Domestic Abuse: Policy context

Derren Hayes

Monday, April 29, 2019

The Crime Survey for England and Wales estimates that there were 1.2 million female and 713,000 male victims of domestic abuse in 2016/17, respectively 7.5 and 4.4 per cent of the total population.

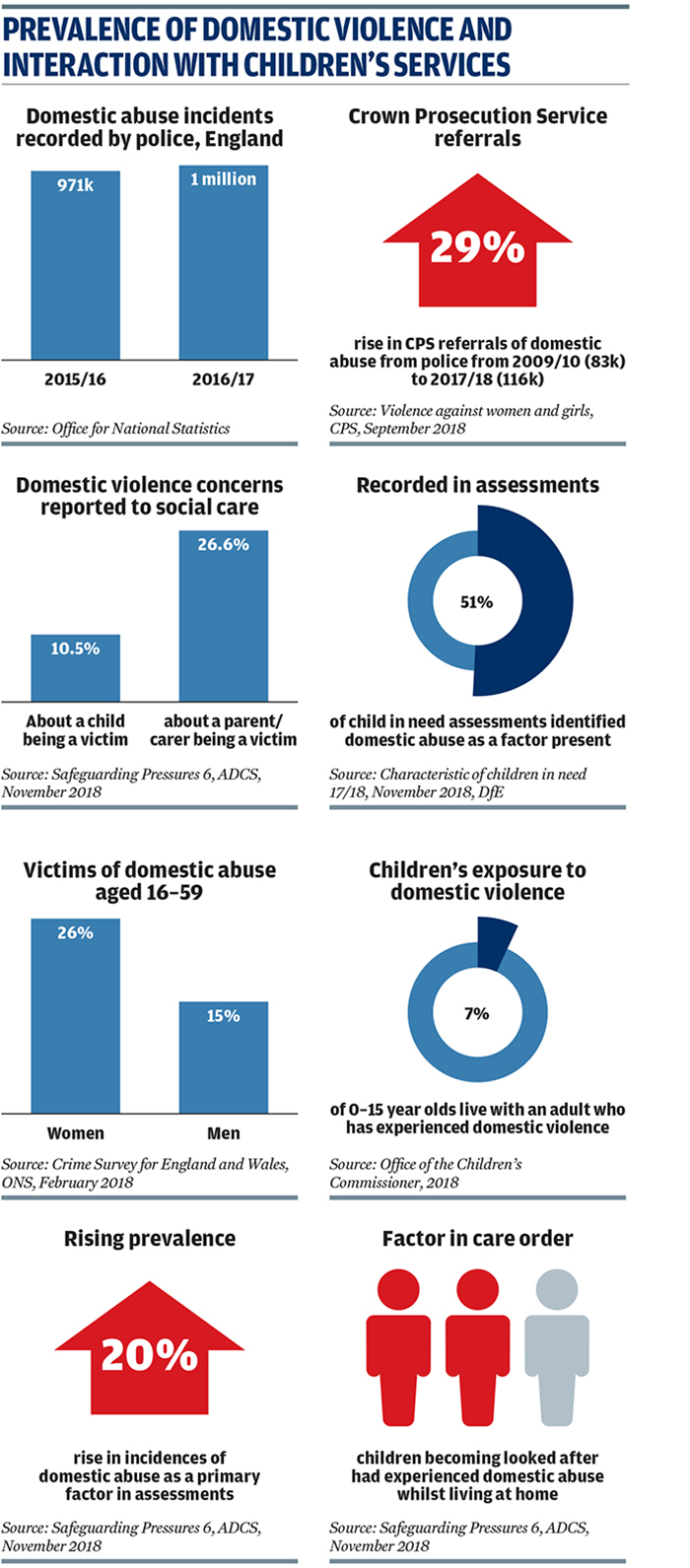

The survey also finds that 26 per cent of women and 15 per cent of men had experienced domestic abuse between the ages of 16 and 59.

