Alone in a new land

Louise Hunt

Tuesday, October 31, 2017

Unaccompanied asylum-seeking children represent a rising part of England's looked-after children population. Louise Hunt asks how they are cared for and how councils can best meet their needs.

Since 2015, when Europe's ongoing refugee crisis took hold, the number of unaccompanied asylum-seeking children (UASCs) looked after by local authorities has more than doubled and is still rising. The complexity of their needs, many of whom have experienced trauma, is creating multiple challenges for looked-after children's services.

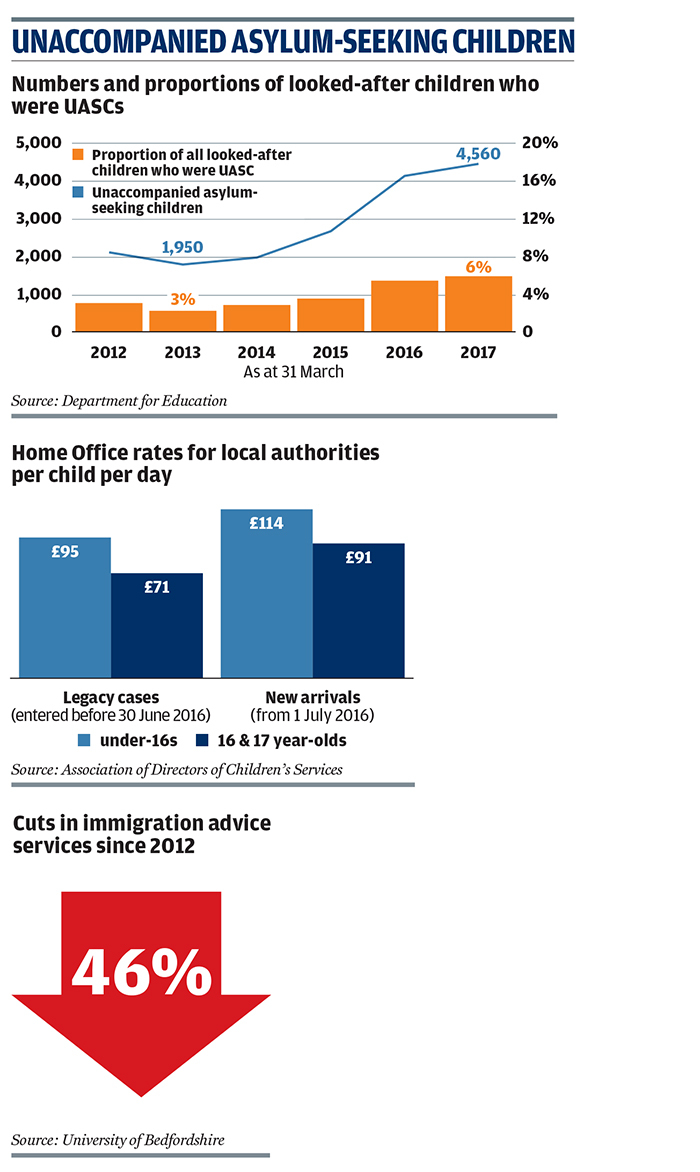

As of 31 March 2017, there were 4,560 UASCs in care, up six per cent on last year, according to Department for Education statistics published in September.

The DfE notes that the rise in UASCs in care over the past two years has influenced an overall increase in the number of looked-after children in England, with more children starting to be in care in 2017 than ceasing, compared to 2016 when there was a one per cent shift the other way.

There is significant variation in the numbers of unaccompanied children across the country. Historically, UASCs have been concentrated in areas where they first make entry into the country, especially Kent, Croydon and Hillingdon. These local authorities have come under enormous strain, but there is now a new system for sharing corporate parenting responsibility more equitably across England.

Philip Segurola, until recently Kent County Council director of specialist children's services, recounts how over the summer of 2015, the number of UASCs entering the UK at Dover reached unprecedented levels. "Young people were coming over in large groups. Over three months we received more than 1,000 arrivals."

In July 2016, the National Transfer Scheme (NTS) was implemented to alleviate pressure on these authorities. The transfer protocol allows a local authority with more than 0.07 per cent of UASCs in its total child population (just over one in 1,400) to request a new arrival is transferred to a participating local authority that is below that threshold.

"We had been advocating for a more equitable spread for a long time," says Segurola. "The National Transfer Scheme was an essential resolution, we couldn't cope with that level of demand."

Because it is still above the threshold, Kent is transferring all new arrivals. "So far, we have transferred just over 300 children and young people," says Sarah Hammond, assistant director for West Kent. "We are careful to explain they will go into a temporary placement and they will be going onto another part of the country," Hammond says.

If a permanent placement cannot be found in the region, Kent contacts the NTS hub. This serves as a clearing system that allocates new arrivals to one of the 12 regional strategic migration partnerships. Each partnership area has a rota of local authorities that agree to take children. On average, UASCs are staying two to three weeks in Kent before moving to their placement.

The Home Office would not provide data on transfers nationwide, but the DfE statistics on looked-after children indicate that the number of UASCs in the "gateway" authorities has reduced compared to 2016. "We understand this is a result of the implementation of a National Transfer Scheme resulting in some of these children being distributed across other local authorities within the country," states its report.

However, not all local authorities are participating. Last October, CYP Now reported that based on the differing numbers of councils within each region, a minimum of 38 councils might not be involved while three of nine local authority regions had opted out citing funding pressures. The Home Office did not respond to CYP Now's request for the latest information on how many or which authorities had opted out.

