Gangs and Criminal Exploitation: Policy context

Derren Hayes

Monday, July 29, 2019

Defining exploitation

The Children's Society's recent Counting Livesreport sets out the variety of forms child criminal exploitation (CCE) can take. It can include children being forced to work in cannabis factories, being coerced into moving drugs or money, made to shoplift or pickpocket, or to threaten other young people. It has recently become associated with one specific model known as "county lines". In this model, organised criminal networks exploit young people and vulnerable groups to distribute drugs and money across the country through dedicated mobile phone lines often from cities to counties - hence the term county lines.

In a report from the National Crime Agency, 88 per cent of English police forces reported county lines activity. The agency recently assessed that there are more than 1,500 lines operating nationally, with evidence of increasing levels of violence.

The Counting Lives report highlights that all too often children involved in this activity are criminalised instead of being seen as victims and offered support. A factor in this is the lack of a statutory definition of CCE. The Children's Society uses a definition from young people, who describe it as "when someone you trusted makes you commit crimes for their benefits".

Prevalence of gangs

The National Crime Survey includes data from the Office for National Statistics that shows 27,000 children in England identify as a gang member. However, a report published in February by the Children's Commissioner for England analysed data from a wide variety of sources including that held by youth offending teams, children's services and local safeguarding children boards to produce a more complete picture on the extent of young people's links to gangs.

The Keeping Kids Safe report found that 313,000 children aged 10 to 17 knew someone they would define as a street gang member. This included 33,000 children who were a sibling of a gang member and a similar number who know a gang member and have been a victim of violent crime in the previous 12 months. Just one in five gang members or associates are known to children's services and youth offending teams, the analysis found (see expert view, below).

Much of the data collected measures the extent of gang-related crime committed by young people. Levels are lower than a decade ago, but figures suggest it has been rising recently.

The London Assembly's gang crime and violence dashboard shows that the number of victims of serious youth violence rose around 50 per cent between 2014 and 2018, while the recorded knife crimes with injury of under-25s rose 60 per cent over the same period. Conversely, "gang flagged" offences over that time fell by a third in the capital.

Youth Justice Board data shows knife possession offences committed by children rose from 4.5 to 7.5 per 10,000 children between March 2014 and 2017. Cautions of 10- to 17-year-olds for knife or offensive weapon offences have risen from a low of five per 10,000 in 2014 to eight per 10,000 in March 2019. By comparison cautions/convictions of over-18s have remained largely stable over the decade.

