Big increase in suicides among vulnerable children known to social services

Neil Puffett

Thursday, October 25, 2018

The number of suicides among children who are either in care or are known to social services as being at risk of abuse or neglect has increased by more than 30 per cent in the last year, it has emerged.

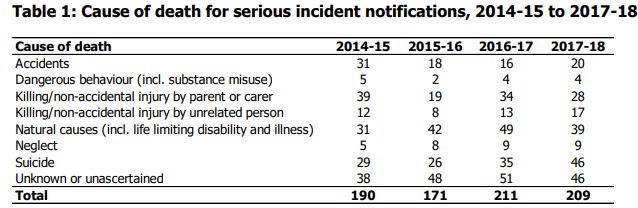

Figures published by Ofsted show that there was an increase in the number of suicides reported by local authorities from 35 in 2016/17 to 46 in 2017/18, a rise of 31.4 per cent. It represents the highest level of suicides among at-risk children in recent years - in 2015/16 there were 26, and in 2014/15 there were 29.

The true number of suicides could be even higher as councils are required to notify Ofsted within five days of a death occurring, when the precise cause may be unclear. There is no requirement for councils to update Ofsted once a cause of death has been established.

As a result, in 2017/18, a total of 46 deaths are classed as "unknown or unascertained", while it is possible that initial categorisations such as "accident", of which there were 20 in 2017/18, or "dangerous behaviour", of which there were four in 2017/18, could later be established to be a different cause of death.

The statistics show that, although there was an increase in suicides, the overall number of child deaths remained relatively constant with 209 cases in 2017/18, compared with 211 in the previous year.

The rising level of suicide comes amid growing concerns about ongoing funding cuts, and increasing demand on the child protection system.

The number of children in care, and numbers of those believed to be at risk, have been growing steadily in recent years. The number of children in care is rising at its fastest rate in five years, with 72,670 children in care at the end of March 2017, compared with 70,440 the year before and 69,480 in 2015.

However, councils have less money to support looked-after children and those deemed to be at risk of abuse or neglect. Analysis by the Labour Party, published in April, found that councils are spending the equivalent of nearly £1bn less in real terms on children's services than they were in 2012.

In January, the Local Government Association warned that children could be left in circumstances of risk unless the government acts to plug an estimated £2bn funding gap by 2020.

And earlier this week a group of 120 organisations warned that support that vulnerable children and young people rely on is "at breaking point", with the government "ignoring them" in its spending plans.

There are also concerns about the availability of mental health services for children and young people. A recent report by Education Policy Institute found that child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS) are struggling to cope with a rise in demand and are turning away as many as one in four young people referred for support.

Mental health assessments for looked-after children had been due to be piloted in 10 local authorities from May 2017 - but the project was delayed, and is now due to get under way in June 2019.

Natasha Finlayson, chief executive of the charity Become, said assessments of children and young people's mental health and wellbeing as they enter care are "inconsistent", and often fail to identify those who require specialist care and support.

"Initial assessments are rarely completed by qualified mental health professionals, so signs of significant mental health difficulties caused by pre-care trauma can be missed," she added.

"Far too many young people are turned away from CAMHS because they don't meet the threshold for treatment, which is generally unacceptably high - in many CAMHS services for example, suicidal young people are only offered an urgent appointment if they have already attempted suicide.

"Furthermore, budget cuts to CAMHS in over recent years mean that many specialist teams offered targeted support for looked-after children have been abolished."

The Ofsted report does not contain details of when or how incidents occurred. However, one case to feature in the statistics for 2016/17, when there were a total of 35 suicides, was the death of a teenage girl in February 2017, the first young person to take their life in a secure children's home for more than 20 years.

A DfE spokesman said: "The death of any child is a tragedy, and nothing is more important than keeping our children safe.

"As part of the Children and Social Work Act we now have in place a new independent child safeguarding review panel that will look at serious cases - such as suicides - to try and identify what can be done differently so that we can intervene earlier where vulnerable children are concerned."