Mental Health in Schools: Policy context

Derren Hayes

Monday, June 24, 2019

For the past decade, policymakers have focused on using schools as a key setting to improve children and young people's mental health.

Targeted Mental Health in Schools (TaMHS) was a £60m programme, run from 2008-11, that aimed to provide early intervention and support for children aged five to 13 at risk of developing mental health problems, and their families.

By March 2011, up to 3,000 schools were delivering a range of TaMHS projects, with funding made available through the early intervention grant (EIG) provided by government.

The halving of the EIG since 2010 has seen many TaMHS projects fade away but much of the learning has been incorporated into local school-based mental health and early help support programmes.

Throughout the 2010-15 Conservative and Liberal Democrat coalition government, children's mental health continued to be a policy priority, with plans to boost provision in schools included in the 2011 strategy No Health Without Mental Health; 2014's Closing the Gap guidance; and 2015's Future in Mind taskforce report.

The government response to Future in Mind was to pledge £1.4bn to improve children's mental health services locally, including strengthening links between schools and child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS).

Since 2015, clinical commissioning groups (CCG) have been implementing Future in Mind reforms, although there has been criticism that some of the additional funding has been used to offset budget shortfalls elsewhere. In 2016, the Five Year Forward View for Mental Health also set out additional measures to improve children's mental health. The government's response included extra funding to train teachers in mental health first aid (see practice example) and plans to publish a green paper later in the year.

Children's mental health green paper

In December 2017, Prime Minister Theresa May delivered on her pledge to publish a green paper on children's mental health. The Transforming Children and Young People's Mental Health Provision Green Paper, published jointly by the Department of Health and Department for Education, set three priorities, two of which were school focused:

Incentivise every school and college to identify a designated senior lead for mental health to oversee the approach to mental health and wellbeing. All children and young people's mental health services would need to identify a link for schools and colleges. This link would provide rapid advice, consultation and signposting.

Fund new mental health support teams, supervised by NHS staff, to provide extra capacity for early intervention and ongoing help. Their work would be managed jointly by schools, colleges and the NHS. These teams would be linked to groups of primary and secondary schools and to colleges, providing interventions to support those with mild to moderate needs.

The government's response to the consultation outlined its intention to take forward all proposals in the green paper. In February this year, the DfE announced 370 schools would take part in a series of trials testing different approaches to supporting young people's mental health.

The trials, being run by the Anna Freud Centre and University College London, will test five different approaches: two focused on increasing awareness in secondary schools through short information sessions led by a specialist instructor or trained teacher; and three in primary and secondary schools focusing on light-touch approaches such as stress-reducing exercises (see below).

Another green paper initiative has seen NHS England lead on establishing 25 "trailblazer" sites to test mental health support teams. A total of 59 teams are to be set up in 2019 to develop models of early intervention on mild to moderate mental health issues such as exam stress, behavioural and relationship problems.

The teams will support school staff and act as a link between schools and CAMHS, building on the work of the DfE and NHS England Schools Link pilots which ran in 2015/16 in 255 schools in England.

Parliamentary scrutiny

The joint Commons education and health committee has undertaken two significant inquiries in the last two years on children's mental health. In 2017, its inquiry on the role of education in children and young people's mental health considered the co-ordination of support between health and schools, the success of early intervention and the impact of budget cuts.

The committee's subsequent report backed the government's policy direction, but raised concerns about the quality of links between health and education in some areas.

It called for Ofsted to properly inspect schools' approach to mental health and wellbeing, better teacher training on the subject - deficiencies on which had been highlighted by a survey of teachers earlier in the year (see research evidence) - and sufficient resources for the schools link pilots.

The committee followed this up last year with an inquiry into the green paper proposals. In the report, parliamentarians raised concerns about the timescales attached to the government's plans - saying the aim for mental health support teams to cover a fifth to a quarter of the country by 2022/23 "is not ambitious enough".

It also questioned whether having a designated senior lead for mental health in every school would place too much pressure on school leaders.

It also called for the government to assess the impact of exam pressure on pupils' mental health. Both criticisms were rejected by the government.

Rising demand, falling budgets

While government has invested in improving links between schools and specialist provision, there is growing evidence that tightening school budgets are unable to cope with pupils' rising support needs.

Latest research - drawn solely from government figures - from the School Cuts alliance shows that staff numbers in secondary schools have fallen by 15,000 between 2014/15 and 2016/17 despite having 31,000 more pupils to teach. This equates to an average loss of 5.5 staff members in each school since 2015; in practical terms this means 2.4 fewer classroom teachers, 1.6 fewer teaching assistants and 1.5 fewer support staff.

