Early Learning and School Readiness: Policy context

Derren Hayes

Tuesday, July 25, 2017

Since 2008, the Early Years Foundation Stage (EYFS) has underpinned early child development. The framework explains how good early education for children aged up to five supports child development in preparation for formal education.

The EYFS specifies:

- The areas of learning and development that must shape activities and experiences for children in all early years settings

- The early learning goals that providers must help children work towards (the knowledge, skills and understanding they should have at the end of the academic year in which they turn five)

- Assessment arrangements for measuring progress (and requirements for reporting to parents and/or carers).

The framework identifies three "prime" areas of development: communication and language; physical development; and personal, social and emotional development. In addition, there are four "specific" areas of learning: literacy; mathematics; understanding the world; and expressive arts and design.

Early education programmes must involve activities and experiences for children that fulfil the seven areas of learning and development, and how these can be shaped around the individual needs of children. Particular emphasis needs to be given to using play, creative thinking and active learning in planning and delivering activities.

The document makes clear that children develop and learn in different ways and at different rates, but outlines the "early learning goals" that should be aimed for.

Characteristics of good development

Summer-born children can sometimes be developmentally behind older peers. In addition, research shows that on average girls are more academically and emotionally developed than boys when entering reception, while children from poorer backgrounds can struggle.

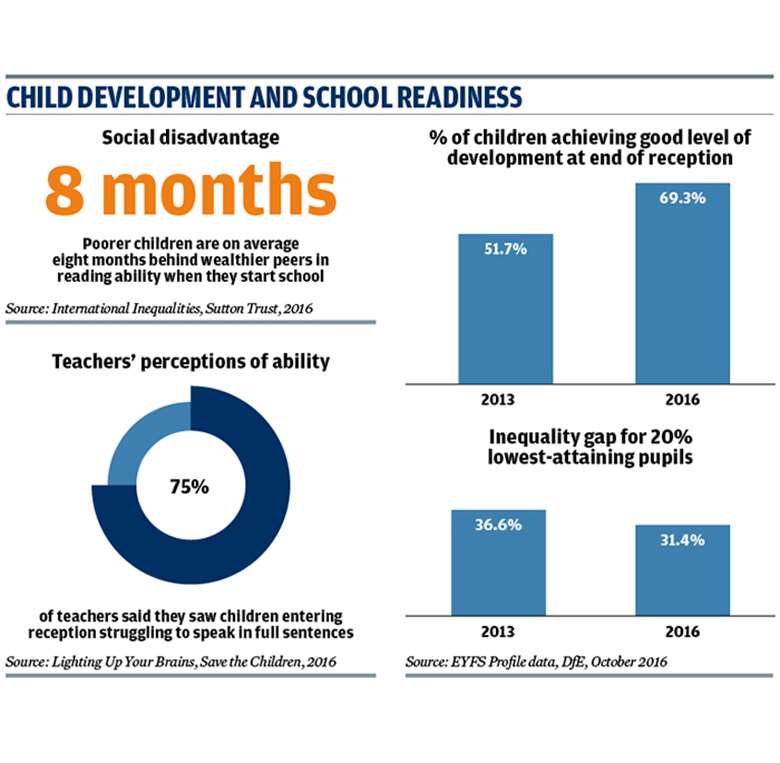

Research by the Sutton Trust shows children from economically disadvantaged homes are on average eight months behind in reading ability than their better off peers at age four. Some studies suggest there is an even wider gap between children from the most affluent and disadvantaged backgrounds.

However, he most recent EYFS profile data shows that in 2016 the percentage of all children achieving "a good level of development" was 69.3 per cent, a rise of three percentage points from 2015 and up from 51.7 per cent in 2013. Over the same period, the gap between the highest and lowest performers has closed, as has the variation in performance between different local authority areas. The EYFS "scores" for the lowest 20 per cent of children have improved from an average of 21.6 in 2013 to 23.3 in 2016, while over the same period the median score has remained the same at 34. This has seen the percentage inequality gap fall from 36.6 to 31.4 over the four-year period (see graphics).