Police recorded crime data suggests there has been a significant rise in domestic abuse over the past decade. In 2008/09, there were around 750,000 incidents recorded by the police, but by 2016/17 this has risen to just over one million incidents. There has been a year-on-year rise every year since 2007, however how data is collected was changed in 2015 making annual comparisons difficult. Despite this, there was a three per cent rise in reported incidents over the 12 months to March 2017.

While the number of cases of domestic abuse being recorded by police has risen, there has been a gradual decline in the number of referrals made to the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS), from a high of around 120,000 in 2014/15 to 116,574 in 2017/18. However, this is still 29 per cent higher than the levels recorded in 2009/10.

Most recent CPS figures reveal the number of prosecutions fell six per cent in the past 12 months as did the proportion of referrals that led to charges being laid - 69.1 per cent down from 70.7 per cent in 2016/17. However, this was still significantly higher than levels recorded a decade earlier.

In 2018, the children's commissioner for England reported that 825,000 children aged under 16 live with an adult who has experienced domestic violence, and that more than 100,000 children are living in a family with the so-called "toxic trio" of domestic violence, parental mental health problems and alcohol or substance abuse present.

Research published last year by Jane Callaghan et al found that such abuse affects children's relationships and curtails their ability to express themselves due to fear that saying the wrong thing could result in abusive incidents (see research evidence).

A report by Pro Bono Economics last year also estimated that up to one in five children that witness domestic violence are are at risk of developing an emotional or behavioural disorder as a result. Data from the Office for National Statistics also suggests that older teenagers are at greatest risk of being victims of domestic abuse - 7.6 per cent of 16 to 19 year olds had been the victim of abuse by a partner or ex-partner over the previous 12 months.

In its response to the domestic abuse consultation, also published in January, the government explains the rationale for the broad definition of domestic violence used in the draft bill. It states: "Domestic abuse does not only occur between couples. It can also involve wider family members, including parental abuse by an adolescent or grown child. It can exist between older siblings, or the wider extended family in elder or honour-based abuse.

"Domestic abuse involves many different acts and behaviours. We recognise that a simplistic description may fail to completely encompass the dynamics of power and control, and the risk that control represents to the victim."

POLICY RESPONSE

The draft Domestic Violence and Abuse Bill published in January has been drawn up following a consultation held in 2018 that sought views on addressing four key prevention focused objectives: promoting awareness among professionals and the public; enhancing protection and support for victims; improving how the justice system deals with perpetrators, including identification and rehabilitation; and improving the consistency of performance among agencies and areas in how they respond.

It provides the first statutory definition of domestic violence. The new definition in the draft bill applies to relationships between two people aged 16 and over who are "personally connected". It defines behaviour as abusive if it consists of any of: physical or sexual abuse; violent or threatening behaviour; controlling or coercive behaviour; economic abuse; psychological, emotional or other abuse; and conduct towards a third party, such as a child, that affects a partner.

The draft bill also sets out a series of measures the government will take to tackle the issue. These include:

- Establish the Domestic Abuse Commissioner

- Provide for a new Domestic Abuse Protection Notice and Domestic Abuse Protection Order

- Prohibit perpetrators of domestic abuse cross-examining victims in person in the courts

- Make Domestic Violence Disclosure Scheme guidance statutory

- Introduce new duty on councils to provide secure lifetime tenancies for social tenants affected by domestic abuse.

Statutory guidance to accompany the definition of domestic violence will expand further on the different types of abuse and the forms they can take. This will include types of abuse which are experienced by specific communities or groups, such as migrant women or ethnic minorities and also teenage relationship abuse. This will also recognise that victims of domestic abuse are predominantly female.

The government says the statutory guidance will also "recognise the devastating impact that domestic abuse can have on children who are exposed to it" and "ensure that agencies are aware of it and how to appropriately identify and respond". The guidance will apply to all statutory and non-statutory service providers to help improve consistency of practice across the country (see research evidence).

