Intrafamilial Abuse: Policy context

Derren Hayes

Tuesday, October 31, 2017

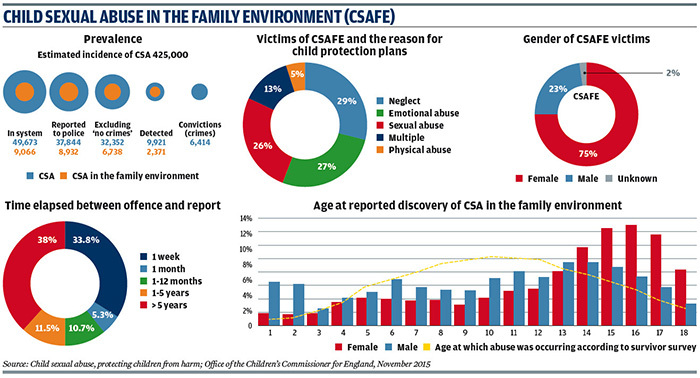

Detailed analysis of police files by the Office of the Children's Commissioner for England shows that around one in four reported child sexual abuse cases were classed as child sexualabuse in the family environment (CSAFE).

The latest Department for Education characteristics of children in need 2015/16 data shows 50.6 per cent of children referred to social services had a primary need of abuse and neglect, while 17.4 per cent were classed as living in "family dysfunction" and 8.7 per cent a "family in acute stress". Upon completion of a child in need assessment, the five main safeguarding factors identified were: domestic violence (49.6 per cent of cases), mental health (36.6 per cent), drug misuse (19.3 per cent), emotional abuse (19.3 per cent) and alcohol abuse (18.4 per cent).

A study of councils' safeguarding activity by the Association of Directors of Children's Services (ADCS) supports the DfE research findings. The Safeguarding Pressures 5 report, published in December 2016, shows the proportion of referrals to children's services for abuse and neglect have risen from 29 per cent in 2007/08 to 53.5 per cent in 2015/16. The ADCS data also shows domestic violence and parental mental health as the two main factors identified. In addition, the two main reasons for issuing child protection plans are neglect (45 per cent) and emotional abuse (35 per cent).

Over an eight-year period, the rate per 10,000 of plans issued due to emotional abuse - which incorporates factors linked to domestic abuse - has risen by 149 per cent. This is one of the reasons why Safeguarding Pressures 5 highlights concerns over the "toxic trio" of parental mental health, substance misuse and domestic violence. It cites research undertaken in an Eastern region authority that found 90 per cent of cases were linked to the toxic trio.

Identifying intrafamilial abuse can be difficult. Analysis by the Office of the Children's Commissioner for England found that 38 per cent of intrafamilial child sexual abuse cases are not reported for at least five years (see graphics). In addition to children being unable or reluctant to disclose abuse - illustrated by the "Q Family" case in Sheffield (see practice example, p38) - parents and carers can engage with agencies and appear to comply when in fact abuse is taking place.

Policymakers have developed legislation and guidance to help services identify and safeguard children at risk, and the launch in 2012 of the Troubled Families programme, with £440m attached, created a dedicated national initiative to tackle parental problems, some of which are the causes of abuse.

Child sexual abuse

Intrafamilial sexual abuse is sometimes referred to as incest. For the purposes of safeguarding children and young people, a family member who involves a child or young person in (or exposes them to) sexual behaviour is committing intrafamilial child sexual abuse, even where relationships are deemed to be consensual.

The children's commissioner report - Child Sexual Abuse, Protecting Children From Harm - highlights the challenges faced by practitioners of identifying child sexual abuse in a family environment (CSAFE). Analysis of case files found that just a quarter of intrafamialial sexual abuse victims were on a child protection plan due to sexual abuse, perhaps indicating other risk factors had been identified earlier. Only a third of CSAFE victims reported abuse within a week of it happening. In addition, reporting of abuse peaks in the mid-teens, despite most abuse taking place between ages nine and 12.

The report shows that a male family friend or father are the main perpetrators of CSAFE, and that three quarters of victims are girls.

Another potential barrier to establishing prevalence is the fact that there is no statutory definition for intrafamilial child sexual abuse.

The children's commissioner report uses a definition of abuse that takes place in or outside the home by a family member or someone linked to the family context or environment, whether or not the perpetrator is a family member.

An evidence review by Research in Practice, NSPCC and Action for Children used a slightly narrower definition of: "sexual abuse of a child by an adult in a familial setting". It cites figures from a 2011 study by Radford et al that shows one per cent of 18- to 24-year-olds reported sexual abuse perpetrated by a parent or guardian. The study concludes that experiencing neglect is "very likely" to increase a child's vulnerability to intrafamilial abuse.