The reduction in pastoral support posts in response to budgets not keeping pace with rising numbers of pupils is making it harder for schools to identify and support pupils' mental health needs, says the Association of Directors of Children's Services (see expert view).

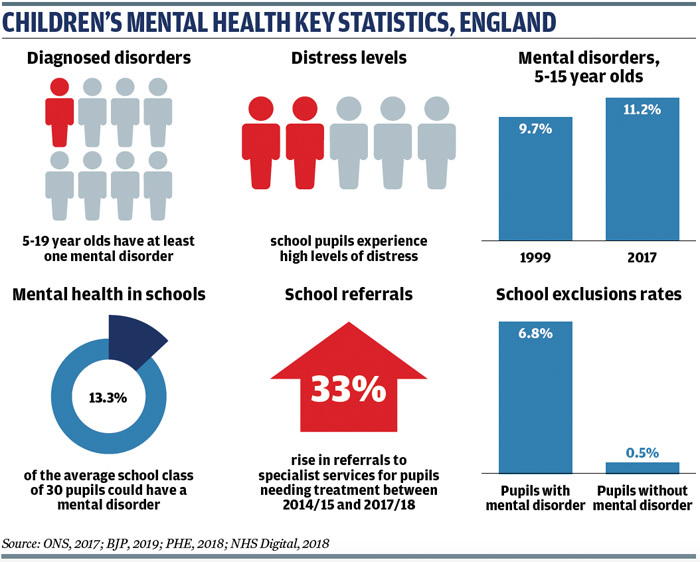

Unaddressed mental health problems can have a significant impact on children's education outcomes, warns Professor Sonia Blandford of Achievement for All (see expert view). This is illustrated by the fact that the exclusion rate for pupils with mental disorders is many times that of pupils without mental disorders (see graphics).

The bleak financial outlook in education comes at a time when research suggests pupils' needs are growing. Figures from the Office for National Statistics shows that one in eight children in the average class of 30 pupils has a mental health disorder.

Training for teachers and pupils

In January 2017, the government provided £200,000 to train 1,000 school staff in mental health first aid. The initiative, coordinated by Mental Health First Aid England, has been extended so that every secondary school in England will be covered by 2020.

Teachers and staff will receive practical advice on how to deal with issues such as depression and anxiety, suicide and psychosis, self-harm, and eating disorders (see practice example).

In 2015, the PSHE Association produced DfE-funded guidance on providing appropriate teaching about mental health problems, including lesson plans. Reforms to relationships and sex education (RSE) due to be introduced next year will build on this further.

Under the draft proposals, every school will be required to provide mental wellbeing lessons as part of health education.

In primaries, this will cover issues such as understanding and discussing emotions; the benefits of physical exercise; and loneliness. In secondary school, it will cover these issues in more depth as well as how to recognise the early signs of mental wellbeing problems; common types of mental ill health; and the positive and negative impact of various activities on mental health.

Ensuring mental health is on the agenda of staff and pupils alike is key to delivering the government's ambition for a whole-school approach to mental health.

Some schools, such as the Swanlea School in Tower Hamlets in London, are well ahead of the game, having incorporated mental wellbeing throughout the setting's culture (see practice example).

Other initiatives, such as the five-year £56m National Lottery HeadStart programme, are funding the development of community-wide approaches to children's mental health which include improving links between schools and other local agencies (see practice example).

These and other initiatives should ensure children's mental health is at the forefront of the schools agenda over the next decade.

EXPERT VIEW

Teachers with support can create mentally healthy schools

Green paper reforms need speeding up

By Rachel Dickinson, president of the Association of Directors of Children's Services

One in eight school children have an identified mental health condition, yet it is estimated around three quarters of young people experiencing mental health problems are not receiving the support they need.

We know that schools are often the best environment for early identification where teachers, school counsellors and learning support staff see children every day and can spot the signs of distress quickly. It has been encouraging to see the government's extra focus on this in recent years.

The 2017 green paper proposed the introduction of mental health support teams in schools which I am delighted to see. However, the government must be more ambitious; it is not enough for only a quarter of schools to have access to this new resource by 2023. We need a sustainable long-term funding strategy for children and young people's mental health that leaves no child at the mercy of a postcode lottery, especially as schools are facing their own funding pressures.

New relationships and health education guidance rightly made it compulsory for schools to teach pupils about good mental health and the importance of healthy relationships, but teachers must have the time and resource to deliver these important messages effectively.

A recent survey of 10,000 teachers conducted by the National Education Union found that 80 per cent believed mental health support had deteriorated over the past two years. Supporting children becomes even more difficult as the number of teaching assistants and pastoral staff, who are ideally placed to support those who need it most, has fallen due to budget cuts. It is essential that we give both teachers and headteachers the tools and support they need to help children overcome barriers to learning.