The Ending Violence Against Women and Girls Strategy 2016-20 was published by the Home Office in March 2016. It consolidates action taken by the government to tackle stalking, forced marriage, female genital mutilation, revenge pornography, and coercive or controlling behaviour.

The strategy's vision is that by 2020:

- There will be a reduction in the number of victims of violence against women and girls (VAWG) through an improved criminal justice response and perpetrator support.

- Greater priority of earlier intervention and prevention across all services.

- Specialist support made available for the most vulnerable victims.

- More interagency working across local areas to spot victims

- Women will be able to disclose experiences of violence to all public services.

- Stronger emphasis on protecting VAWG victims through evidence-based practice.

Over the three-year Spending Review period up to March 2020, the government has pledged £80m of dedicated funding to support refuges and other accommodation-based services, a network of rape support centres and a network of national helplines.

In November 2018, 63 projects were allocated a share of the £22m Domestic Abuse Fund over two years. The money will be given to councils to pay for the creation of an additional 2,200 beds in refuges and other safe accommodation, improve access to education and training for survivors, and provide life skills support. Recipients include Slough Council, which is working with social housing provider Hestia, and Portsmouth City Council which is working with charity Stop Domestic Abuse to boost home security measures (see practice examples).

The £8m Children's Fund, announced alongside the draft bill, is funding nine projects that support children under 18 that are affected by domestic violence. Interventions range from awareness raising in school through to one-to-one therapeutic support. One project in Stockport is to place independent domestic violence advisers in hospital maternity wards and ante- and post-natal clinics (see practice example).

In April 2017, the VAWG Transformation Fund was created with £17m to "support and embed local best practice" across 41 areas.

Last November, the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government published updated statutory guidance that requires councils to prioritise victims living in refuges and other temporary accommodation for social housing places. The guidance states that it is "important that victims of domestic abuse who are provided with temporary protection in a refuge…are given appropriate priority under a local authority's allocation scheme, to enable them to move into more suitable settled accommodation, releasing valuable refuge spaces for others". The guidance also urges councils to ensure domestic abuse victims seeking social housing are not turned away through local residency tests when leaving another area.

IMPACT ON CHILDREN'S SERVICES

For a number of years, children's services leaders have been warning about rising domestic violence referrals. The Association of Directors of Children's Services' (ADCS) Safeguarding Pressures 5 report, published in late 2016, highlighted how in some areas the prevalence of the "toxic trio" of domestic abuse, parental mental health problems and substance misuse had reached "epidemic proportions" - in the Eastern region it was present in 90 per cent of all child protection cases.

Safeguarding Pressures 6, published by the ADCS last November, showed domestic abuse referrals had continued to rise in 2017 and 2018 - 26 per cent of all concerns about children's wellbeing related to a parent or carer being the victim of domestic abuse and a further 10 per cent about a child being a victim of it. Councils reported a 20 per cent rise in domestic abuse being the primary factors in assessments, while two out of three children taken into care had experienced domestic violence.

Despite the rising tide of domestic abuse-related work being undertaken in children's services, the ADCS points to cuts in early help funding and services as curtailing their ability to intervene early to stop abuse and provide the support victims need. The association says the funding attached to the draft bill is insufficient to develop the system-wide approach needed to properly tackle the issue and is calling for the government to develop a cross-departmental strategy to take this forward (see expert view, below).

That domestic abuse features so prominently in the everyday work of child protection teams, has seen some councils develop their own bespoke approaches to tackling the issue. One such example is Doncaster Children's Services Trust, which in 2015 received £3m between from the DfE's Children's Social Care Innovation programme to develop its Growing Futures pilot. The approach - which brings together health, social care, education and the voluntary sector - has since been embedded into practice, with an evaluation demonstrating that it has cut the number of families re-referred for domestic abuse (see research evidence).

Another example of a local initiative is Operation Compass, which sees police alert schools about children who live in households where a domestic abuse incident has been recorded. Initially developed in Gateshead, the scheme is to be rolled out across England and Wales thanks to a £163,000 grant from the Home Office.

