Early years focus

Ministers and DfE policymakers have recently targeted support at pre-school children in deprived areas. In September 2017, government-funded childcare was extended to 30 hours per week, and since 2014, the 40 per cent most deprived children have been eligible for 15 hours of funded childcare. However, analysis this year by the Early Intervention Foundation found this had only "modest" improvements on children's educational outcomes.

The 2017 Social Mobility Action Plan included measures to improve the skills of childcare practitioners to close the "word and numeracy gap" for disadvantaged children. Local authorities have received £8.5m to review and improve the early language and literacy support they provide for disadvantaged children.

The action plan also builds on the 12 social mobility Opportunity Areas. The £72m, three-year programme is being delivered in Blackpool, Derby, North Yorkshire coast, Norwich, Oldham, West Somerset, Bradford, Doncaster, Fenland and East Cambridgeshire, Hastings, Ipswich and Stoke on Trent. The areas are to be measured on whether social mobility improves, but this could take up to 15 years.

In August, Education Secretary Damian Hinds announced measures to inject more academic rigour into the early years, with £30m made available for schools in deprived areas to develop nursery facilities, and £45m to create partnerships between schools and councils, multi-academy trusts (MATs) or charities to boost early child development.

Another important programme is to develop, test and implement innovative ideas to create a local welfare system that has child development at its heart. A Better Start is a £215m, 10-year Big Lottery Fund programme that aims to improve outcomes in social and emotional, language and physical development in the first three years of a child's life. The five areas to receive funding are Blackpool, Bradford, Lambeth, Nottingham and Southend (see practice example), which will be implementing changes up to 2025.

Many of these national initiatives involve early years organisations, with some developing their own projects, such as the National Day Nurseries Association's Maths Champions programme (see practice example), and Easy Peasy, a 20-week home learning project (see research evidence).

Boosting attainment in schools

Many of the government's social mobility programmes include measures to help schools tackle the attainment gap. For example, the Social Mobility Action Plan includes measures for high performing teachers to work in the most deprived areas, better use of evidence-based teaching practices, and improving post-16 training options. Many of the Opportunity Area action plans outline targets to improve numeracy and literacy in schools, and careers advice.

Less than half of children in care achieve good results in English and maths, compared to around three-quarters of their non-care peers. The introduction of virtual school head teachers in every local authority has helped sharpen schools' focus on looked-after children's education, and the additional support they may need to achieve. There are signs that having a senior educator monitor the progress of looked-after children and hold schools to account for their achievement is resulting in improved performance in some councils. For example, in Wolverhampton, the number of care-experienced children going to university has quadrupled since 2014 (see practice example).

The substantial increase in the pupil premium plus in 2018/19 should also help schools and virtual heads further improve support and narrow the attainment gap in the long term.

ADCS VIEW

Do more to help children in care achieve

By Debbie Barnes, director of children's services, Lincolnshire County Council, and chair, ADCS educational achievement policy committee

As corporate parents, we aim to offer the same level of support and challenge for children in care as we would for our own. However, as a country, we can do more to improve their outcomes; education is key to improving life opportunities and it is vital that we do all we can for children in care to help them overcome difficult early life experiences, such as trauma, neglect or bereavement.

Being in care is not in itself damaging to children and young people's life chances, and it is important that we continue to push this narrative. A study by the universities of Oxford and Bristol point to a strong association between the length of time a child spends in care and positive educational outcomes aged 16 and beyond.

Children in care are likely to progress in education in a way that is different to their peers and it is important that we recognise this. Difficult early life experiences can mean that progress takes a little longer, especially as many enter the care system in adolescence, meaning that we should take a long-term perspective. GCSEs are not always the best indicator of attainment for everyone and there are many other skills and qualities that are equally important to help them reach their future potential. The importance placed on these exams is huge, yet for many 16-year-old children in care, this can be far too soon. We need to look at progress measures rather than raw attainment, and provide teachers with the appropriate training and support to better understand and meet their needs.

Closing the attainment gap has long been a focus of the educational achievement policy committee. Alongside the National Association of Virtual School Heads and the National Consortium of Examination Results, we launched the Children Looked After Analysis Project in 2016 to help all those working with children in care set ambitious but appropriate educational targets and assist with the provision of support to meet these targets via better use of pupil premium funds.

Schools must do all they can to help children in care achieve better-than-expected progress by providing the support they need to achieve to their capability. In a context of reduced funding and an accountability system that prioritises academic attainment, the stakes are high for school leaders who wish to adopt inclusive approaches, so it is imperative that the government allocates additional resources where needed for schools to further support these children.

CHILDCARE VIEW

Early years pupil premium is a missed opportunity

By Melanie Pilcher, quality and standards manager, the Pre-school Learning Alliance

No one doubts the importance of the early years in narrowing the attainment gap - and politicians from across the political spectrum all talk a good game about wanting to see it close completely. But all too often the conversation starts with admitting that something must be done, only to end without any action. That is perhaps why there was so much fanfare for the early years pupil premium (EYPP) when it was first announced.