Indicators of exploitation

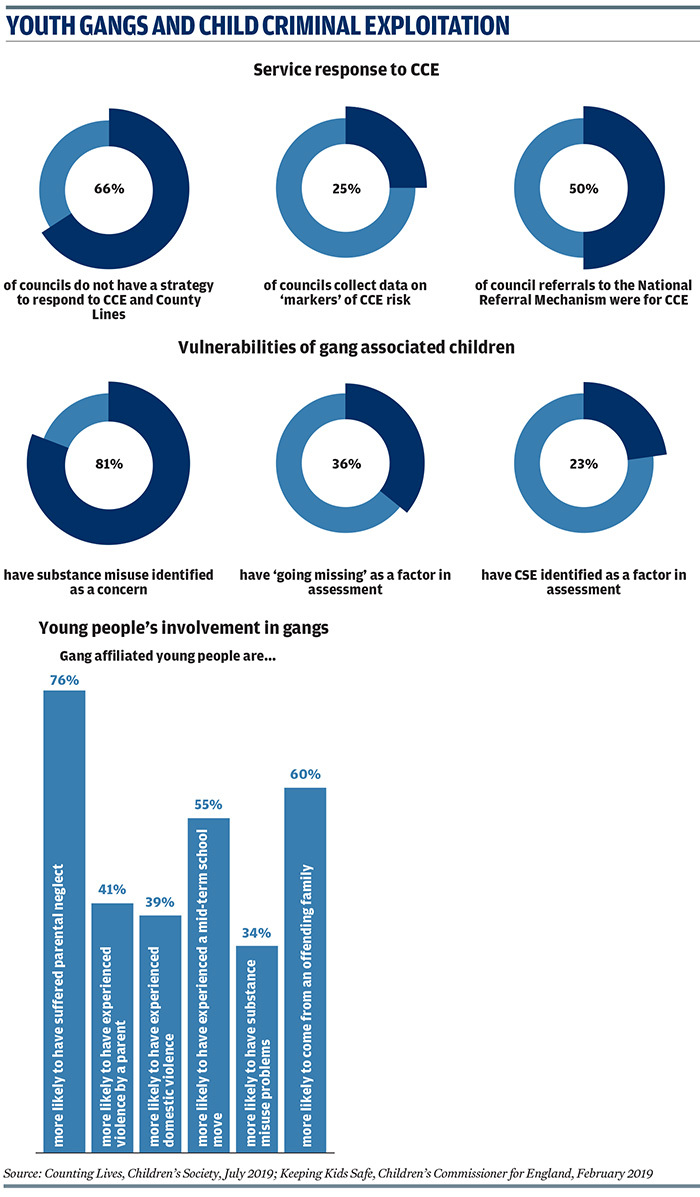

A report published late last year by Ofsted, the Care Quality Commission and justice inspectorates concluded that all children are vulnerable to exploitation, not just specific groups. However, there are a number of characteristics that can indicate a child is at risk of CCE or involved in gangs. Analysis by the children's commissioner found that gang-associated children tend to have a history of substance misuse (81 per cent), go missing from home or a care setting (36 per cent) and have sexual exploitation identified as a risk factor (23 per cent).

Its work also shows that gang-affiliated children are significantly more likely to have experienced a chaotic and traumatic home life such as violence by a parent and neglect than other young offenders (see graphics).

According to The Children's Society, data on arrests of children aged 10 to 17 for drug-related offences provides the best proxy data available on children exploited by criminal groups. Comparison of this shows that more children are arrested for "possession with intent to supply Class A drugs" than "possession" alone. Between 2015/16 to 2017/18, there was a 13 per cent rise in the number of 10- to 17-year-olds arrested for possession with intent to supply Class A drugs. This number rises to 49 per cent if data from London is excluded.

Over the same period, there was a 34 per cent rise in drugs-based stop and search instances where firearms or offensive weapons were found suggesting a link between drug-related crimes and youth violence.

Policy response

The now former Prime Minister's Serious Youth Violence Summit on 1 April was used to announce a number of policy initiatives, including proposals to introduce a new legal duty on public bodies to raise concerns about children at risk of involvement in knife crime.

In addition, £100m is to be made available to support areas most affected by violent crime to boost police capacity and fund the creation of multi-agency violence reduction units. These will be modelled on the work of Strathclyde Police's Violence Reduction Unit (VRU) which has been hailed for its success in reducing violent crime in Glasgow over the past 15 years. A key element of the VRU has been to adopt a public health approach to dealing with violence. It describes a prevention-focused response that combines enforcement activity with tackling the causes of violence through better education to prevent behaviour being passed on from one generation to the next.

The Association of Directors of Children's Services (ADCS) backs the government's ambition to move to a public health approach, but in a recent discussion paper on youth knife violence it warns that it isn't a "miracle cure", adding that it "requires political buy-in, a long-term commitment to cultural change [and] funding beyond the life of a parliamentary term".

The association argues that there needs to be a more sophisticated and joined-up national response to tackling the issue and suggests lessons can be learned from the multi-agency approaches to reducing child sexual exploitation, the threat of radicalisation and supporting troubled families (see expert view, below).

In April 2018, the government published a Serious Violence Strategy to address the problem. This includes the £22m Early Intervention Youth Fund through which £17.7m has been provided for 29 projects endorsed by police and crime commissioners.

