Provider treats young people with mental health problems

Derren Hayes

Tuesday, January 29, 2019

West Midlands-based Cove Care provides step-down placements from mental health in-patient units.

- It prides itself on providing children's home staff with up-to-date training on mental health issues.

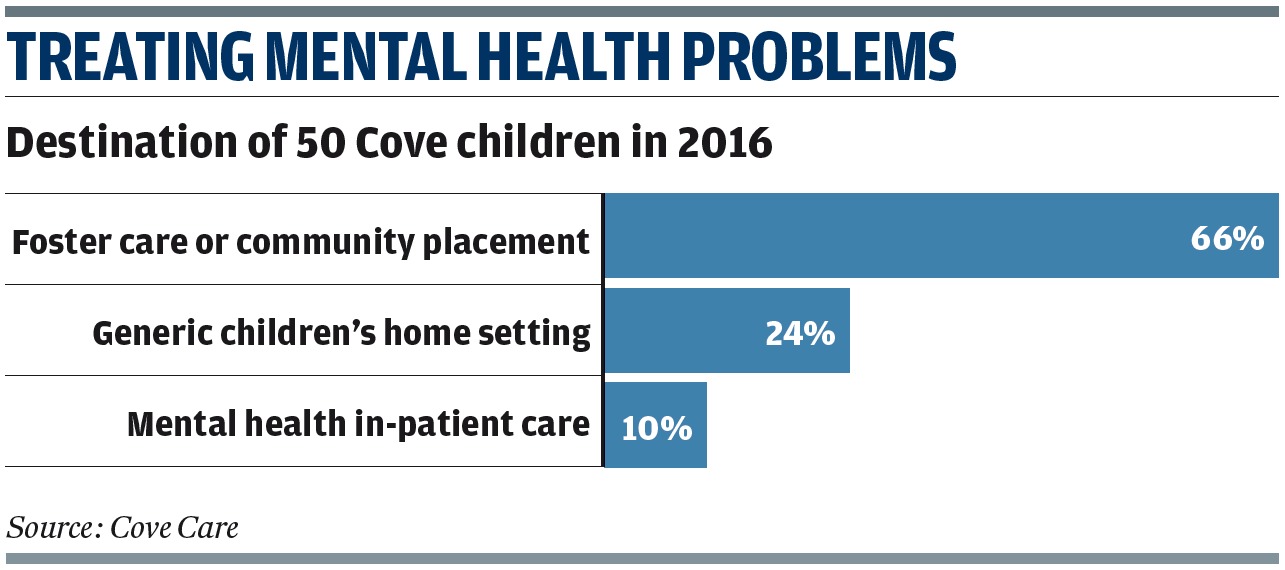

- Two-thirds of young people it cares for move on to care placements in the community.

ACTION

The government's recent introduction of mental health checks for all children entering residential care reflects increased recognition of the greater levels of trauma many looked-after children experience. This growing awareness has also led to children's homes providing better therapeutic support and improving the mental health skills of their workforce.

Cove Care is a residential care provider that has specialised in working with looked-after children with severe mental illness since 2008. Founded by registered mental health nurse Lee Smith and nurse and psychotherapist Bev Cyrus, Cove has developed an expertise in helping children that leave in-patient mental health units to return to care placements in the community.

"These young people have often been in in-patient units for more than a year," explains Smith. "We have good relationships with tier 4 child and adolescent mental health service (CAMHS) settings."

Cove also provides an alternative to in-patent units for young people whose problems are severe but hospital is not deemed an appropriate setting for them.

Many of the young people that Cove cares for have been diagnosed with post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or have complex post-trauma difficulties, so a thorough assessment of their emotional and trauma history is taken before arrival.

"The trauma is caused by living in troubled backgrounds over many years," says Smith.

"Troubled family environments tend to have the hallmarks of high risk such as exposure to criminal behaviour, substance misuse and mental health problems.

"These upbringings can be the cause of a child's mental health problems and can also compound existing mental illnesses such as early onset psychosis.

"Often this experience can result in significant personality dysfunction."

When young people arrive at one of Cove's four homes, all of which are in the West Midlands, it is crucial that they are able to feel safe and secure in their environment "as without that, you can't do much else like formal therapy", explains Smith.

Once a young person feels safe at the home, more focused therapy such as EMDR (eye movement desensitization and reprocessing) therapy can begin. This is an interactive psychotherapy technique used to relieve stress and has been shown to be effective in the treatment of PTSD.

In addition to undertaking therapy, residential care staff work hard to establish boundaries and routines with the young people, particularly around meal and bed times. Keyworkers monitor their progress and help them relearn patterns of behaviour.

Smith says it can take anything from "a few days to weeks" for young people to "come out of this crisis stage", but once they have they move into the "acute stage", which focuses on helping them build resilience to prevent crisis recurring.

"It's a very individual timescale," explains Smith. "Some respond quite quickly and are ready to leave after 12 months, while those with more complex problems can stay more than two years."

Through its sister company Amber Consultancy, Cove provides comprehensive mental health training for its staff - it has 14 beds across the four homes with staffing levels dependent on demand. Smith and two members of staff are qualified mental health first aid trainers, and workers also get advice from a psychologist and psychiatrist.

"We deliver an annual training day and if we have a young person coming in with particular needs we hold specific training sessions on how to meet those," Smith says. For example, staff have recently undergone training on how to respond to young people trying to harm themselves with ligatures.

"Most staff don't have that experience and were worried about how to respond to that sort of behaviour," he explains.

"It is not necessarily high risk in terms of suicide but there is a high risk of misadventure; hurting themselves by accident.

"This type of behaviour can be misinterpreted so it requires a specific degree of training for the staff. It's important to give an emotionally neutral response so that the worker does not reinforce the idea that this is a frightening thing - young people need staff that don't get too upset about their behaviour."

Smith is to be involved in writing a national pathways document for specialist mental health residential care providers, and believes it an area more providers will develop expertise in.

"We're doing a lot of work that tier 3 CAMHS do," he explains. "CAMHS are overstretched and the residential care sector can help young people to stablisise."

IMPACT

Cove aims to support young people to be able to return to their family, a foster care placement or standard children's home.

Research it carried out in 2016 found that of the 50 children it worked with that year, 33 left to go into a foster care or the community. Others went into more generic children's homes, while a further five young people went back into mental health in-patient care.

"Mental health problems are often unclear and we sometimes identify issues that need addressing in a tier 4 CAMHS setting," says Smith.

Click here to read more in CYP Now's Residential Care special report