A similar approach has been developed separately in Stockport where a "team around the child" helps link up universal services and children's social care to improve identification of families affected by domestic violence and ensure children affected by this receive support (see practice example).

Many authorities commission voluntary organisations to provide support services to victims or domestic abuse and their children. Women's Aid's annual audit of domestic abuse 2019 found that on 1 May 2018, there were 219 voluntary providers delivering 363 local services listed on the Routes to Support database. These ranged from refuge, resettlement, community support, prevention and education, and support for children. The number of services supporting children and young people had grown by by around four per cent. The audit shows the number of refuge bed spaces had gone up slightly over the year, however Women's Aid calculates that there are still significant shortfalls in all areas of England bar London.

Extrapolated data from the audit reveals that 136,000 referrals were accepted by community based voluntary providers and 12,000 by refuges. However, six in 10 referrals to refuges were declined, 17 per cent due to lack of space. The figures serve to highlight to policymakers how service capacity - in terms of prevention, child protection and voluntary sector refuges - needs to increase to meet the rising demand in the system.

ADCS VIEW

DOMESTIC ABUSE IS A PUBLIC HEALTH ISSUE

By Rachel Dickinson, president, Association of Directors of Children's Services and director of children's services, Barnsley

The Home Office published new research at the start of the year which estimated that domestic abuse collectively cost the criminal justice system, civil and legal services, social care, housing and health services a staggering £66bn in 2016/17. The human costs are incalculable.

Domestic abuse continues to be the most common factor in children's social care assessments, this includes children themselves being the subject of domestic abuse, witnessing a parent being abused or concerns about another person in the household being subject of abuse. It is one of the main factors in re-referrals too.

Domestic abuse factored in all cases from all categories of serious and fatal maltreatment in the latest triennial review of serious case reviews, which warned that our incident-led responses increase the likelihood of exposure to harm continuing for extended periods of time.

Both the triennial review and Ofsted have reinforced the view that in tackling this issue we must maintain a strong focus on early help and prevention. However, as local authority budgets continue to fall, we find ourselves cutting the very services that help us to intervene early and stop abuse.

In recent years we have moved away from thinking about domestic abuse as a private family matter or a police matter to treating it, rightly, as a serious safeguarding concern. Experiencing parental conflict and domestic abuse can have a lifelong impact on children and young people's mental health, their educational attainment and the success of their own future relationships. Concerted action - and funding - is needed to ensure they can access emotional, psychological and practical support when and where it is required to break generational cycles of trauma and abuse.

We welcome a renewed focus on domestic abuse, yet the government's plans, and the accompanying £20m funding, do not reflect the scale, reach or severity of this issue. The Draft Domestic Abuse Bill seeks to increase reporting but the necessary support services for perpetrators, victims and their families are lacking after a decade of austerity.

A collaborative, cross-government strategy for tackling domestic abuse is urgently required. This should seek to raise awareness, enable more effective identification and provision of support at the earliest possible opportunity and, crucially, prevent domestic abuse taking place. A national public service campaign to tackle public attitudes whilst deterring perpetrators is overdue and should be at the heart of a public health approach to turn the tide on this silent epidemic.

EXPERT VIEW

CHILDREN MUST BE INCLUDED IN VICTIM DEFINITION

By Emily Hilton, senior policy officer, NSPCC

According to Department for Education statistics, up to 259,000 children are currently living in households with domestic abuse, but due to the hidden nature of this type of violence there will be countless other children suffering in silence.

Children may not feel able to talk to their teacher or their youth worker about these issues, they may not even understand that what they are experiencing isn't normal or healthy. We know from talking to young people like Luke and Ryan Hart, whose mother and sister were murdered by their father, that children can also be victims of domestic abuse even when it is directed at parents.

When the government released the draft Domestic Violence and Abuse Bill in January, I was hopeful that children living with domestic abuse would be recognised and supported. But I was surprised and disappointed to see that when it came to the statutory definition of "who is a victim" children were notably absent. Currently, there is no legal recognition of the day-to-day distress that living with domestic abuse creates or the complex trauma children experience.

