The policy context for residential care

Derren Hayes

Tuesday, June 7, 2016

The status and make-up of residential children's care, quality of provision, and issues for commissioners and providers.

According to the most recent Ofsted data, 6,031 children were living in residential child care as of 31 March 2015. This figure represented a fall of 0.1 per cent from the previous year and accounted for just 8.7 per cent of the 69,310 looked-after children placements on that date.

Despite being relatively small in number, residential care is increasingly being used for older children with complex needs and a history of multiple placement breakdowns. The support needs of this group of young people tend on the whole to be higher than those in other forms of care and pose a significant challenge to residential care providers, whether in the statutory or independent sector.

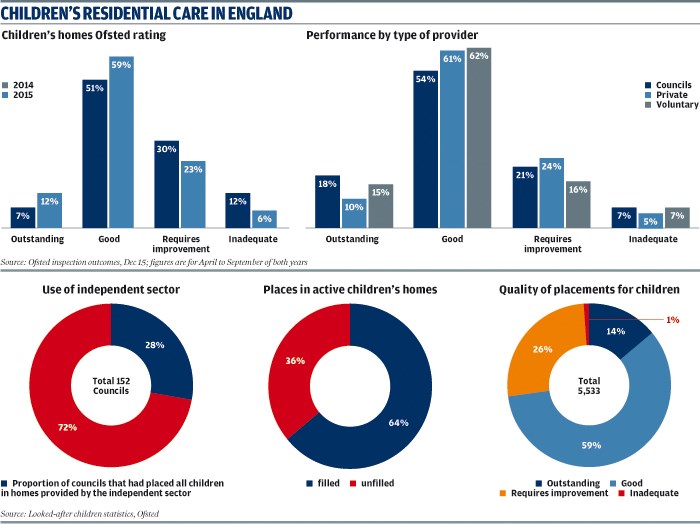

The factors behind these trends are multiple, complex and longstanding. High-profile abuse cases and concerns about the quality of provision has seen commissioners move away from using residential care to the point where it is now regarded often as an option for children whose needs are too great for foster carers to cope, and where adoption is not a realistic option. In addition, the high cost of providing intensive therapeutic support for those in residential care make it an economically unsustainable model for use with anything but the most troubled children. In fact, the fall in the number of children now placed by councils in residential care has seen 41 of England's 152 local authorities (28 per cent) no longer have their own provision and only commission places from the independent sector (see graphics).

Download these graphics as a PDF

Analysis earlier this year by the National Centre for Excellence in Residential Child Care (NCERCC) and the Independent Children's Homes Association (ICHA) found young people in children's homes are six times more likely to have mental health problems than other looked-after children, three-quarters have issues with violence, nearly half have suffered abuse or neglect, more than a third are assessed as having special educational needs and 29 per cent have had five or more previous placements.

Another key issue has been the lack of a consistent and clear strategy from government on the role that residential child care plays in the care system. In recent years, the government has spent tens of millions of pounds on extending the right for fostered children to stay in placements up to the age of 21 and increasing post-adoption support services, and has also signalled its intention to boost the rights of care leavers. By contrast, there has been no such flagship funding or policy initiatives to indicate that residential child care is a priority. In fact, the recent injection of investment through the Children's Social Care Innovation programme focused on helping councils find ways to reduce the need for residential care.

But there is hope that the policy void could be about to change. Last autumn, the Prime Minister appointed the then government adoption adviser Sir Martin Narey to lead a review of children's residential care. The review, due to be published this summer, has the challenging remit of examining how to deliver quality provision and improved outcomes while achieving value for money.

Narey has already indicated that he is unlikely to recommend extending the Staying Put rights enjoyed by fostered children to those in residential care due to the high cost involved.

Whatever recommendations the Narey review makes, sector experts hope it will prompt the government to devise a clear vision for residential care, one that focuses on the positive contribution that it can make for children in care.

The NCERCC and ICHA analysis says there is a need for government to uphold residential child care as "a positive choice for some children" and be seen as part of the "wider care system rather than in isolation".

The Narey review is also looking at secure children's homes provision and how it can be improved. Earlier this year, Hampshire County Council agreed to take on the co-ordination of placements across the 14 secure homes in the country. The Association of Directors of Children's Services hopes the review will help devise solutions to the major shortage of provision that currently sees children have to wait for places (see ADCS box, p20).

There seems little doubt that the Narey review will be instrumental in shaping the future of children's residential care, yet at a time of such policy uncertainty, the overall standard of residential care is on the rise.

