Councils face increased pressure to respond to child refugee crisis

Adam Offord

Tuesday, January 19, 2016

Kent Council is struggling to cope with a major rise in the number of unaccompanied asylum-seeking children it is caring for, to the point where the government is preparing to force other authorities to share the burden.

The war in Syria and subsequent humanitarian crisis across the Middle East has seen an estimated one million people travel from the region to Europe over the past year, many of them children and young people either travelling with families or alone.

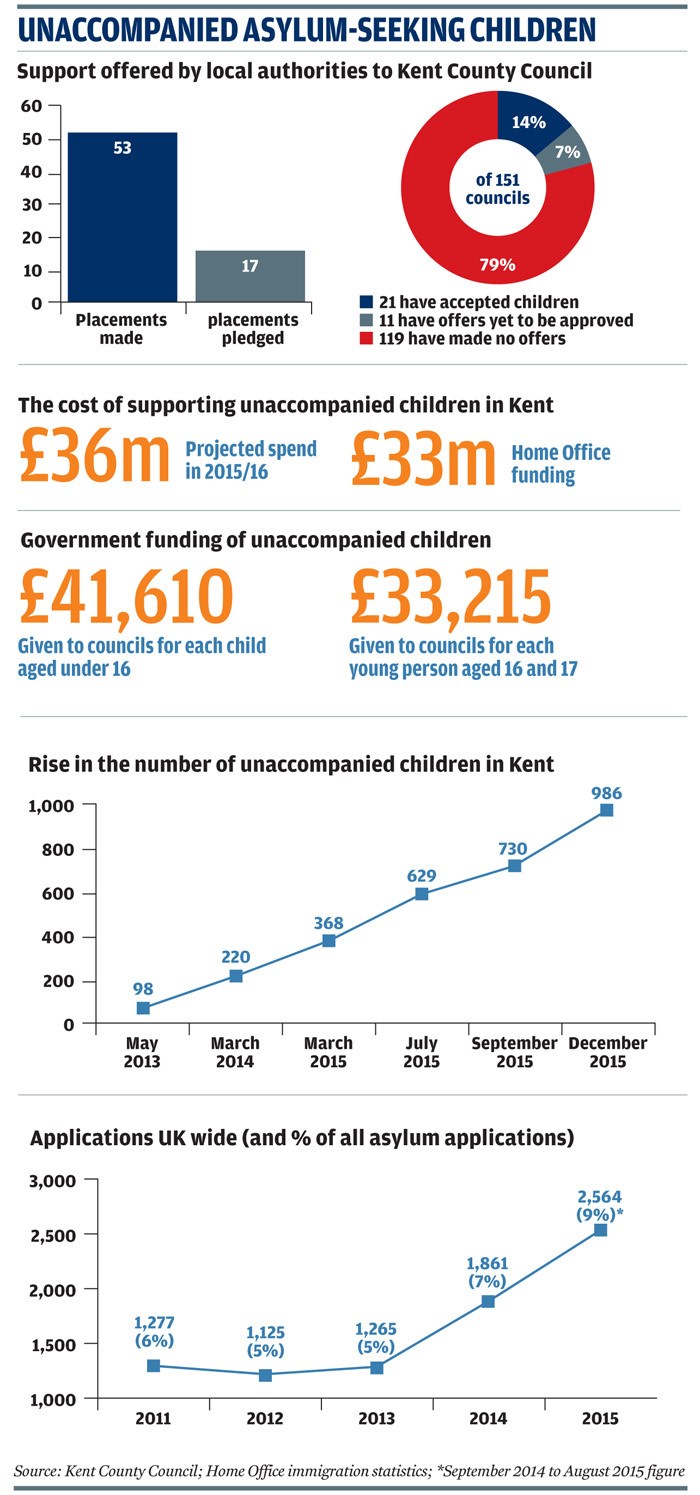

While most end their journeys in mainland Europe, some have entered the UK, mainly via the Channel Tunnel or cross-channel ferry services, coming to the attention of authorities when they first arrive in Kent. Under-18s travelling alone will automatically be placed into the care of Kent County Council, which has seen a 10-fold increase in the number of unaccompanied asylum-seeking children (UASC) it cares for over the past two years (see graphic).

The sharp rise has placed huge pressure on the council's children's services, as well as other public agencies such as police, education and health services, with the support bill expected to be £36m in 2015/16 (see graphic).

Last August, children's services leaders called on other councils to offer help to "overwhelmed" Kent and find placements for unaccompanied children.

However, latest Kent Council data shows just 53 UASC have been accepted and transferred to 21 local authorities across the country so far, with offers of 41 placements from 15 authorities being progressed (see graphic).

In a letter sent to all local authority leaders last month, government ministers said the level of response was "simply not enough". The government pledged to raise funding available to councils for offering placements for UASC - now, each child accepted from Kent aged under 16 attracts a payment of £41,610 per year, with 16- and 17-year-olds attracting £33,215 of funding each (see graphic).

National approach

The Local Government Association (LGA) says the inadequate funding levels may have been to blame for the low uptake, and wants the new rates to be implemented as part of a more co-ordinated national approach.