The data also shows the gender gap has narrowed from 16.3 percentage points in 2014 to 14.7 in 2016.

The EYFS early learning goals set out the range of key personal characteristics and academic abilities that children with good development demonstrate.

Naomi Eisenstadt, former director of the national Sure Start unit, says quality of interaction between child and practitioner is key to ensuring children from low-income families are well prepared for school. However, she questions whether it is reasonable to place such responsibility on practitioners whose pay and training is often low. (see expert view, p30).

Assessing school readiness

The EYFS profile provides the best indicator of a child's progress in their first year of primary school. While there are likely to be strong correlations between a child's level of development when they enter school and their achievement at the end of reception year, the government is keen to develop a formal assessment of their abilities when starting education.

After scrapping a previous attempt to introduce a "baseline assessment" following opposition from early years groups, the Department for Education launched a fresh consultation in March on a new primary assessment in reception. The government hopes the measure will better prepare children for school. However, in their response to the consultation, teaching unions criticised the proposals as risking stigmatising children and damaging their self-confidence (see expert view, p31).

Early years leaders also fear that such an assessment would undermine the EYFS, and say introducing a formalised assessment of a child's academic abilities could incentivise childcare settings and schools to narrow their definition of what constitutes "school ready" (see Beatrice Merrick expert view).

An evidence review by University of Cambridge academics David Whitebread and Sue Bingham for TACTYC, the Association for Professional Development in the Early Years, highlights how there is no single agreed definition of school ready. Despite this, school readiness is increasingly being used by politicians to underpin policy decisions.

"The arguments surfacing about whether, how and why a child should be ‘made ready' are symptomatic of the far deeper tension growing within the early years education sector, in relation to a deep conceptual divide," they write in School Readiness: A Critical Review of Perspectives and Evidence.

"The disagreement about terminology and definition encapsulates a fundamental difference in conception of the purpose of early years education."

A framework developed by Unesco highlights that there has been a trend towards definitions that prioritise literacy and numeracy over more pedagogical approaches. It advocates a broader definition that incorporates not just a child's readiness for learning but that of their families.

A comprehensive review of childhood research carried out by TACTYC and the British Educational Research Association found that the prevailing notion of school readiness is for children to conform to "formal academic expectations", and conclude that "narrowly defined assessments" of school readiness disadvantage groups such as children with disabilities, summer-born children and those who are bilingual (see research evidence).

Improving transition practice

Despite the disagreement about what constitutes good school readiness among early educators, there is evidence to suggest some children are starting school without some of the basic skills needed to learn. A 2016 survey by Save the Children found that 75 per cent of teachers reported children entering reception class struggling to speak in full sentences.

Such evidence has encouraged policymakers and the early years sector to focus on improving support for children to help them transition to school more effectively. This is reinforced by an Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development study that shows a poor transition can undo the benefits gained from good early education (see research evidence, p31).

To ensure children experience a smooth transition between childcare setting and reception, a range of approaches have been developed by early years providers and schools, often in partnership, many with the strategic support of local authorities and multi-academy trusts. Innovations include appointing keyworkers to support children as they approach school starting age (see practice example, p36); running "speed dating" events where early years practitioners can meet teaching staff to find out about how they can prepare children for school (p35); and developing at-a-glance one-page fact files for all children that detail their abilities and learning goals (p38).

The renewed emphasis in the DfE on boosting social mobility through investing in the early years should help build on the achievements of recent years in narrowing the gap in EYFS profile scores between low-income and better off children. However, the debate over the role of early education in preparing children for school is likely to intensify if the government pushes ahead with its plans for a baseline assessment.