The strategy also includes a new £3.6m National County Lines Co-ordination Centre that launched last September.

Last October, the government launched a 10-year Youth Endowment Fund, which will provide £200m to projects that support interventions steering young people aged 10 to 14 away from becoming involved in violent crime or reoffending.

The Serious Violence Taskforce, chaired by the Home Secretary, meets regularly to oversee delivery of the Serious Violence Strategy. The taskforce brings together ministers, MPs, police leaders and public sector and voluntary sector chief executives.

Legislation accompanying the strategy has seen the introduction of knife crime prevention orders through the Offensive Weapons Act. These can be issued to anyone aged 12 or over who is believed by police to routinely carry a blade. They will place curbs on suspects, such as limiting their use of social media to stop gang rivalries escalating online, and a breach of the order will be a criminal offence that could result in a prison sentence.

Meanwhile, the new £1.4m police social media hub aims to tackle online violence by increasing the Metropolitan Police's capacity to disrupt the online gang activity and work with social media companies to take down violent content.

Local practice

The joint inspectorate's report on the response to gangs and CCE warns agencies "not to underestimate the risk of child criminal exploitation in their areas" after finding evidence that information is not always being shared between safeguarding organisations.

Analysis of local safeguarding arrangements by the children's commissioner revealed a mixed picture with most providing poor quality or incomplete information about the level of risks posed by gangs to vulnerable groups of children. Generally, responses from local safeguarding boards suggest an underestimate of the numbers of children affected.

The report states: "Some London boroughs with high-levels of gang violence estimated gang membership at a dozen children. Some large counties known to be hubs of county lines activity identified less than 20. Even large cities only estimated gang membership in the dozens.

"Almost universally, local safeguarding boards based their estimate of gang membership on the number of children in contact with statutory agencies, normally youth offending teams or children's services. Our responses showed very little attempt to create a population-level estimate of gang members within local areas."

A similar picture emerges in Counting Lives: of the 141 councils that responded, almost two-thirds said they did not have a strategy in place to address CCE or county lines.

Where statutory agencies come across suspected child victims of CCE, they can be referred to the National Referral Mechanism (NRM) to help trigger support and protection action. Although The Children's Society said police and council data on NRM referrals is "patchy", it found more than half of the children referred were because of CCE.

The ADCS says local agencies are often those first to recognise children at risk of gangs or CCE. For example, the Aasha project works on the estates of east London to help engage Bengali young people referred through the NRM (see practice example).

Other schemes are working across council and organisational boundaries to tackle the issue. The St Giles Trust is supporting young people in Kent following a surge in county lines activity there from London gangs (see practice example).

In south Yorkshire, three councils and the area's police force are working together to engage young people in communities where known gangs are active to develop a consistent sub-regional approach to tackling the problem (see practice example).

Such multi-agency and cross-organisational approaches will likely be invaluable as policymakers and safeguarding agencies try to keep up with the changing tactics of gangs.

CCE RESPONSE MUST AVOID MISTAKES MADE IN TACKLING CSE

By Anne Longfield, children's commissioner for England

The criminal gangs operating in England are complex and ruthless organisations, using sophisticated techniques to groom children and chilling levels of violence to keep them compliant.

I am worried that all the mistakes that led to serious safeguarding failings in relation to child sexual exploitation (CSE) in towns and cities up and down the country are now being repeated.

Many local areas are not facing up to the scale of the problem; they are not taking notice of the risk factors in front of them and are not listening to parents and communities who ask for help.

Our recent report, Keeping Kids Safe: Improving Safeguarding Responses to Gang Violence and Criminal Exploitation, estimates there are 27,000 children in England who identify as a gang member, only a fraction of whom are known to children's services.

Some of these children may only identify loosely with a gang and may not be involved in crime or serious violence, but more concerning is the estimated 34,000 children who know gang members who have experienced serious violence in the last year.

