Youth Work in the UK (England)

Priya Patel, policy, research and public affairs assistant, The Children’s Society

Monday, August 26, 2019

Focuses on the development of UK youth work.

- Edited by Jon Ord with Marc Carletti, Susan Cooper, Christophe Dansac, Daniele Morciano, Lasse Siurala and Marti Taru

- Extract From: The Impact of Youth Work in Europe: A Study of Five European Countries (September 2018)

This book is the culmination of a European project funded by Erasmus and is a small-scale study of youth work. It does not attempt to draw a representative sample of the diversity of youth work practice across Europe. All the projects involved also accord with the broad parameters of youth work as defined by the Council of Europe (2018), which defines youth work as "a relational, critical and youth-centric practice".

The chapter focuses on the development of UK youth work.

A version of youth work emerged in the early 19th century within forms of "popular" education whereby working-class groups sought to provide education for themselves rather than allow their upper-class "betters" to do it for and especially to them. These were seen as revolutionary and even political, the upper-class soon began imposing their own versions of "provided" education for themselves, rendering the "popular" education, which education was provided by the upper-class, largely invisible.

The authors suggest that youth work can also be traced back to Sunday schools for the children of "the lower orders", set up by Christian philanthropists in the late 18th century.

Charities overwhelmingly provided youth work up until 1939. A legal obligation for local authorities to provide youth work was achieved through sections 41 and 53 of the 1944 Education Act. Despite this, the pattern of provision remained largely unchanged post-war, and the dominance of voluntary organisations continued for some time.

New Labour reforms

In 1997, New Labour, led by Tony Blair, oversaw a renewed focus on the needs of young people and issues of poverty. Despite youth work coming into the spotlight, the series of developments created by the New Labour government failed to understand how youth workers nurture young people's development or assist them in understanding their potential. Their final policy document "Aiming High for Young People" produced a large capital investment in the construction of youth centres, under the title "Myplace". However, the initiative failed to fully recognise the educational role of youth work in such spaces.

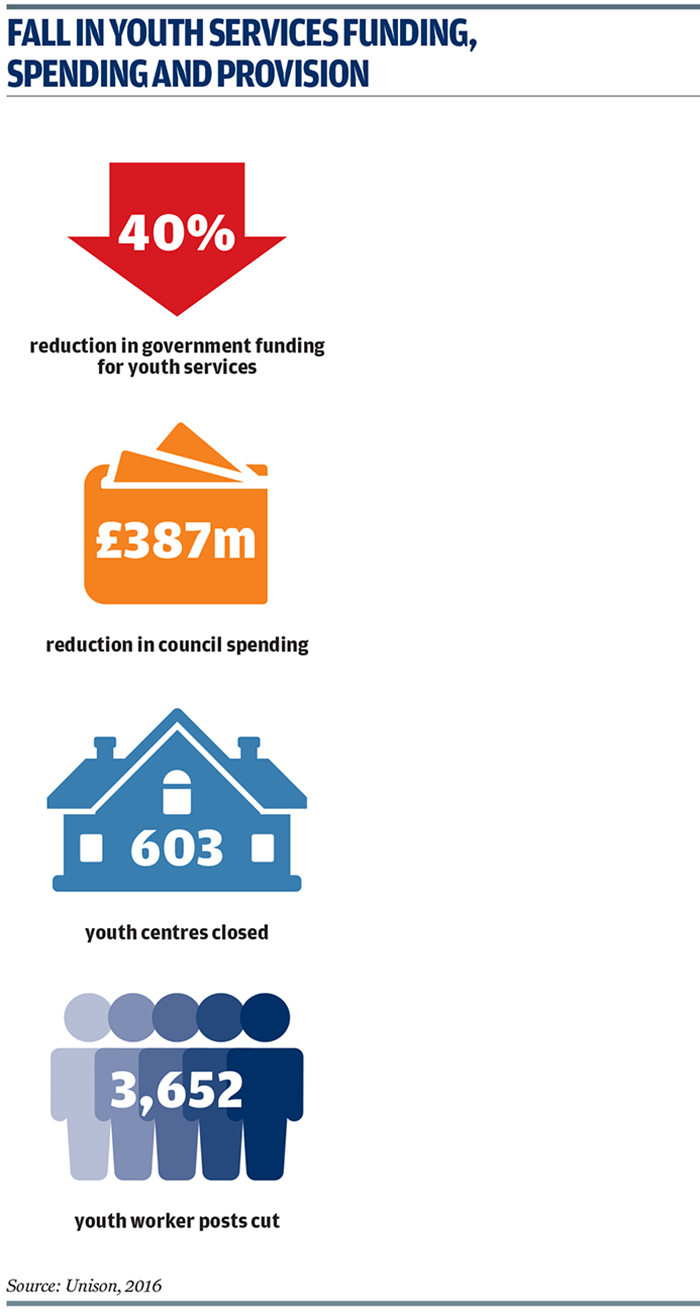

The subsequent coalition government cut overall financial support to local authorities by 40 per cent. Due to the statutory responsibility to provide services, some local authorities admit to having to "outsource" their responsibilities.

In 2013, a new policy, Priorities for Youth, outlined a new set of goals for youth work within education. Key priorities included:

- Raising standards for all and closing the performance gap between the highest and lowest achieving young people

- Providing access to enjoyable, non-formal learning opportunities that help them to develop enhanced social cognitive skills and overcome barriers to learning

- Creating inclusive, participative settings in which the voice and influence of young people are championed, supported and are evident in the design, delivery and evaluation programmes.

National Citizen Service

The National Citizen Service became the flagship youth policy of the coalition government. Its budget in 2015 was £140m and would have kept open most of the year-round, locally-based youth service facilities which by then had been closed.

Across the four nations, multiple policy developments over recent decades include the Welsh amendment to the Learning and Skills Act 2000 and The National Youth Service strategy in Wales. In Northern Ireland in 1997, the Department for Education's "Youth Work: A Model for Effective Practice" responded to the lack of reflection on the diverse needs of young people of different ages. Recent cuts to the UK youth service budget have impacted the charity sector severely.

Implications for practice

- The article illustrates that, in recent years, as a result of New Labour's developments, youth workers in the UK increasingly find themselves co-ordinating their work with other professionals working with young people - making effective approaches to joint working particularly important.

- In recent years, the creation of youth-work-specific targets has made youth work more accountable to specific, tangible and measurable results. A 2011 select committee report highlighted how difficult it was to measure the impact of services.

- The article concludes by acknowledging that budget cuts in recent years have made it a continuing struggle to defend and sustain youth work - and highlights the particular need in this context to provide credible evidence of impact.

FURTHER READING

The Right Start: How to Access Families From Birth and Support Early Intervention, The Children's Society (2014)

Multisystemic Therapy as an Intervention for Young People on the Edge of Care, Simone Fox, Zoë Ashmore (2014)

A Marriage Made in Hell: Early Intervention Meets Child Protection, Brid Featherstone, Kate Morris, Sue White (2013)

Sure Start: The Development of an Early Intervention Programme for Young Children in The United Kingdom, Norman Glass (2006)

Influences of Family-Systems Intervention Practices on Parent-Child Interactions and Child Development, Carol M. Trivette, Carl J. Dunst, Deborah W. Hamby (2010)

Defined by History: Youth Work, Bernard Davies (2010)

The Impetus for Family-Centred Early Childhood Intervention, Barry Carpenter (2007)

- The Children's Society is a national charity that works with the country's most vulnerable children and young people. Research summaries provided by Priya Patel