EXPERT VIEW: QUALITY INTERACTIONS ARE THE KEY TO NARROW ATTAINMENT GAP

Naomi Eisenstadt, senior research fellow, University of Oxford

The general election result probably means that early years policy is not going to be a high priority for a struggling minority government. Nonetheless, we can tell from the manifesto promises what is likely to be ahead. There was a clear interest among most parties in narrowing the gap in educational outcomes between poorer children and their better off peers. High-quality early years provision was linked to this vision of progress.

There is significant research that staff quality and particularly qualifications improves childcare standards. The relationship between quality in early years provision and improved child outcomes has recently been contested. My own view is that there is still enough evidence to believe that quality - particularly quality of interaction between young children and the staff who look after them - does result in improved school readiness for children from low-income families. The quality of that interaction is largely determined by the training and child development knowledge of the care giver. A strong understanding of language development helps the carer to engage the child with open-ended questions, supportive comments that encourage more complex dialogue, and enables more inventive storytelling. Language is key to both cognitive and social development.

I recently had an interaction that gave me cause for deep pessimism. The girl washing my hair told me that she had left school at 16 to take an apprenticeship in childcare, but gave it up for hairdressing. I asked why. Alarmingly she said that as a new apprentice she was "key worker" for nine children, including two-year-olds. She was expected to take as many as four children out on her own. She worked five days a week, full-time, for £3.05 an hour. She had no days in college, and had a few weeks of pre-service training. She didn't have C-grade English and maths GCSE. She left childcare for hairdressing because she felt too much pressure and too much responsibility. What a sensible young woman to recognise that it was too much responsibility for a 16-year-old with virtually no training, and what sounded like very little supervision.

So what does it tell us about early years policy? For me, it says that the government is very interested in ensuring childcare is "affordable". Workforce participation is contingent on making work pay and if parents have to pay too much for childcare, work will not increase family income. Increasing family income is an excellent aim, and poverty is bad for children, but the expansion of free hours, the relaxation of entry barriers into childcare, and the continued effort to get more childcare for very limited investment will not result in the quality experience needed to narrow the gap in school readiness.

To get the staff needed to provide the essential quality for language development we need higher entry barriers, better training, and more graduates in early years. We will only attract better candidates if wages go up. I am not hopeful. Building really high-quality early education and care can make a difference but it comes at a price, a price the government seems unwilling to pay.

EXPERT VIEW: BASELINE ASSESSMENT IS FLAWED

Neil Leitch, chief executive, Pre-school Learning Alliance

There is a many-headed character in Greek mythology called the Hydra, and it was said that if you cut off one of its heads, two would grow back. We have a lot of Hydra policies in early years at the moment - those stubborn policies that simply refuse to go away.

Take baseline assessment, for example. This isn't a new policy. It was already introduced 20 years ago before being scrapped and replaced by the then-named Foundation Stage Profile in 2002. So why does government continue to persist with something so obviously flawed?

Picture the scenario: you're four years old and you've been at nursery, pre-school, or with your childminder for a few weeks when a practitioner takes you aside, sits you down, puts a tablet in front of you on which questions such as "Can you point to the green hexagon?" appear. Imagine that the results of this assessment are then used to measure your progress as you advance through school.

It doesn't take an expert to see that assessing a child in this way will only ever serve to provide a limited - and most likely, inaccurate - snapshot of their attainment. The education select committee published a report warning the government about the potentially negative impact of testing young children in this way.

Thankfully, this isn't how early assessments currently work. The cross-sector Better Without Baseline campaign led by early years organisations, teaching unions and education experts - including the Alliance - was successful in getting the government to drop its baseline testing pilot scheme in April 2016.

However, just as the Hydra's head grows back, the government is once again proposing to introduce a new baseline assessment in reception from September 2019.

It is important to measure children's development and chart their progress, but this is already done very successfully through the Early Years Foundation Stage Profile.

Indeed, the early years is as much about developing children's broader skills - such as emotional control, physical development, creativity, and critical thinking - as it is about laying foundations for the development of numeracy and literacy skills.

So why then is the government so keen to reintroduce such a maligned measure?

