Children’s Mental Health Special Report: Policy context

Derren Hayes

Tuesday, April 27, 2021

In her annual State of Children’s Mental Health report published in February, then children’s commissioner for England Anne Longfield described the figures as “staggering” and “likely to have serious implications for children now and for their long-term prospects”.

DATA ON DEMAND

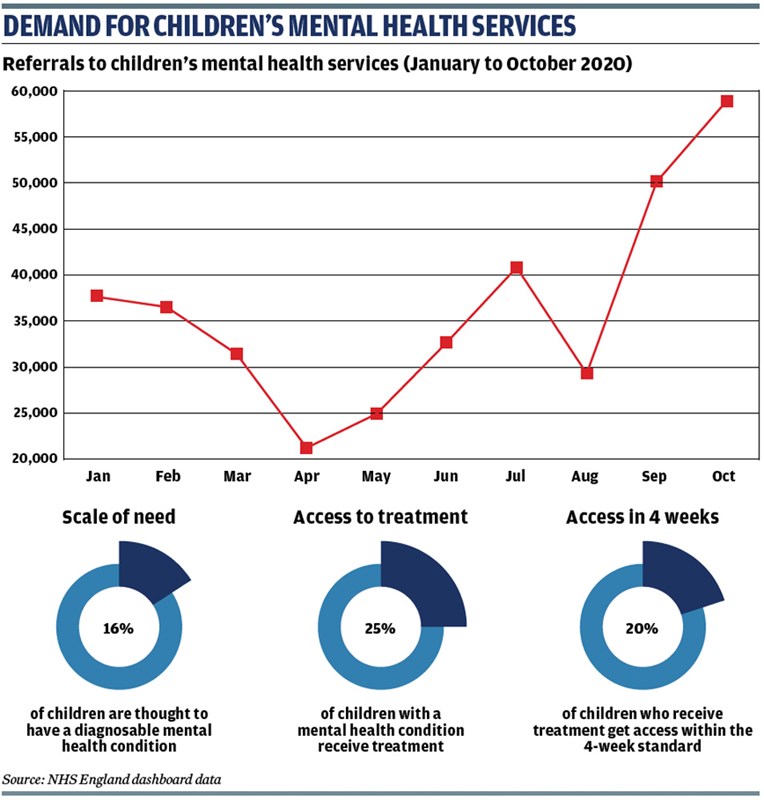

NHS data on children’s mental health services suggests the pandemic had a significant impact on the pattern of referrals for support. The data shows that between April and October 2020, the number of referrals tripled from 20,000 to 60,000, a third higher than at any point in the previous two years (see graphic). In April referrals were 34 per cent lower than in the same month in 2019, but in September they were 72 per cent higher than in September 2019.

Similarly, the number of children in contact with services fell during the first national lockdown and has only recovered partially since. It means that while referrals to services have rapidly risen above pre-crisis levels, the number of children accessing treatment has not. However, experts caution that numbers entering treatment fluctuates over the year, so it is too early to draw definite conclusions.

Many charities, research institutes and sector organisations have tried to assess the impact of the pandemic on children and young people’s wellbeing, some of which presents a contrasting and contradictory picture. For example, research for the children’s commissioner for England showed that overall the proportion of children feeling stressed fell during the first national lockdown, perhaps as a result of schools being closed to most pupils and less academic pressure. Conversely, a recent survey of 10,000 school staff by the National Education Union found that three quarters reported an increase in pupils’ mental health issues over the past year.

Meanwhile, findings from last year’s NHS Digital survey suggest that lockdown had made life worse for children and young adults with mental health problems compared with their peers with good mental wellbeing. For example, the proportion of 11- to 16-year-olds reporting life being harder during the pandemic was 54 per cent for children with a mental health condition compared with 39 per cent for those without.

Provisional data from NHS Digital shows that at the end of January 2021 there were 306,087 children and young people in contact with child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS).