The policy was introduced by the coalition government in April 2015 to support three- and four-year-olds from disadvantaged backgrounds. Its potential was immediately obvious: it focused resources on those young children who had the most to gain from a quality early education, promising to narrow the gap between those children and their peers.

But has it delivered? The initial honeymoon period produced plenty of effective and innovative uses of the new funding. Purchasing materials and resources to develop home learning packs for parents to support their child's learning at home were all well-received early examples. Beyond those first few green shoots, it's been difficult to track its impact.

The only out-and-out evaluation of EYPP so far has been the January 2016 SEED report, conducted during its first academic year. This identified a number of teething issues: payments taking so long that children had left the provision before the funding came through, and comments from providers frustrated with the additional administration required to claim and monitor impact on an ongoing basis.

Ofsted inspection reports should be able to provide consistent monitoring. It's concerning, therefore, that the use of EYPP has been mentioned in just 40 of 27,017 reports of childcare on non-domestic premises and just two of 38,962 childminder inspections. Those are stark figures - and it's difficult to know what to make of them. Is it simply that providers are missing an opportunity to demonstrate positive impact? Or Ofsted are less interested in inspecting it than other areas? Or is it, more worryingly, that providers are not using the premium whatsoever?

There is at least one good reason why interest in EYPP may be flagging a little - many feel funding is too low to have a significant impact. A 2016 Social Mobility and Child Poverty in Great Britain State of the Nation report argued the funding should be increased to at least half the amount (£604) eligible to primary school pupils.

The statistics are clear: the attainment gap is narrowing. What's not clear is why that is. The EYPP seems like a good vehicle for targeting support where it is most needed, but without proper evaluation we simply don't know. Without that knowledge, getting across its value to practitioners and parents is impossible.

EXPERT VIEW

The pupil premium can still help schools narrow the attainment gap

By Matt Bromley

On average, 40 per cent of the overall gap between disadvantaged 16-year-olds and their peers has already emerged by the age of five. These gaps are particularly pronounced in early language and literacy. By the age of three, more disadvantaged children are, on average, already almost 18 months behind their more affluent peers in their early language development. Around two-fifths of disadvantaged five-year-olds are not meeting the expected literacy standard for their age.

The premium should, therefore, be spent on improving children's literacy and language skills. Black and William (2018) explain: "Children from working-class families, who are only familiar with the restricted code of their everyday language, may find it difficult to engage with the elaborated code that is required by the learning discourse of the classroom and which those from middle-class families experience in their home lives."

Daniel Rigney, in his book The Matthew Effect, adds: "While good readers gain new skills very rapidly, and quickly move from learning to read to reading to learn, poor readers become increasingly frustrated with the act of reading, and try to avoid reading where possible. Pupils who begin with high verbal aptitudes find themselves in verbally enriched social environments and have a double advantage."

Isobel Beck (2002) devised a three-tier system to help teachers decide which words to teach to help the disadvantaged catch up. Tier 1 words are the basic and high frequency words that are used in everyday conversation; tier 2 words appear more frequently in written language than in spoken language, and used by language users of different ages; and tier 3 words relate to specific fields of knowledge, such as the sciences.

Beck argues that teachers should explicitly teach disadvantaged pupils the tier 2 words they need to access the curriculum. She shares a sequence for teaching these words:

- Read the sentence in which the word appears aloud to the class

- Show pupils the word written down and ask them to say it aloud

- Ask pupils to repeat the word several times

- Discuss possible meanings with the class

- Point out any parts of the word that might help with meaning, for example a prefix or Greek or Latin root

- Reread the sentence to see if there are any contextual clues

- Explicitly explain the meaning of the word through simple definition and the use of synonyms

- Provide several examples of the word being used in context, emphasising the word

- Ask questions to determine whether or not pupils have understood the word

- Provide some sentences for pupils to judge whether or not the word is used correctly

- Get pupils to write their own sentences using the word

- Explicitly use the word over the next few days in order to reinforce its meaning.

Matt Bromley is an education journalist and author with 20 years' experience in teaching and leadership including as head teacher. He is a consultant, speaker and trainer, and the author of numerous best-selling books for teachers including "Making Key Stage 3 Count", "The New Teacher Survival Kit" and "How to Learn"

www.bromleyeducation.co.uk

FURTHER READING

Education in England, EPI, July 2018

School Cultures and Practices: Supporting the Attainment of Disadvantaged Pupils, Government Social Research, May 2018

The Attainment Gap, EEF, January 2018

Social Mobility Action Plan, HM Government, December 2017

Closing the Gap, EPI, August 2017

Unlocking Talent, Fulfilling Potential, DfE, 2017

Divergent Pathways, EPI, July 2016

Funding for Disadvantaged Pupils, Commons public accounts committee, October 2015

Funding for Disadvantaged Pupils, NAO, June 2015