Inspections Clinic - Workforce stability Q&A

Jo Stephenson

Tuesday, July 28, 2020

Research highlights the link between a stable workforce and better outcomes for children. Ofsted’s Yvette Stanley tells Jo Stephenson how it is assessing workforce stability across children’s social care services

Ofsted’s most recent annual report highlighted concerns about staff turnover in children’s social care. Yvette Stanley, the regulator’s national director for social care, answers key questions on trends in workforce stability before lockdown measures were imposed.

Is high staff turnover an issue inspectors are increasingly picking up during visits?

Local authorities and their staff are under a great deal of pressure because of Covid-19. Staffing levels will have been affected in lots of areas. I’m in no way criticising these places – they are doing the best they can under very difficult circumstances. Local authorities really are at the sharp end of managing local responses to the virus and we’ve been so impressed with how they’ve risen to the challenge.

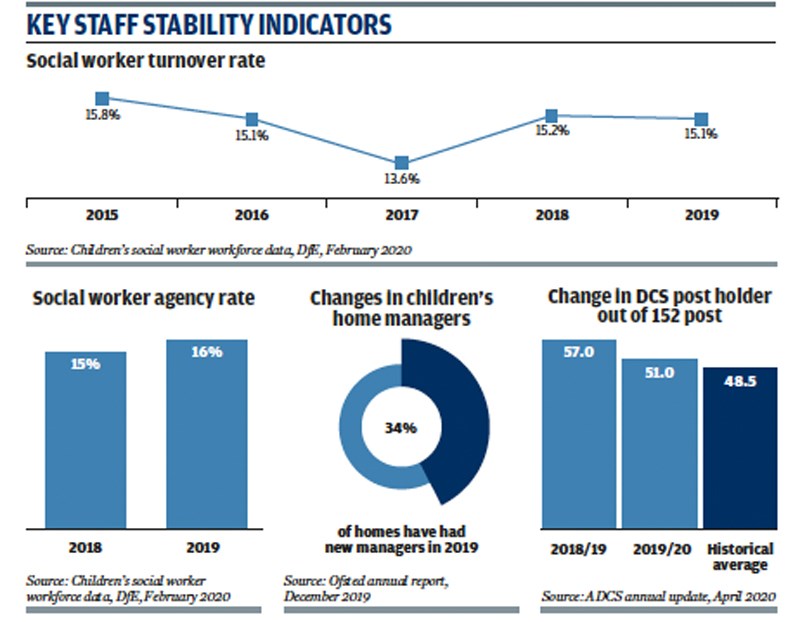

However, if we look back to a time before the pandemic and before we suspended our routine inspections, problems with staff retention do tend to be a common issue in weaker councils. Over the past two years, when we have inspected local authorities previously rated “inadequate” or “requires improvement”, slightly more than half have clearly been struggling with high staff turnover. When we have inspected previously “good” or “outstanding” local authorities, almost all report good staff stability.

Does high staff turnover also mean the quality of carer for children is poorer?

High staff turnover doesn’t automatically mean services and outcomes for children are less good. There may be instances where – in the short term – local authorities are mitigating any impact on children. That said, where staff turnover is a long-standing problem that hasn’t been addressed, it’s hard to see how this isn’t going to have an impact on the help and care children are getting. While a stable workforce is desirable and an over-reliance on agency staff can be an indicator of weakness, many agency staff are effective practitioners and can make a positive contribution to vulnerable children’s lives.

Is it a particular problem in some services such as children’s residential care and secure provision?

We see secure training centres experiencing the greatest challenge in terms of staff stability. Difficulties in recruiting and retaining staff are consistent features in secure children’s homes that are less than “good”. Staffing problems in secure training centres are long-standing and we have reported our concerns about the lack of staff skills and experience to care for children appropriately. Turnover is still a challenge in children’s homes, including filling registered manager posts, which is a critical role. Our latest annual report noted fairly small, but ongoing, increases in staff turnover in the last four years.

What are some of the consequences of high staff turnover observed by inspectors?

Long-term problems with staff turnover are going to lead to instability and, in turn, the quality of services for children will likely deteriorate too. It manifests itself at all levels. High turnover of leaders, such as several directors of children’s services – or council leaders and chief executives – in rapid succession is going to mean unstable leadership, which will ultimately feed down into frontline practice. There’s unlikely to be an effective line of sight about what’s happening on the ground, little continuity, and a risk of losing momentum on the things that are actually working.