ACCESS INDICATORS

Two key measures for assessing how children are accessing mental health services are how long they wait for treatment and the proportion of referrals that are rejected. Historically, CAMHS have not performed well on either measure. Although there has been a gradual reduction in waiting times over the past decade, this has coincided with a rise in rejected referrals.

The Children’s Mental Health green paper introduced a four-week standard for waiting times for referral to treatment at CAMHS. Research by the Education Policy Institute (EPI) published in 2020 found that the average waiting times in England far exceeded this standard in 2018/19. The EPI gathered data about NHS providers’ median and maximum waiting times from a child’s first appointment or assessment to treatment.

The average median wait for a child’s first appointment fell from 39 days in 2012/13 to 29 days in 2018/19, while the median wait to the start of treatment fell from 74 days to 56 days over the same period – both represent a reduction of around 25 per cent. London had the longest average waiting times for any region and the Midlands and East the lowest. According to the children’s commissioner’s analysis, 30 local areas have average waiting times of less than 30 days, but 34 areas have average waiting times of more than 60 days.

Average maximum waiting times to treatment have also improved over the decade falling from a peak of 761 days in 2012 to 451 in 2019. Over the same period, the maximum wait to a first appointment has also fallen from 508 to 335 days. However, there was a rise in both maximum waiting time measures – of 30 per cent and 25 per cent respectively – from 2017/18 and 2018/19.

Maximum waiting times represent one individual and are often influenced by extenuating circumstances outside of the provider’s control, for example due to a delay in accessing another NHS service such as a neurodevelopmental appointment. However, the EPI says that other reasons for long waiting times illustrate a system that does not work well for some vulnerable children and their families.

The report states: “Providers reported being unable to make contact, appointments being repeatedly cancelled due to staff and/or the young person being unwell, and patients not showing up to appointments. One provider reported a family being unable to attend appointments due to difficulty finding transport; in one case, an appointment cancelled due to staff illness resulted in the young person being seen two months later.”

Analysis by the children’s commissioner suggests that just four per cent of children accessed mental health services in 2019/20. Compared against 2017 levels of need, it suggests that just one in three children with a mental health problem received treatment last year – or one in four based on the 2020 projections of levels of need. Last year just 20 per cent of children referred to services started treatment within four weeks.

While access is generally improving, the commissioner highlights that services will need to expand more quickly if commitments in the 2019 NHS Long Term Plan are to be met.

NHS data shows that on average just over one in four referrals to CAMHS are rejected or deemed inappropriate, a rate that has remained roughly stable since 2015. Providers in London reported the lowest level of rejected referrals (16 per cent), with those in the South East reporting the highest (28 per cent). However, the EPI warns that CAMHS data is notoriously unreliable and highlights how the range of rejected referrals reported by each CAMHS provider grew last year, with some recording a rejection rate of 80 per cent and others zero.

It explains: “The way in which referrals are treated and categorised varies across providers; many who have adopted a ‘single point of access’ model – meaning all referrals go through an administrative triage process, and young people who are not admitted for treatment are signposted to another service – state that they no longer reject referrals, and therefore may report a very low proportion of rejected referrals.”

The NHS considers a child to be receiving “support” if they have two or more sessions. Based on this measure, 70 local areas close 30 per cent or more of their cases before children access support, a finding the commissioner describes as “disappointing”.

The government has pumped an additional £1.4bn into children’s mental health services since 2015, yet local funding decisions can still be a significant factor in how easy it is to access services. On average, local clinical commissioning groups spend less than one per cent of their overall budgets on children’s mental health – 14 times less than the amount spent on adult mental health services. Again, this varies by postcode, with children’s commissioner figures showing that eight areas spend less than £40 per child on mental health services, while 21 areas spend more than £100 per child.

ACTION TO IMPROVE ACCESS

This April saw every part of England covered by integrated care systems (ICS), which are new partnerships between organisations that meet health and care needs across an area, including councils and CCGs, to better co-ordinate services and to plan in a way that improves population health and reduces inequalities between groups. It is hoped that ICSs will bridge divisions between hospitals and family doctors, between physical and mental health, and between NHS and council services.