By failing to finally, officially recognise children as victims in law, the government is missing a crucial chance to give young people an extra layer of protection.

Long-term effects

Growing up in households with domestic violence affects everyone and can have a long-lasting impact. Children living with this abuse can be at serious risk of physical harm and are three times as likely to experience abuse or neglect themselves. Long-term effects can include mental health problems, difficulty forming relationships and aggressive behaviour.

By recognising children living with domestic abuse as victims in law, it would ensure not only that children are protected, but also that the services that support victims of domestic abuse also specialise in catering to the needs of children.

Throughout the stages of this bill we will continue to lobby government and politicians to recognise that abusive relationships between parents or carers cause children direct harm and can have a negative impact on them throughout their lives.

We urge them to rethink their statutory definition of victims to help ensure agencies can better work together to prevent children being exposed to domestic abuse, identify children at risk and help children recover so they do not suffer long-term effects.

EXPERT VIEW

WE NEED A STEP CHANGE IN OUR RESPONSE TO CHILDREN EXPERIENCING DOMESTIC ABUSE

By Amna Abdullatif, child and young people's officer, Women's Aid

Recently, we have seen an increased understanding about the harm domestic abuse causes children of all ages, including the significant impact that it can have on their emotional wellbeing, their school life, and their future relationships. Previously, assumptions were made that babies and pre-verbal children are unaware of violence and abuse that is taking place in their home and that the impact domestic abuse has on them is limited. However, this is not the case. Recent research shows that children who have experienced domestic abuse as babies can have more negative outcomes than older children.

It is important to remember that children are strong and resilient. They develop coping strategies to deal with the trauma they have experienced and, with the right support, can overcome the negative impact that domestic abuse has had on their lives, particularly with an early intervention response.

Yet despite the serious implications that experiencing domestic abuse at the home has on children, there is not adequate support or enough funding in place to address these issues. Our latest report, The Annual Audit: The domestic abuse report 2018, revealed that 1 in 15 survivors accessing domestic abuse support services are pregnant and nearly 60 per cent have children. Yet due to the ongoing funding crisis facing domestic abuse support services, many services are struggling to meet demand from survivors and their children and provide the level of support that they desperately need.

The importance of specialist services is paramount for the safety and wellbeing of children and their mothers. Yet there has been a significant fall in the number of specialist services that support children and young people in England since 2010. Some organisations are even running their children and young people services without any secure form of funding, highlighting the increased funding uncertainty these vital support services are facing.

Alongside the University of Stirling, Women's Aid has developed an early years toolkit, focusing on the impact domestic abuse has on babies and pre-verbal children and parenting, to help practitioners provide a needs-led response to both mothers and their children.

For far too long, children's experiences and needs have been ignored. We need a step change in our response to children who are experiencing domestic abuse - our toolkit provides one step forward towards bringing about that change. By recognising that children not only witness domestic abuse but also experience it, putting their experiences and their needs at the heart of our response, we can bring children from out of the shadows and make it everyone's business to support children experiencing domestic abuse.

- Women's Aid's toolkit from https://www.womensaid.org.uk/resources-for-children-and-young-people/

FURTHER READING

Domestic Abuse Report 2019: The Annual Audit, Women's Aid, March 2019

On the Sidelines: The Economic and Personal Cost of Childhood Exposure to Domestic Violence, Pro Bono Economics and Hestia, March 2019

Domestic Abuse Consultation Response and Draft Bill, Home Office and MoJ, January 2019

Safeguarding Pressures 6, ADCS, November 2018

Social Housing Allocations Statutory Guidance for Councils, MHCLG, November 2018

Domestic Violence in England and Wales Briefing Paper, House of Commons, November 2018

Are They Shouting About Me?, Children's Commissioner for England, August 2018

Domestic Abuse Fund, MHCLG, July 2018