To put it bluntly, baseline assessment provides an easy way for government to theoretically hold schools to account.

A recent government consultation - the responses to which are currently being analysed - proposed relieving the current testing burden on children in Key Stage 1 by simply shifting it onto their younger peers.

The Alliance, along with many others in the sector, responded to this consultation warning that as well as being harmful, unreliable and disruptive, baseline testing is always likely to be statistically invalid due to the variety of tests available.

It is simply not right to put unnecessary pressure on children at the beginning of their formal educational journey. At this important stage of a child's life, we should be focussing on fostering a love of learning and supporting their development, not using them as a way to rank and measure schools.

EXPERT VIEW: WE NEED A MORE FLEXIBLE DEFINITION OF SCHOOL READINESS

Beatrice Merrick is chief executive, Early Education

There are times when we talk about the education system as though each stage was just preparation for the next - early years as a preparation for primary, primary as preparation for secondary, with the ultimate aim of churning out work-ready widgets. In reaction to this, there is a growing parent movement including groups such as Let our Kids Be Kids and More Than a Score that seeks to reclaim the importance of childhood as a distinct phase of life that should be cherished and enjoyed in its own right.

The focus on school readiness comes from well-intentioned concerns about certain groups of children achieving less well than their peers throughout the school system, and the observation that the gaps begin to open early on. Plenty of research and data confirm the existence of a gap, but we have to be wary of policies that also seem to be driven by unscientific attempts to define what a child "should" be able to do at a certain age. The "good level of development" measure, for example, is not a measure based on typical development, as can be seen by the difference between maths and literacy scores and other areas of learning in the Early Years Foundation Stage (EYFS) profile. The goals for maths and literacy have been artificially raised in the mistaken belief that "hot housing" these skills early on will boost later performance. In fact, the opposite is true, and children who have missed out on time playing and being active to be drilled in letters and numbers are losing opportunities to develop skills such as self-regulation and oral language which are a more lasting and effective basis for later learning.

We must not forget that children's development is not uniform nor linear, and that some children will be ready to sit still, learn to read or regulate their emotions sooner than others. This is well illustrated by the vexed question of deferrals for summer-born children, who - on average - do less well than their spring- or autumn-born peers throughout the school system. Deferring entry to reception may be a fix for some individual children, but international evidence tells us the only systemic cure is to extend the phase of early childhood education upwards, to around age seven. Countries with a formal school starting age of seven do not experience the phenomenon of summer-born disadvantage, as the differences that are stark at age four or five have begun to level out by then.

That should ring alarm bells with us about whether the problem is really about children not being ready for school, or rather about schools not being ready for children. Every child is born ready to learn - it's hardwired into us, and researchers such as Alison Gopnik have demonstrated that the peak of our creativity and flexibility as learners is around age four (as we develop we trade in some of that creativity for the "efficiency" of tried and tested thought patterns - we learn less because we know more). Children need a curriculum and pedagogy which is suited to their stage of development and some children entering year 1 (and beyond) will still benefit from a continuation of the EYFS before they are ready for the national curriculum. Growing numbers of exclusions of five-year-olds are another worrying sign that year 1 classrooms are not always ready for the needs of all children.

Of course, there is plenty of evidence that high-quality early education can help to reduce the degree of difference, though it is vital that schools work with parents - not only in the early years - to make sure every parent and carer understands and has the best opportunity of providing the best home learning environment. The conditions will then be in place for school readiness: with child, parent and school all having a key part to play in ensuring each is ready for the other.

FURTHER READING

The EYFS Statutory Framework, March 2017

Reception Baseline Assessment, Dr. Guy Roberts-Holmes and Dr. Alice Bradbury, University College London, Institute of Education TACTYC, 2017

School Readiness: A Conceptual Framework, Pia Rebello Britto, Ph.D, UNESCO, April 2012

Literature Review On School Readiness, David Whitebread & Sue Bingham, University of Cambridge, TACTYC, 2011