Key legislation includes:

- Working together to safeguard children, 2015: inter-agency guidance to safeguard and promote the welfare of children

- Sex Offenders Act 1997 and Sexual Offences Act 2003: created and amended notification arrangements for sex offenders

- Criminal Justice Act 2003: sets out arrangements for assessing risks posed by sexual or violent offenders

Domestic abuse

The Crime Survey for England and Wales, published in July 2017, estimates that two million people aged 16 to 59 were victims of domestic abuse in the past year, most being women. A little over one million domestic abuse-related incidents were recorded by the police in the year ending March 2017. Following investigations, 464,886 offences were domestic-abuse related in the year ending March 2017 - a 10 per cent increase on the 421,185 offences recorded the previous year.

Domestic abuse is the main factor for children being referred to social services, being a child in need, placed on the child protection register and taken into care. Research by Radford et al (2011) estimated that 20 per cent of children have been exposed to domestic abuse. The link between domestic abuse and child maltreatment is highlighted by the Pathways to Harm, Pathways to Protectionstudy by Sidebottom (2016), which found that domestic abuse was a factor in more than half of serious case reviews between 2011 and 2014.

Radford's study also found that a third of children who witnessed domestic abuse experienced another form of abuse. In addition to being a child protection risk, the presence of domestic abuse can also have detrimental effects on emotional wellbeing.

Children's charity Barnardo's says even if children are not physically harmed, "children may suffer lasting emotional and psychological damage as a result of witnessing violence". It has developed a family assessment and support service with Newport City Council to ensure children affected by domestic violence receive speedy help (see practice example, p36).

Despite rising levels of domestic violence, and greater awareness of the impact it can have on children, a recent report by Ofsted and the Care Quality Commission flagged up concerns that agencies are not doing enough to prevent domestic abuse (see expert view). Drawn from findings of joint targeted area inspections (JTAI), it highlighted that the sheer scale of domestic abuse means it can be all too easy for police, health professionals and social workers to focus on short-term responses to incidents.

It concluded there is still a lack of clarity about "how to navigate the complexities of information sharing", and there needs to be greater consistency in the definition of harm, and in the understanding of whose rights to prioritise.

The government has pledged to introduce a new Domestic Violence and Abuse Bill that will see the establishment of a domestic violence and abuse commissioner to stand up for victims and survivors, raise public awareness, monitor the response of statutory agencies and local authorities, and hold the justice system to account in tackling domestic abuse.

Key legislation includes:

- Serious Crime Act 2015: created a new offence of "controlling or coercive behaviour in an intimate or family relationship".

- Domestic Violence, Crime and Victims Act 2004: created the new offence of "causing or allowing the death of a child or vulnerable adult". A 2012 amendment introduced an offence of "causing or allowing serious physical harm to a child or vulnerable adult".

- Adoption and Children Act 2002: amended the definition of harm in the Children Act 1989 to include "impairment suffered from seeing or hearing the ill-treatment of another".

Parental problems

Studies have found that the potential for parenting capacity to be undermined and children's health and development to be harmed by parental substance misuse is considerable, particularly when other risk factors such as domestic abuse and mental health difficulties are present.

The groundbreaking 2003 Hidden Harm report estimated that there were up to 350,000 children of problem drug users in the UK. In addition, it estimated that 1.3 million children were living with a parent who misused alcohol.

Having a parent who misuses substances significantly increases a child's chances of being harmed, either deliberately or accidently.

In addition, substance misuse and parental mental health problems are closely linked. Department of Health data shows that:

Increased rates of substance misuse are found in individuals with mental health problems affecting up to half of people with severe mental health problems;

Alcohol misuse is the most common form of substance misuse by people with mental health problems, followed by cannabis

The Royal College of Psychiatrists states that 68 per cent of women and 57 per cent of men with a mental health problem are parents. It points out that many children and young people will live with a parent with mental health conditions and associated substance misuse problems. But some keep their condition a secret, making it harder for them to get the help they need.

As well as increasing the risk of child abuse or maltreatment, such problems can also result in children taking on caring roles for their parent. It can affect every aspect of a child's life and leave them vulnerable to developing mental illness themselves, says the college.

"Some children withdraw into themselves, become anxious and find it hard to concentrate on their school work. They may find it difficult to talk about their parent's illness or their problems especially when they have had no explanation of their illness. This may stop them from getting help," college guidance states.

"Children can have physical health problems and struggle with school and their education, especially when they live with parents in poverty, poor housing or have an unstable life."

In one study by the Institute of Public Care at Oxford Brookes University, the "toxic trio" of domestic abuse, substance misuse and mental ill health was present in 29 per cent of child in need and child protection plans. It found that just one in five children living in these families had positive outcomes.

Many of these families have been worked with through the government's Troubled Families Programme. In its first phase, the initiative targeted workless families and those involved in crime, many of whom the then Prime Minister David Cameron said were "the source of a large proportion of the problems in society, drug addiction, alcohol abuse, crime".

Councils identified 120,000 troubled families in England to work with over three years. The government claimed that 99 per cent of families were turned around in that time. However, critics questioned whether the measures of success were too simplistic. Nonetheless, the scheme was extended to a further 400,000 families in 2015, and is a significant source of funding for authorities working with troubled families, the definition of which has been extended to include parents or children affected by a mental or physical health problem.