If you have a high turnover of social workers or other frontline staff, this is going to have an enormous impact on the rest of the team, in terms of workload and high caseloads.

There’s a likelihood of using more agency staff, many of whom do an excellent job – but can’t be relied upon as a long-term solution. Some areas end up in a situation where poor practice is being tolerated, just because managers are grateful to have staff in post.

If caseloads are changing hands all the time, children and families aren’t going to have that single point of contact who knows their particular issues. They aren’t going to be able to build up meaningful relationships.

What is Ofsted’s sense of some of the factors that drive high staff turnover?

Undoubtedly, high caseloads, staff shortages and poor working conditions play a role. We often talk about local authorities creating “an environment for good social work practice to flourish”. Where this doesn’t happen, we’re likely to see councils struggling to hold on to staff. We know that low caseloads allow for more focused and higher-quality direct work with children. Social workers need to know families and know them well if they are to really make a difference. The variation between local authorities in the numbers of children per social worker is too wide – caseloads range from working with seven to in excess of 30 children.

What kind of things do Ofsted inspectors do and look at to understand workforce stability?

Staff turnover data is a starting point. It poses lines of enquiry for inspectors rather than assisting with forming inspection findings and judgments. Inspectors will spend time understanding the factors that encourage social workers to continue to work for their employer, or lead to staff leaving or being disinterested in applying to work for the agency or council. We evaluate the effectiveness of management oversight of practice, including the quality and effectiveness of supervision. Another factor social workers tell us about is the effectiveness of the local model or approach and the extent that working with risk is shared with their leaders.

What are the best authorities doing to address high staff turnover?

Newly-qualified social workers value effective social work academies – or equivalent set-ups – which help to determine appropriate caseloads before they work with higher risk families. Broader workforce development opportunities are important – for example, where practitioners choose not to advance to managerial positions. High-performing local authorities tend to have career progression opportunities through roles such as senior or advanced practitioner, who hold the more complex cases – in relatively small numbers – while providing ongoing professional support to less experienced colleagues.

Are there any common failings in areas that are not doing so well on staff turnover?

Lack of support and career progression opportunities, poor physical working conditions, a lack of corporate ownership of children’s services, poor IT systems and, although not always a deal breaker, pay can be a factor.

What role does the director of children’s services and other senior managers have in this?

Critical – this is why the inspection of local authority children’s services (ILACS) system now makes a judgment on the impact of leaders on practice with children and families.

Information correct at the time of going to press. Check www.ofsted.gov.uk for updates

INSPECTIONS SHORTS

EDUCATION

Inspection reports are being published by Ofsted again after this was put on hold due to the coronavirus pandemic. The publication of reports from recent inspection was paused, but some were released at the request of schools, further education and early years providers. The regulator confirmed all reports that had not yet been published would be released before the summer holidays. The publication of some management information was paused in April, but this is also due to re-start.

SOCIAL CARE

Ofsted has said it will fast-track applications to register new children’s home places urgently needed as a direct result of the pandemic. The regulator has set up a temporary fast-track application process open to local authorities and existing private and voluntary providers that can show they have been commissioned to provide places by a local authority. The move is among other temporary changes to the registration process for social care provision.

EARLY YEARS

Ofsted has restarted visiting new early years and childcare settings that have applied to join its register. Registration visits were put on hold due to the Covid-19 crisis, but have now recommenced for those with applications at the “ready for a visit” stage. Meanwhile, the regulator has urged settings to keep it informed about their opening hours including temporary closures and decisions to re-open provision.

HEALTH

Staff have been urged to speak up if they have any concerns about the quality and safety of health and care services amid the pandemic. The Care Quality Commission said it was “more important than ever” that staff felt confident – and were supported – to report any issues. The regulator has created a new monitoring tool – the Emergency Support Framework – to help it understand the impact of Covid-19 on staff and people using services, and identify when it may need to inspect or escalate concerns to partner organisations.

YOUTH JUSTICE

Swift action by the prison service has helped prevent the spread of coronavirus among inmates with fewer cases than feared, according to the prisons inspectorate. However, there has been concern about the impact of restrictions on the wellbeing of prisoners, including young offenders. Short scrutiny visits to young offender institutions earlier this year revealed wide variation in the amount of time young people were able to spend out of their cells.