David Simmonds, chairman of the LGA's asylum, migration and refugee task group, says: "Supporting vulnerable children is one of the most important things that councils do, but it is not right that councils are left facing a significant financial burden when supporting these children.

"The government has recently boosted funding for children arriving in Kent in recognition of this shortfall, and it is vital that this arrangement is now extended into a properly funded national scheme to support all areas struggling with increased numbers of unaccompanied children."

Alison O'Sullivan, president of the Association of Directors of Children's Services (ADCS), agrees that a properly funded national scheme is needed to ensure vulnerable children get the best support possible. "There is a recognition this is a national issue and responsibility needs to be shared," she explains. "We need to do this in an organised way that is good for the young people."

O'Sullivan says that discussions with government are ongoing about how a national dispersal scheme for UASC could work.

However, a recent government amendment to the Immigration Bill could override these discussions. If adopted, it will give the Home Office the power to compel councils to accept UASC from other parts of the country if they cannot give a satisfactory reason why they cannot do so.

O'Sullivan says she is "puzzled" why the government felt the need to introduce compulsory powers when discussions are taking place.

But Peter Oakford, Kent Council's lead member for specialist children's services, says the authority wants to see government action so that it does not continue to shoulder the bulk of the responsibility.

Government scheme

"We would like to see some regulations and legislation brought in around this to make it a government scheme," he says.

Children's Commissioner for England Anne Longfield also welcomes the government's action. "The number of unaccompanied children who landed in Dover over the summer stretched the (Kent) authority's services to the limits, so it is vital that responsibility for caring for them is shared," she adds.

But she says the decision to move a child to the care of another authority must be done only when it is in their best interests.

"It is less likely to be in a child's interests to move them if they are already settled, particularly where they have education and legal representation in place," she says. "So I would like a limit on the time during which a child can be transferred across authorities so they can only be moved before they have settled."

Judith Dennis, policy manager at the Refugee Council, wants to see more help offered by authorities, avoiding the need for government action. "We were very supportive of the request from Kent for a voluntary arrangement," she says.

"We would rather it be voluntary as we don't want local authorities to feel like they're having children foisted upon them. But we have to support the fact that the needs of the children come first.

"I can see why the government feels the need to legislate, but I wish it wasn't necessary and hopefully it won't have to be invoked."

While the number of under-18 UASC in the care of Kent Council dipped from 986 to 932 between December 2015 and January 2016, the authority says this is due to a large number of children whose ages were unknown being assigned a date of birth of 1 January and so "turning" 18 at the start of the year. As a result, the number of UASC aged 18 to 21 has risen from 402 to 467 over the same period.

The number of child refugees coming into Europe looks set to continue to rise throughout 2016. National data shows a large rise over the past two years in UASC applications, with these accounting for nearly one in 10 of all asylum applications (see graphic).

Meanwhile, a report published this month by the Commons' international development select committee raised concerns about the plight of unaccompanied refugee children in Europe amid reports of people trafficking, and urged the government to back a Save the Children proposal to take on 3,000 additional Syrian child refugees.

Longfield supports the proposal: "They must be properly cared for and protected from further harm such as being forced into prostitution or the drugs trade."

O'Sullivan agrees. "It is right that we offer more help. There will be practical implications such as finding foster homes for them to live. But the willingness from councils will be there."

Refugee Council guide to meeting the support needs of unaccompanied asylum-seeking children

The trauma experienced by unaccompanied asylum-seeking children (UASC) means they have similar support needs as other looked-after children, says Judith Dennis, policy manager at the Refugee Council.

"They might know where their parents are or they might not," she says. "So there are a range of different circumstances prior to them coming to the country."

She says specialist services, such as therapeutic services, will also have a role to play in helping local authorities and their UASC. "Therapeutic services engage them because they might have had significant loss or anxiety about separation," she explains. "That need doesn't go away even if they're no longer anxious about their own family because often they will be anxious about what is going to happen to them while they're here. There is lots of extra stuff for them to worry about."

Dennis warns that councils have to "look beyond the obvious" because young asylum seekers can appear to be more resourceful than other children if they can do things such as cook and look after themselves, but there can often be unidentified and hidden needs.

"It's a bravado they've had to have because they've had very difficult journeys and sometimes will have had responsibilities back in their home countries that (other) children here might not have had, so that actually masks the vulnerability that exists for them."

UASC could have been exploited or sexually exploited she warns, which could create trust issues with adults. They could also experience "culture shock" when arriving in the UK and will need help when navigating through systems such as school and health issues.

She adds older children are often placed in shared housing without 24-hour support and local authorities should make sure the child is in the right placement and coping well, while foster carers and social workers need to encourage all UASC to make friends.

Dennis says specialist services can help social workers and foster carers to understand the asylum process. "Sometimes children don't know what they have to do through the asylum process, they just assume 'we're here, we'll be okay'. So having to answer questions about why they should stay can be troubling for them."

Dennis warns the biggest cost incurred to local authorities is the placement in terms of where the child is going to live and who is going to look after them. She explains UASC will also have practical needs such as clothes and arriving mid-term might mean they don't get into a local authority school and have to travel. But UASC "shouldn't need massive amounts more than most young people in the care system".