The NHS Long Term Plan confirmed all areas would be covered by an ICS from April and once their status has been established in law – NHS England has asked the government to implement legislative change – they will take over commissioning of children’s mental health services from CCGs. There are 42 ICSs across England, which have incorporated local sustainability and transformation plans, and many have involved community groups and the voluntary sector in drawing up priorities.

It is hoped that this more collaborative approach to planning, commissioning and delivering health services will improve access to CAMHS, particularly for certain groups such as young people from black, Asian and ethnic minority communities; who are gay, lesbian, bisexual or transgender; have special educational needs or disabilities, or are involved with children’s social care.

In its 2019 independent review of CAMHS in England, the Care Quality Commission highlighted a widespread lack of understanding of local need among providers. In 2020, the EPI found many CCGs and councils failed to fully engage with community and faith groups, despite these organisations potentially having a good understanding of the needs of groups underserved by CAMHS.

“Research has shown that mental health stigma is particularly strong in some minority ethnic faith communities; as such it is particularly important to understand how to engage these children and families,” the EPI report states.

Emerging evidence on the impact of the pandemic suggests ethnic minority communities are being disproportionately affected by unemployment and disruption to education. This, according to research carried out by the Centre for Mental Health, puts young black men at greater risk of developing mental distress due to the pandemic. The Innovation Unit is one organisation undertaking research in south London to better understand what support young people from deprived inner-city communities want to see available to help boost their mental wellbeing (see expert view).

ENTRENCHED NEEDS

Another group at risk of missing out on effective support are children and young people in the social care system. At least half of children in care have a diagnosable mental illness and up to 40 per cent have conduct disorder. Rising numbers of looked-after children overall and of those aged 10 and older – who tend to have more entrenched, complex needs – suggest demand on mental health services will increase over the next few years and will only be exacerbated by Covid (see ADCS view).

Evidence gathered by the EPI found some councils and CCGs offered specific services only for certain groups of looked-after children, for example those requiring Tier 3 (community specialist) interventions or those who had experienced three or more placement moves, while most reported that children in contact with social care could access general CAMHS.

“The concern is that this particularly vulnerable group of young people may lose out in a context where services are not effectively joined up or communicating regularly and effectively,” the EPI concludes. “We found that commissioning arrangements varied between areas, with some councils commissioning mental health services for children in contact with social services; in others, CCGs commissioned these services, or they were jointly commissioned by both agencies.”

Other measures to improve access have focused on boosting links between schools and CAMHS, such as the development of mental health support teams in schools – which the government plans to roll out to a fifth of all secondaries by 2023 – and community-based provision run by charities such as More than Mentors’ Community Links scheme. Some CCGs are also developing social prescribing initiatives that allow GPs to prescribe counselling and other support to young people with low-level emotional problems to boost wellbeing (see practice examples).

The children’s commissioner annual report backs the green paper’s vision for the future of children’s mental health services but warns the pace of change must be accelerated if it is to keep up with rising demand and children’s growing needs.

“The government must acknowledge that the provision of children’s mental health services is still nowhere near sufficient to meet children’s needs and ensure that they go beyond existing commitments with ambitious new targets to increase access to care,” it states.

ADCS VIEW TIME TO FOCUS ON VULNERABLE GROUPS’ NEEDS

By Charlotte Ramsden, ADCS president 2021/22

We have made progress over recent years to acknowledge and understand better the importance of good mental health for children and young people, yet there is much more to do before we achieve real parity of esteem. Covid-19 has been with us for over a year now and during that time, much of our focus has been on the physical impact of the virus, yet I have been encouraged by the development of a strong narrative on the importance of positive mental health, which has been a key theme throughout these challenging times.

