Post-traumatic Stress Disorder in Young Children Three Years Post-trauma

Charlotte Goddard

Tuesday, January 3, 2017

Children who experience traumatic events such as car accidents, assaults and natural disasters are at risk of developing Post-traumatic Stress Disorder, with symptoms including disturbing memories and nightmares, and feeling like the world is unsafe.

Authors Richard Meiser-Stedman, Patrick Smith, William Yule, Edward Glucksman, Tim Dalgleish

Published by The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, November 2016

SUMMARY

Researchers from the University of East Anglia wanted to find out how prevalent PTSD is in children three years after a trauma, and how well parents recognise their child has been affected. They also examined whether early signs of stress shortly after a trauma could predict PTSD later on, and whether factors such as the severity of the trauma, a child's intelligence and the mental health of their parents can predict the intensity of future PTSD.

Researchers followed 114 children between the ages of two and 10 who had attended an emergency department in South London between May 2004 and November 2005 following a motor vehicle accident. Assessments were made two to four weeks after the trauma, six months after and three years after with 71 of the 114 taking part in all three assessments. For younger children, reports of PTSD symptoms came from parents. In other cases, reports were taken from both parents and children.

The researchers found children who show signs of stress soon after a trauma will not necessarily go on to suffer PTSD after three years. A significant minority of children develop PTSD that persists for years but many bounce back naturally. They also found there was a discrepancy between parent-reported symptoms of PTSD and child-reported symptoms, suggesting parents are not recognising symptoms in their children.

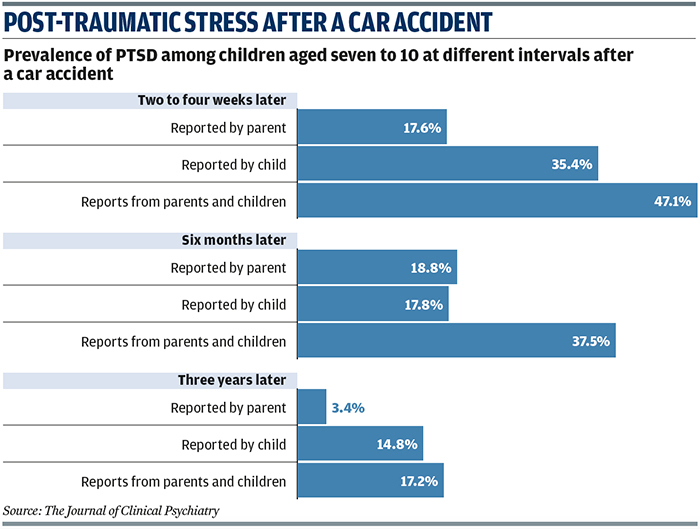

Based on parental reports, 11.5 per cent of children had PTSD symptoms directly following the incident. Six months later this had risen to 13.9 per cent, and three years later it was down to 2.8 per cent. According to parents, the figures for seven- to 10-year-olds were 17.6 per cent, 18.8 per cent and 3.4 per cent.

However, based on the accounts of those aged seven to 10, 35.4 per cent were assessed as suffering PTSD immediately after the incident, falling to 17.8 per cent six months later and 14.8 per cent after three years. When reports from children and parents were combined the proportions suffering PTSD at the three assessment points were 47.1 per cent, 37.5 per cent and 17.2 per cent respectively.

The severity of the initial trauma was associated with the development of PTSD six months after the accident but had no links to whether a child had PTSD three years later. The age of a child did not appear to be linked to whether or not they developed PTSD and intelligence was not a factor.

Children were more likely to suffer PTSD if their parents had also developed it. However, most parents of children still experiencing difficulties after three years did not recognise their child's PTSD, even if they had suffered PTSD themselves.

IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTICE

Young children may develop clinically significant PTSD that persists for years and in many cases is not recognised by their parents. The findings suggest relying on parental reports may not be adequate for diagnosing PTSD in children. The study also strengthens the case for considering parental mental health in the aftermath of trauma as a way of predicting the impact on children. Parents should be given support around their own post-traumatic stress as well as the PTSD experienced by their child.

FURTHER READING

- The Post-traumatic Stress Disorder Diagnosis In Pre-school- and Elementary School-age Children Exposed to Motor Vehicle Accidents, Richard Meiser-Stedman and others, The American Journal of Psychiatry, October 2008. A paper from the same research team using the same sample of children.

- Rates of Post-traumatic Stress Disorder in Trauma-exposed Children and Adolescents: Meta-Analysis, Eva Alisic and others, The British Journal of Psychiatry, May 2014. A report into the incidence of PTSD among children and young people.

- Outcomes of Traumatic Exposure, Frederick Stoddard, Child & Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics, April 2014. A report into the range of adverse outcomes arising from childhood trauma.