Inspections: Early years provision in schools

Jo Stephenson

Thursday, May 4, 2017

Ofsted inspections of school-based early years provision reveals a picture of quality services delivered by highly qualified staff, skilled in helping to prepare children for their transition to primary school.

Since 2014, school-based early years provision has been given a separate rating by Ofsted as part of school inspections under the common inspection framework. This judgment feeds into the overall rating of the school's effectiveness.

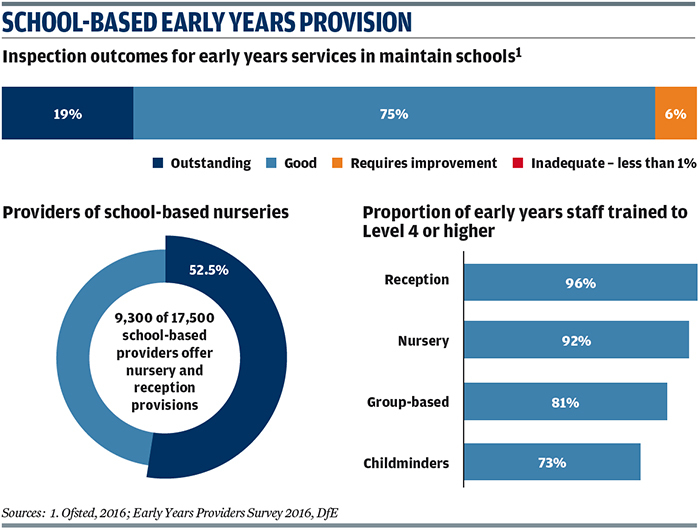

Not all schools with early years have a separate early years rating yet. However, Ofsted estimates about 94 per cent of school-based early years provision is either "good" or "outstanding". This compares with 95 per cent of private and voluntary nurseries or pre-schools.

Ofsted estimates 19 per cent to be outstanding and 75 per cent good. Meanwhile about six per cent "requires improvement" and less than one per cent are "inadequate".

Of 661 schools with early years provision inspected from September to December 2016, 10 per cent were outstanding for early years, 67 per cent were good, 18 per cent requires improvement and five per cent inadequate.

When it comes to quality of early years provision, much emphasis has been placed on the importance of staff qualifications.

Maintained nursery schools and nursery classes in primary schools differ from other types of provision in that they are required to have a qualified teacher present at all times.

The Department for Education's 2016 survey of early years and childcare providers confirms school-based provision tends to employ higher-qualified staff with 92 per cent of head teachers or early years co-ordinators at school nurseries qualified to at least Level 6 compared with 33 per cent of senior managers at group-based childcare.

There is evidence more highly qualified staff leads to better outcomes, with children in the most deprived areas benefitting most.

A 2016 Save the Children report on nursery provision in England suggests a child who attends a nursery without a highly qualified member of staff is four per cent less likely to reach a good level of development than one who attends settings with highly qualified workers.

Yet a study published earlier this year - conducted by researchers at the London School of Economics, University of Surrey and University College London and funded by the Nuffield Foundation - concluded staff qualifications at nursery do not determine how well children do at school.

This found children who attend a setting employing a graduate or graduates do better but the effects are "extremely small" - an increase in children's Early Years Foundation Stage scores of one third of a point where the total number of points available is 117.

One advantage of school-based nursery provision is that it can make the transition to school easier. The best early years providers are "very focused on preparing children for transition to school", says Ofsted.

Ofsted's 2014 good practice report on school readiness found a "mutual understanding of what was expected" between early years provision and school was key.

The government is keen to see more childcare offered on school premises. While private and voluntary settings may struggle - or be less keen to set up - in deprived areas, schools already serve these communities.

However, the quality of school-based provision in deprived areas has varied. In 2012, just 59 per cent of school-based early years provision in the most deprived areas was rated good or outstanding, compared with 83 per cent in the least deprived areas.

Encouragingly, this gap has decreased significantly in the past four years. In 2016, 86 per cent of school-based provision in the most deprived areas was rated good or outstanding compared with 95 per cent in the least deprived areas.

In Ofsted's early years report on disadvantaged children, published in July last year, the then chief inspector of schools Sir Michael Wilshaw said he firmly believed schools were best placed to lead on work to prevent disadvantaged children falling behind as primary schools were already successfully reducing the disparity between poorer children and their peers between the ages of five and seven. "They also have more access to specialist support to ensure smooth transition into reception from nursery," he wrote.

In total, 43 early years providers - all in high areas of deprivation - were visited by inspectors for this report, including 16 maintained schools with early years provision.

It found school head teachers "often demonstrated a strong moral purpose as leaders of their local community". In contrast, inspectors found the majority of pre-schools and childminders visited "worked on a purely business model of operation - giving places to those who requested the most hours".

While there is a push for schools to offer more childcare, funding cuts may mean they are less open to taking on extra responsibilities.

A survey conducted by the National Association of Headteachers (NAHT) in 2015 - in light of plans to extend free childcare entitlement from 15 to 30 hours per week - found the majority of providers of nursery education in schools reported they did not receive enough funding to cover costs, most commonly subsiding places from the rest of the school budget.

The NAHT warned without adequate funding schools may move away from providing nursery education. However, last month a new national early years funding formula came into force with 80 per cent of authorities seeing an increase.

Qualified staff deliver results at Wellfield

- Wellfield Infant and Nursery School, Cheshire

- Outstanding

- February 2016

Highly-qualified staff are a key factor in the success of Wellfield Infant and Nursery School in Cheshire.

The setting, which achieves good results for the most disadvantaged pupils and takes an active part in sharing good practice, has an experienced early years practitioner, leader and educator as head teacher.

Cathy Graham joined the school in 2011 and believes her expertise has shaped a school-wide appreciation of the importance of the early years and understanding of child development.

She is supported by Early Years Foundation Stage lead Kate Douglas, nursery teacher Karen Harrison and teaching assistant Diane Elsmere.

The school, which is maintained by Trafford Council, is rated "outstanding" overall by Ofsted and outstanding for its early years provision, where children "make excellent progress".

"The gap between the outcomes for disadvantaged children and other children is narrowing because teachers check on children's progress regularly and provide extra support," says the report.

Scrutiny and understanding of child development data and knowing how to use it to inform planning is vital, says Graham, who says that the setting takes a reflective, flexible approach and is always looking at what does and does not work.

"From one cohort to another, we are constantly reviewing timetables and group organisation - re-arranging groups according to shared next steps for children," she says.

The school has had particular success with boys - who are more likely to fall behind than girls at this stage.

Overall, 83 per cent of the pupils achieved a good level of development in 2015/16.

Disadvantaged pupils were very slightly ahead, with 83.3 per cent of those eligible for free school meals achieving a good level of development compared to 82.5 per cent of pupils not eligible for free school meals.

The school runs workshops for parents on topics such as learning through play and phonics.

These are available to everybody, but the members of the nursery team do approach certain families they feel would benefit most.

"We meet with them individually - when and where we need to - to give them some extra support and advice," adds Graham.

The school is involved in local teaching school alliances and supports teacher training and provides school-to-school support.

"We're able to share our expertise and see the benefit for the wider community," says Graham. "The other side is that our staff have really grown professionally from having these opportunities."

Graham, who was an early years adviser for Trafford school improvement service and now sits on the early years reference group, believes there is a benefit to having more highly qualified staff.

"I'm not saying schools are better than PVIs (private, voluntary and independent providers) - I have met people in all settings that are amazing early years practitioners," says Graham. "But I do think there is benefit to having people with higher level qualifications and training in child development as well as education as those two fit so crucially together for this age group."