The gap between government funding and the true costs for looking after UASCs continues to be a major issue. Although the Home Office grant per child per day was increased slightly when the NTS was implemented - from £95 to £114 for under-16s, and from £71 to £91 for 16 and 17 year-olds - the Association of Directors of Children's Services estimates this barely covers more than half of the actual costs to local authorities.

"COUNCILS STRUGGLING"

Dave Hill, Association of Directors of Children's Services immediate past president, who was in post during the NTS roll-out, says: "Some authorities argued they had agreed to take young asylum seekers through other Home Office schemes and were struggling with saturation. But it did cause a fair amount of bad feeling among participating authorities."

The dispersal scheme came under pressure last autumn when the government agreed to relocate separated children who were affected by the dismantling of the Calais "Jungle" camp. Around 300 children were assessed by British social workers and brought back under the Dubs Agreement, introduced in the Immigration Act in May 2016. It was expected that up to 3,000 eligible "Dubs" children would be brought over, but in February this year then immigration minister Robert Goodwill (now the children's minister) halted the scheme at 350 after some authorities said they could not manage more UASCs in their care.

"At the time, the National Transfer Scheme was mid-way into being implemented," says Hill. "It wasn't designed to have large numbers coming in one go. That put huge pressure on finding appropriate placements. I was fearing the system would collapse at that point - participating local authorities went beyond the call of duty as did fostering services."

Indeed, fostering services have also had to adapt to the rapidly changing requirements. Although the majority of UASCs are older boys aged 16 to 17 likely to be placed in semi-independent residential accommodation, under-16s and girls will be looked after by foster carers.

The introduction of the transfer scheme and the expectation of many more "Dubs" children led to a big recruitment drive for foster carers with UASC expertise, explains Jackie Sanders, director of communications and public affairs for the Fostering Network.

"These foster carers need experience in recognising the trauma and loss these children are likely to have experienced; they need to be able to help with practical things such as language, bridging cultural divides and helping young people understand what it's like to live in the UK, as well as help them navigate the logistics of the asylum system," she says.

A Fostering Network survey of fostering services undertaken found 40 per cent of providers were looking to recruit carers for unaccompanied children. Some recruitment campaigns have been very successful, says Sanders. "Some services are now moving those carers into mainstream care because there hasn't been the demand they thought."

Overall, the implementation of the transfer scheme has helped hone looked-after children's services' abilities to respond to the complex needs of unaccompanied children, believes Hill. "I think the national distribution scheme brought most authorities to the point where they knew they had to have a clear strategy in place. Before, I would say just under half of local authorities had a strategy."

During the Calais camp clearance period, Hill says social care, health and education partners worked together to tap into emergency government funds for supporting the physical and mental health needs of these young people. "There are children with post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms that have debilitating consequences if not dealt with," he says. "Getting services into place was quite complicated. Schools were being used as hubs for referring on to CAMHS when required."

However, he adds that the delay in publication of the DfE's strategy for safeguarding unaccompanied asylum-seeking children, which had been scheduled for May, is a disappointment. The strategy is expected to advise on the broader safeguarding issues that should be covered in assessment, such as trauma. The DfE told CYP Now the strategy would be published "in due course".

Voluntary organisations are also concerned that more separated young people could be vulnerable to safeguarding issues since the introduction of the National Transfer Scheme.

"The focus of the scheme has been on relieving pressures on local authorities, but decisions on transfer are not always around the best interests of the child," says Ilona Pinter, policy and research manager at the Children's Society, a member of the Refugee Children's Consortium.

LENGTHY DELAYS

The chief concern is that many referrals are taking place when the child has already been in the entry authority for over a month. "There isn't currently any time limit on transfer and there is a lack of consistency over how long transfer is taking," says Pinter. In some cases the child has been transferred after six months, having settled with a foster carer and started school. The consortium advises social workers they are not obliged by law to continue with a transfer if it is no longer in the child's best interest.

It is also concerned that more young people eligible for care, are falling through gaps because of a shortage of specialist immigration legal advisers, especially if transferred to areas that are "advice deserts".

Research for The Children's Society uncovered a 46 per cent reduction in immigration advice services between 2012 and 2016. Delays in receiving advice can mean older UASCs, particularly those aged over 17, may miss out on being properly cared and planned for, according to a consortium briefing paper on the NTS published in August. "We work with young people who find they have less support or are cut off from social care support entirely. We are seeing young people who have experienced destitution, are undertaking sex work or other exploitative work," Pinter adds.

TURNING 18

These issues are expected to get worse. In principle, unaccompanied young people are entitled to the same leaving care support as British looked-after children, but forthcoming changes to immigration law will limit the amount of funded support councils will be able to provide for those who lose the legal right to remain.

Even for those who are eligible to stay, providing long-term support presents a big budgetary challenge. Kent County Council, for example, is bracing itself for when the majority of its 2015 cohort of arrivals turn 18. "We are climbing steadily to a 1,000 UASC care leavers who are not eligible for transfer," says Sarah Hammond.

Segurola adds: "That legacy will run through to five years, so although the immediate crisis has passed in relation to the numbers of looked-after children, we've got this longer-term legacy with the care leavers and that poses a different set of challenges, particularly around longer-term accommodation options. On the basis of what the Home Office has currently offered us, the funding shortfall is in excess of £3m."

There may have to be another resolution.

FURTHER READING

An Update to Cut off From Justice: The impact of excluding separated and migrant children from legal aid, The Children's Society, August 2017

Briefing on the National Transfer Scheme, Refugee Children's Consortium, August 2017

Unaccompanied Asylum Seeking and Refugee Children (special thematic report), Association of Directors of Children's Services, November 2016

This article is part of CYP Now's Children in Care supplement. Click here for more

Read the full supplement online, or download as a PDF