I worry that a school accountability system that values exam results above all else has exacerbated mental health problems. Exclusions are rising and there is real concern over the prevalence of "off-rolling" in some schools. Ofsted's new schools inspection framework is a welcome step to putting a stop to this practice.

We need a far more inclusive education system that puts the mental health needs of children ahead of performance tables.

Mental health and education outcomes

By Professor Sonia Blandford, chief executive, Achievement for All

The emotional wellbeing of a child or young person has a significant impact, not only on their mental health, but also their academic achievement and levels of progress.

Simply put, an anxious or angry mind will not learn.

Over the last 20 years, mental health has been a rapidly developing crippling disease, noticeably prevalent among the young - 90 per cent of school leaders have reported an increase in the number of students experiencing anxiety, stress, low mood or depression.

There are now three children in every classroom who have a diagnosable mental disorder. Recognising that an anxious or angry mind will not learn, teachers should be given the tools and language to have a conversation about a student's mental health.

Teachers are not experts and should recognise their limitations bridging the gap between their role and that of counsellors.

In many cases the need to enhance teacher's understanding of wellbeing can be addressed through continual professional development and ongoing coaching support.

Achievement for All has developed Achieving Wellbeing, a tried and tested evidence-based programme

The approach enables schools to accelerate progress for pupils by improving their emotional wellbeing and mental health. It is being delivered in 64 schools across England and Wales.

Trial to build evidence of what works in school mental health support

By Dr Daniel Hayes, Anna Moore and Dr Rina Bajaj, the Anna Freud Centre

With funding from the Department for Education, the Evidence Based Practice Unit - a partnership between the Anna Freud Centre and University College London - is leading the Education for Wellbeing Programme, one of the largest mental health trials of its kind in the world. This aims to give schools new, robust evidence about what works best for their students' mental health and wellbeing. The programme consists of two separate trials: AWARE and INSPIRE, which will work with around 25,000 pupils across England in 380 schools.

AWARE aims to implement and evaluate two universal mental health interventions with year 9 pupils in 150 secondary schools. Both interventions focus on improving pupils' knowledge and awareness around mental health, reducing stigma and encouraging help-seeking. Elements include:

- Youth Aware of Mental Health (YAM) is delivered in schools by external mental health professionals. Originally developed in Sweden and the USA, YAM has been adapted for a UK setting. It is a structured programme of five sessions involving group discussions and role plays.

- The Guide is delivered in schools by trained teachers. Developed in Canada and having been successfully implemented in Africa and South America, it aims to increase mental health literacy in pupils and staff and consists of six sessions delivered by trained teachers.

INSPIRE investigates three interventions in 160 primary and 70 secondary schools aimed at improving pupils' wellbeing. Schools are working with years 4, 5, 7 and 8 to evaluate approaches delivered by trained staff. These are:

- Mindfulness practices delivered for five minutes each day and consist of activities that focus on the body, the mind and the environment, in order to encourage pupils to be more present in the moment.

- Relaxation activities delivered to classes for five minutes every day. These involve deep breathing and muscle relaxation exercises.

- Strategies for Safety and Wellbeing draws on emerging practice in some UK schools around teaching practical approaches to personal safety. It consists of eight 45-minute sessions in which pupils explore the themes of risk, noticing early warning signs, when and how to access support and recognising the importance of support networks.

The programme will be evaluated using a mixture of survey data, focus groups and interviews with pupils and teachers. This will aim to examine if the interventions are effective - and cost effective - in improving mental health literacy and reducing emotional problems, and how pupils and staff have experienced the interventions.

Results will be available in July 2021 and it is expected that this research has the potential to transform mental health promotion in schools, giving teachers and other school staff information about what approaches work best and giving them the confidence to promote pupil wellbeing and support the children and young people they work with.

Applications for the 20 remaining spaces for Wave 2 secondary schools for AWARE are open until 5 July. More from www.annafreud.org/education-for-wellbeing/

FURTHER READING

- Transforming children and young people's mental health provision and government response to the green paper consultation, July 2018

- Health and education committee green paper inquiry and government response, May 2018

- Health and education select committees joint inquiry on children's mental health, May 2017

- Schools/CAMHS link pilots evaluation, DfE, Feb 17

- Mental Health Five Year Forward View, NHS England, February 2016

- Future in Mind, DHSC, March 2015

- Counselling in schools, a blueprint for the future, DfE, March 2015

- Targeted Mental Health in Schools evaluation, DfE, November 2011