It’s not surprising that the experiences of the pandemic have impacted the mental health of children and young people differently; while some have thrived spending more time at home outside the confines of the classroom, others have struggled with a lack of routine, social interaction and missed opportunities. Experiences have also been defined by circumstance; inequalities experienced prior to the pandemic have, in many cases, been further embedded within our communities. Previous research has also told us that those living in the most deprived areas in England are already 10 times more likely to be on a child protection plan or come into care than their wealthier counterparts.

As we plan for recovery and renewal, there is much focus and collaboration across the system to ensure mental health and wellbeing support is available to children who have been adversely impacted.

Accessing mental health services for children in care has long been an issue, especially when children are placed out of area. We know that the issues identified for children in care requiring support are the same reasons why services won’t engage; we can’t expect a child to be stable without putting in place the right support to help them achieve that. The NHS Long Term Plan identifies children in care as a vulnerable group and while the last 12 months have been dominated by Covid, I’m hopeful that with this recognition will come a new discussion about how we can prioritise the needs of children for whom we are corporate parents.

There are areas tackling these challenges head on, with colleagues coming together collaboratively across children’s services and health partnerships to recognise the barriers to access and build new approaches that better meet need. Setting out the commitment of leaders across an area to children in care, as corporate parents, is a strong message to deliver. There are also efforts under way to smooth the process of assessment and access for children in care who are placed outside of their local area, with supporting tariffs to reduce variation in the offer, facilitate multi-disciplinary working and most importantly, avoid delay for children and young people. Where local authorities and health partners are getting this right at the local and regional level, it’s important that we share this learning and encourage more areas to have these conversations. These are our children and we need to work together with shared aims and ambitions to make sure no one is left behind.

EXPERT VIEW YOUNG PEOPLE SET OUT POST-COVID PRIORITIES

By Daisy Carter, research co-ordinator, Innovation Unit

We spent a month collecting the lockdown stories of seven young people aged between 16 and 21 living in Lambeth to understand how the pandemic has affected their wellbeing and consider what they want to be put in place to help them. We also worked with a team of local young researchers to help us ask the right questions, make sense of our findings and bring their own lived experiences to strengthen our insights.

Our young people in Lambeth have, like many of their peers, grown up under austerity. Dramatic cuts to services enjoyed by previous generations have seen the loss of youth centres and other safe spaces to socialise with their friends and help build their confidence and emotional and mental wellbeing.

Many of our young people were transitioning to adulthood during this time, and experienced uncertainty around education routes, work opportunities, their own and parental income, a safe home.

Despite living complex lives, our young people found their own ways to survive and thrive: by connecting to their creativity, self-expression and spirituality; seeking community and mentorship; and embarking on their own entrepreneurial experiments.

Good mental health is about much more than a set of formalised services. Many of the young people we spoke to were not seeking mental health services, but practical help and resources to manage their lives; as well as sustained relationships with peers or mentors to help navigate their highs and lows.

We know that developing support for young people starts by understanding how young people frame their own “mental health” – which means listening to their views on what they think shapes their mental health and what they think will improve it. This framing, from the young people themselves, is what we should be focusing on, not the framing of professionals.

Our young people expressed the importance of connecting with people they trust – which meant access to devices and the internet as well as physical places that feel safe. As one said: “What you don’t want is youth centres with posters and hotlines on the wall…instead just have a nice place with great role models who give good advice.”

What the young people valued and what help they wanted begs the question: how do we involve young people from the start, and throughout, the process of designing mental health support rather than heading straight to formal programmes and services?

Already we’ve heard how mental health support for young people needs to be embedded in the places they feel safe and with people they trust to connect and empower them with opportunities that matter to them. Ideally mental health wouldn’t be something that gets dealt with “over there” for people who are really ill, but as part of everyday life.

Now we’re encouraged to “build back better” post-pandemic, let’s think about “designing forward differently” and ask: what will it really take to build communities that protect, support and listen to our young people; that are inclusive and ambitious about tackling the social determinants of mental ill health; and grow young people’s capacity to support themselves and others?