Quality of provision

Ofsted data on inspections of children's homes shows the proportion of settings rated "outstanding" for overall effectiveness rose from seven to 12 per cent while those rated "good" rose from 51 to 59 per cent in the first six months of 2015/16 compared with the same period the year before. Meanwhile, there was a corresponding fall in the proportion of homes rated "requires improvement" and "inadequate" (see graphics). The uplift has been achieved across the range of different types of provider, although the voluntary sector has the highest proportion of homes rated good or outstanding (77 per cent, compared with 72 and 71 per cent for council-run and private homes respectively). While some local authorities no longer run their own homes, 18 per cent of council-run homes were judged outstanding by Ofsted in 2015, compared with 10 per cent of those in the private sector. However, there are fewer private homes rated inadequate (five per cent) than in other sectors. Overall, 73 per cent of children were living in residential care homes rated good or outstanding.

The improvement in provider inspection outcomes has been attributed largely to the introduction of new quality standards for residential care in April 2015. Under the quality standards, homes have to show inspectors how they are supporting children to achieve positive outcomes and place a greater emphasis on settings liaising with schools and colleges on meeting a child's education targets and ensuring homework is done.

Valerie Tulloch, improvement and consultancy manager at the Children's Homes Quality Standards Partnership (CHQSP), a research initiative between Action for Children and the Who Cares? Trust, says the quality standards have helped homes focus on meeting the specific needs of children.

"It's about staff using professional judgment rather than meeting the requirements of Ofsted regulations," she explains. "This means staff demonstrating that they are basing their approach on evidence-based practice. It has led to staff feeling more confident."

However, Tulloch warns the sector against complacency. She maintains that standards in residential care have come from a "low starting point" and that inspection judgments generally reflect a stabilising in education outcomes rather than an improvement.

"It is a good start but I think there will be more rigour in future," she says. "Perhaps more detail needs to be placed on how homes function. There are more challenges ahead for providers."

There is evidence emerging that Ofsted could be taking a tougher approach in inspections of children's homes. A report published by National Children's Bureau in April highlighted concerns over "inconsistent" and "unfair" interpretation of the quality standards that were leading to "black and white judgments based on narrowly defined outcomes". NCB recommended Ofsted improve its local engagement with homes through workshops, webinars and sharing good practice case studies (see Enver Solomon, below).

In an effort to clarify some of these concerns, last month Ofsted published a "myth buster" guide to help residential care providers understand what inspectors are looking for.

The CHQSP also published the evaluation on its work to help providers implement the quality standards earlier this year.

Transition to independence

Efforts to increase adoption and special guardianship orders, as well as extend foster care placements up to 21, have increased permanency for many looked-after children. However, most children in residential care still leave at 18. Efforts have been made to improve the support they receive for making the transition to independence, with some residential child care providers developing dedicated "Moving On" teams to equip young people with practical life skills (see Break practice example, p28).

The government has signalled its intention to extend care leaver support to all young people up to 25, but NCB says more evidence is needed on the long-term outcomes for children who go through residential care. It is specifically calling for Staying Put rights to be extended to those in care homes.

NCB also wants a greater focus on how homes address children's mental health problems. It backs a recommendation from the education select committee for all children to receive an initial mental health assessment upon entering care. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines on childhood attachment highlight the difficulties looked-after children have in making attachments and the vital role that professionals working in residential settings can play in helping a child form strong relationships and improve their resilience.

Looked-after children are at greater risk of ending up not in education, employment or training, while some studies have shown that up to a third of young adults in prison have been in care. Both private and statutory residential child care providers are working to improve how they prepare young people for further education, training and work, with some even offering apprenticeships to the young people they care for (see practice examples, p28).

In addition, youth justice and care campaigners have raised concerns that children's home staff are too quick to call police for minor incidents that occur in care settings. This is leading to children in care homes being unnecessarily criminalised, they argue. DfE data shows that 19 per cent of children aged 13 to 15 living in care homes have been criminalised.

Issues for providers

The vast majority of residential care places are in the private sector. However, as a result of local authorities placing fewer children into residential care, occupancy rates are falling - Ofsted figures show that around a third of all available places were unfilled on 31 March 2015.

Another trend in provision is the stagnation in fees paid by local authorities for placements. DfE research in 2011 found the average weekly cost of a children's home placement was £2,689 compared with £676 for foster care. A recent ICHA survey found 67 per cent of providers reported fees had stayed the same over the past year, with a further 11 per cent reporting a fall. With children's services budgets under pressure, councils are looking at ways to reduce costs, but providers' bodies say 42 per cent of providers are reporting a worsening financial picture.