We found children with gang associations are far more likely to have social, emotional and mental health issues and more than twice as likely to be self-harming. They are also more likely to be missing/absent from school. Yet despite these known risk factors, less than half of child offenders involved in gangs are supported by children's services.

It is also clear to us that a number of early warning signs of gang-based violence have been on the rise in recent years. Referrals to children's services where gangs were identified as an issue rose by 26 per cent between 2015/16 and 2016/17. Permanent exclusions rose by 67 per cent between 2012/13 and 2016/17, and the number of children cautioned/convicted for possession of weapons offences rose 12 per cent between 2016 and 2017.

The government and local areas need to face up to the scale of this challenge, and ensure the priority and resources are allocated to helping these children, because it is clear to me that we are not doing enough to protect them from harm.

No child should end up as a headline about gangland murder or the subject of a serious case review simply because nobody thought it was their job to keep them safe. Child criminal exploitation needs to be a national priority in the same way as CSE or countering extremism.

ADCS VIEW

DESIGN A PUBLIC HEALTH APPROACH THAT WORKS FOR YOUNG PEOPLE

By Rachel Dickinson, executive director of people, Barnsley Council and ADCS president 2019/20

There are various risk factors that can increase the likelihood of children and young people being drawn into gangs or being criminally exploited, from being out of school, a lack of positive activities in the local area and inequality to poor mental health. Those at risk of gang involvement are not always known to children's social care, or the police, but are usually known to wider services such as schools, which underlines the need for an integrated, multi-disciplinary response.

While there are plenty of local initiatives making a difference at an individual level, we urgently need a whole-system response that tackles the root causes of harm as well as the societal conditions that allow abuse and exploitation to flourish. This will require a radical shift in policy, practice and funding.

The UK government has pledged to adopt the Scottish approach to violence reduction but there is little detail of how this will look beyond a proposed statutory duty on public agencies. It is always possible to improve multi-agency working, commissioning and information sharing locally and we must strive to do so, but the legislative imperatives to have due regard to prevent violence, to protect young people and promote their wellbeing, already exist.

A public health approach to reducing serious youth violence isn't a miracle cure; it requires a long-term commitment and a long-term funding settlement. It should focus on preventing future harm via the provision of help and support at the earliest possible opportunity as well as offering universal, targeted and specialist interventions.

Such approaches do not inhibit the role of policing, particularly in relation to disruption activities, but children's services are best placed to lead a multi-agency endeavour. Stricter laws, longer sentences and the expansion of police powers will not stop young people being criminally exploited nor address their vulnerabilities. There is a wealth of learning for us all to draw on in designing a public health approach; from responses to child sexual exploitation, efforts to reduce teenage pregnancies and first-time entrants to the criminal justice system to the Troubled Families programme.

The first step, which we urgently need to take, is to agree what constitutes a public health approach. A national commitment to early help services and a comprehensive framework that bridges the "cliff edge" of support between children's and adult social care is needed. Other facets of a public health response could usefully include a clear commitment to community policing, to inclusion in schools, a revitalised curriculum, better careers advice, investment in community-based youth work, expanded drug rehab provision for under-18s and better access to adolescent mental health services.

The association recently published a discussion paper on serious youth violence and knife crime which we hope will trigger a thoughtful debate about these issues and our collective responses to them.

FURTHER READING

- Counting Lives Report: Responding to Children Who are Criminally Exploited, The Children's Society, July 2019

- ADCS Discussion Paper: Serious Youth Violence and Knife Crime, Association of Directors of Children's Services, July 2019

- Keeping Kids Safe: Improving Safeguarding Responses to Gang Violence and Criminal Exploitation, Children's Commissioner for England, February 2019

- Protecting Children From Criminal Exploitation, Human Trafficking and Modern Slavery, Department for Education, November 2018

Read more in CYP Now's Gangs and Criminal Exploitation Special Report