Key legislation includes:

- Mental Health Act 1983 can be used to remove a mentally ill adult who poses a risk to a child

- Children Act 1989 outlines circumstances in which child protection action is necessary

- Children Act 2004 includes measures to prioritise treatment for substance misusing parents

Commissioner's View Disclosure is crucial

By Anne Longfield, Children's Commissioner for England

The high-profile cases of child sexual exploitation and the ongoing independent inquiry into child sexual abuse (CSA) continue to make headlines. Yet the fact remains - most children who do suffer from sexual abuse are abused within the family.

At the end of 2015, I published research showing that as many as 1.3 million children in England have been sexually abused by the time they reach 18. It is hard to measure the exact scale of CSA in the family because of data collection deficiencies, but the evidence suggests that familial CSA accounts for two-thirds of all child sexual abuse.

While a system that waits for children to tell someone will never be completely effective, disclosure is key. Our survey of adult survivors revealed that two-thirds of victims did not tell anyone what was happening. Many don't see themselves as victims - groomed into believing otherwise. Many fear reprisals. Some think or fear they will not be believed or are terrified about the consequences for their family, others scared about speaking to the police or going to court (see research evidence, p38).

We need to create conditions in which children feel secure enough to tell an adult. Relationships are key - children are more likely to disclose if it is someone they trust. Without disclosure, identification of victims is difficult - the signs and symptoms of abuse can be ambiguous. Where professionals know children well enough to spot when something has changed, in the context of a trusting relationship, they are better placed to identify the signs of abuse. Better training for teachers on how to spot abuse is essential.

Our research also showed that a significant number of cases of sexual abuse in and around the family involve young people as the perpetrator. Many are also victims themselves. Much more needs to be done to make sure personal, social, health and economic education lessons include teaching about harmful sexual behaviour. I've also been working with the NSPCC and others to develop the "Is It Okay?" service, which is designed to help young people at risk of abuse, and provide advice and counselling.

We should also be ambitious about the help we provide for victims. I have championed Iceland's Barnahus model. Since it was introduced there, twice as many cases of sexual abuse are being investigated each year and the number of prosecutions has tripled. It delivers better criminal justice and therapeutic outcomes by providing a home-like setting to provide the child with familiarity, with all the services located at the house. That way, the child only has to visit one location rather than multiple stressful visits to intimidating buildings. I want to see Barnahus rolled out here.

Child sexual abuse linked to the family casts a long shadow over the life of victims and survivors. A strategy for the prevention of CSA requires co-ordination of all sources of support for children and families to ensure that victims are identified and helped. Some progress is being made, but the scale of the challenge remains huge.

Ofsted View Stop abuse happening in the first place

By Eleanor Schooling, national director for social care, Ofsted

Prevent, protect and repair - those are the key messages from our recent report about domestic abuse. Ofsted, the Care Quality Commission (CQC), HM Inspectorate of Constabulary, and HM Inspectorate of Probation took a deep dive to see how social workers, police and health professionals are dealing with the ever-present problem of domestic abuse.

Our report, published in September, found that domestic abuse is an endemic problem that is affecting the lives of one in six children. We found that dedicated professionals are often doing a good job to protect victims. But too little is being done to prevent this crime in the first place, and to repair the damage it causes.

Inspectors saw that work with families was often in reaction to individual crises. This work was often done well. But it's clear that keeping children safe over time needs an eye on the longer term. This focus on the immediate crisis leads agencies to consider only those in imminent risk. Agencies are not always looking at the right things and, in particular, not focusing enough on the perpetrator.

Inspectors often found that professionals were not clear about how and when to share important information to protect children.

Both Ofsted and CQC have identified in previous reports that this was a serious failing in the safeguarding of children and young people by adult mental health services and substance misuse services. This matters because we know that the effects of witnessing domestic abuse can last a life time.

I want to see leaders and managers focus more on preventing domestic abuse from happening in the first place. Domestic abuse must be viewed as a public health issue - with a widespread public service message to shift behaviour on a wide scale. We need to teach children about what healthy relationships are like.

Finally, we're calling for leaders and frontline professionals to concentrate more on changing the behaviour of perpetrators. If we do so, our reward will be to make a dent in the seemingly overwhelming numbers. Police in England recorded 421,000 domestic abuse crimes last year, while the number of domestic abuse victims is 6.5 million.

So that's why we are calling on leaders, managers and frontline professionals to prevent domestic abuse from happening in the first place, protect the victims and repair the damage caused by this damaging behaviour.

FURTHER READING

Domestic Violence Disclosure Scheme, Home Office, July 2012

National Evaluation of the Troubled Families Programme 2012-15, DCLG, October 2016

Controlling or coercive behaviour in an intimate or family relationship, Home Office statutory guidance, 2015

Guidelines on domestic violence, NICE, 2014

Joint Protocols For Developing Partnerships Between Drug And Alcohol Workers And Children's Services Public Health England, 2013

Think Family: Improving The Life Chances Of Families At Risk Cabinet Office, 2008

This article is part of CYP Now's special report on intrafamilial abuse. Click here for more