Despite this deteriorating picture, Ofsted data shows the number of providers rose slightly in 2015. However, a rise in the last three years in the number of children placed in residential care outside of a local authority's area suggests commissioners were struggling to find the right care placements (see research evidence graphic, p23). Higher expectations of the quality of service that providers deliver are also mirrored by greater expectations on the standards of staff. Alongside 2015's quality standards, new residential child care qualifications were introduced. The new Level 3 Diploma for Residential Childcare updates the skills needed for working with children and young people in residential settings, including an understanding of child and young person development (see RESuLT practice example, p27).

From this year, all residential care staff employed before April 2014 must have obtained the new qualification which, while welcomed by providers, is causing concerns that it could cause a recruitment crisis - those employed afterwards must complete within two years.

Tulloch says Ofsted will be closely monitoring residential care providers to ensure staff have the new qualifications. She adds that it could cause problems for homes that specialise in short breaks as they tend to use casual staff.

"It's about the number of hours people work," she explains. "If someone is only doing eight hours a week and has to find the time to do assessments and written work then they may not have the time to do sufficient shifts.

"In five years' time maybe everyone will be qualified, but in the meantime do we have to tell staff to leave?"

Residential care given the status it deserves

By Enver Solomon, director of evidence and impact, National Children's Bureau

The announcement of the Narey review was largely welcomed by the sector: Martin Narey is well respected and has had significant influence with government on recent children's policy relating to adoption and social work reform.

The review should clearly state that residential care must not only be considered when all other placements have failed. A child with complex multiple needs can benefit greatly from being in a residential home environment, in a setting that suits their preferences and where they are supported by a team of staff together with access to additional specialist help if needed. A foster home is not always the best option for these children, but too often they arrive in residential care after multiple foster placements have broken down.

Equally important is that the review does not propose reform for reform's sake. It is only just over a year since new quality standards for children's homes were introduced, following close consultation with professionals and looked-after children and young people. The standards are generally perceived as being positive and beneficial, despite concerns about the new way of working they signalled. It would not make any sense to move away from them. However, the new Ofsted inspection framework that follows the implementation of the standards is seen by some providers as being an unnecessarily bureaucratic burden. The Narey review may address this by proposing variation in the inspection framework that would allow for high-performing homes to have less-frequent inspections, as is the case with schools.

The review will also hopefully seek solutions to other persistent problems. First, looked-after children still suffer poor physical and mental health outcomes and more work is needed to track longitudinally the outcomes of children who go through residential care. The government must give serious consideration to a recent education select committee recommendation that all looked-after children have an initial mental health assessment conducted by a qualified health professional.

Second, the perceived low status of working in a children's home needs to be addressed.

In the years ahead when the sector looks back at the legacy of the review, given it was commissioned from the very top of government, it's likely it will be viewed as having been instrumental in shaping the future of residential care for children. Hopefully, it will also be remembered as the moment that the residential sector's position was elevated to be given the status it deserves in transforming the lives of some of the most vulnerable in our society.

ADCS: More insight into secure children's homes

By Dave Hill, president, the Association of Directors of Children's Services (ADCS)

Secure children's homes provide the most vulnerable children with vital help and support in times of extreme crisis or distress.

While these kinds of placement can be seen as a "last resort", they can also be used to help children to regulate their own risk-taking behaviour as part of a long-term care plan. The skills needed to care for children who have experienced abuse, neglect, trauma and personal loss are highly specialised. Residential care workers in these settings tend to have had greater training and turnover is generally lower, which helps children to build trusting relationships with an adult, sometimes for the first time.

There are now only 14 secure children's homes in England so finding a placement can take time. The welfare system operates close to maximum capacity and at times there is no availability. This is a very worrying situation for directors of children's services which is why ADCS has been working with the Department for Education, the Secure Accommodation Network and others to bring about greater stability and build capacity in this market.

Individual local authorities rarely make secure placements, only one or two each year. This can make the co-ordination of, and learning from, this experience difficult for commissioners and the homes themselves. Hampshire County Council recently set up a dedicated unit to broker secure placement requests. This will allow us to gather data and share much-needed insight in terms of demand, children's needs and the causes of placement difficulties. This will be invaluable in improving services.

This feature is part of CYP Now's special report on residential care. Click here for more