Legal Update: Children's overnight stays in cells

Kirsten Anderson

Tuesday, February 4, 2014

Thousands of children spend a night in police detention before appearing in court. Kirsten Anderson, legal research and policy manager at Coram Children's Legal Centre, examines the law on detention.

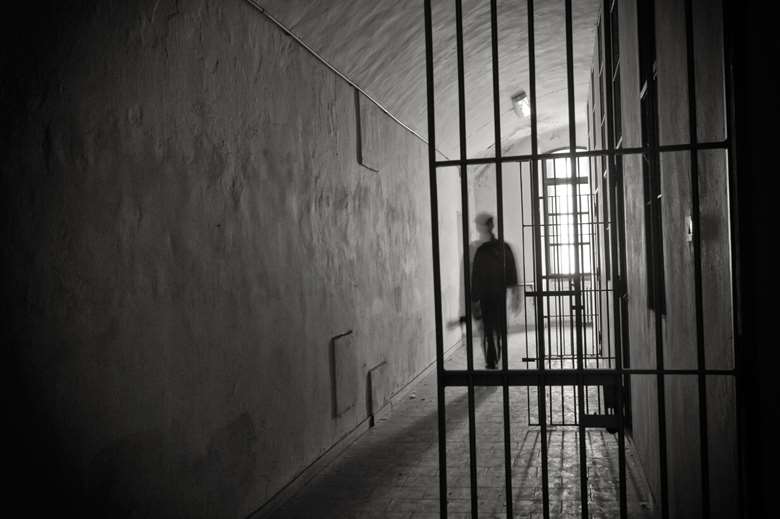

Research by the Howard League for Penal Reform has found that 40,716 children under the age of 17 were held overnight in police cells in 2011. This included 2,292 children aged 10 to 13. Even a one night stay in a police cell can be a frightening and intimidating experience for children, particularly for young children, and detention should be strictly used as a last resort measure, appropriate in only a very small number of cases. The statistics on the number of children in police detention, however, indicates that it is a regular occurrence.

Law on the use of police detention

The government has obligations in international law to protect and fulfil the rights of children who come into conflict with the law, including children who have been arrested and subject to the possibility of police detention. Article 37(b) of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child provides that "no child shall be deprived of his or her liberty unlawfully or arbitrarily", and that "the arrest, detention or imprisonment of a child shall be in conformity with the law and shall be used as a measure of last resort and for the shortest appropriate period of time". Also, the UNCRC provides, in Article 3, that, in any decision affecting a child, their best interests shall be a primary consideration.

The most significant domestic laws relating to police detention are the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 (Pace) and the Pace Codes of Practice, in particular Code C, which concerns detention, treatment and questioning of people by police, with specific provisions relating to children. According to these laws, a child can only be held in police custody for up to 24 hours in most circumstances. Police custody should cease when a decision is made by the custody sergeant or Crown Prosecution Service that there is not enough evidence to charge them. Even where there is sufficient evidence, a child can be released on police bail. Generally, there is a presumption that a child will be released on bail without conditions. Children can be released from police custody back into the care of their parents or guardians, or, where appropriate, into the care of the local authority.

Where children are refused police bail, there is a statutory duty on police and social services to refer the child to non-secure local authority accommodation, unless this is not practicable. Where the offence is serious, a child over 12 can be referred to secure accommodation. The data indicates that only a small number of children are refused police bail. Police officers should only refuse bail where the offence is particularly serious; the child's address or name cannot be ascertained; if there are reasonable grounds for determining that the child will not attend court as required; where it is determined that they may commit further offences if granted bail; or where they will harm persons or property or interfere with the administration of justice if released. Police may also refuse bail where it is in the child's "own interests".

Despite this, it appears that police are detaining children overnight for minor misdemeanours which could be resolved outside the criminal justice system. It has also been found that children are being needlessly held overnight, not in accordance with these criteria, but to fit in with police processes, or due to delays or staffing issues. They also appear to be being detained for "their own protection". The research found, for instance, that 15 per cent of the total number of overnight detentions in 2010 and 2011 were girls, which is significant given that girls represent less than five per cent of children receiving criminal sentences. This is thought to reflect a heavy-handed, protectionist approach by police, who indicate that they take girls into custody for their own protection, for instance, when they are intoxicated.

The practice of detaining children overnight in police cells does not appear to meet with international standards. Children should be detained in police custody overnight only as a matter of last resort.