Forging Lifelong Links for children in care

Jo Stephenson

Tuesday, November 27, 2018

The Lifelong Links model being tested in England and Scotland aims to establish and rebuild key relationships for looked-after children. Jo Stephenson spoke to authorities trialling the approach.

In May this year, Tom* met more than 35 members of his family - many of whom he'd never seen before.

The orphaned 12-year-old who lives with foster carers helped plan the gathering and decided who to invite as part of the Lifelong Links project aimed at strengthening support networks for looked-after children.

Before Tom embarked on the process, children's services were aware of just eight members of his extended family but afterwards more than 80 living relatives had been identified.

He is now meeting up with some who live locally and is invited to family get-togethers as well as staying in touch with others by phone.

Tom is one of many children and young people benefitting from the Lifelong Links model, developed by charity the Family Rights Group (FRG) and currently being trialled in England and Scotland.

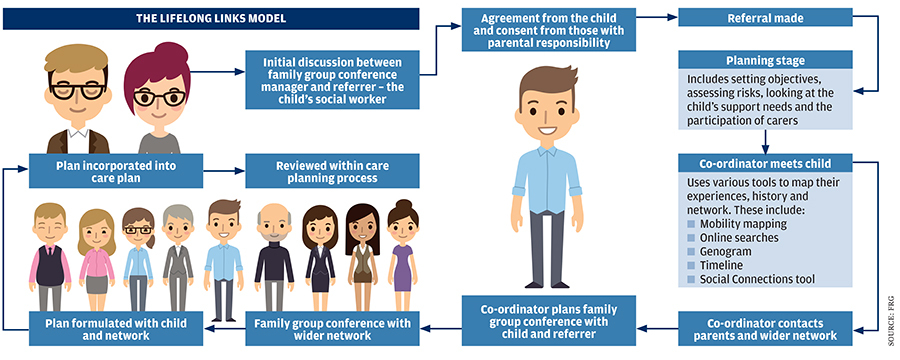

It brings together family group conferences, now an established part of social work practice in the UK, with the newer concept of family finding.

The need to do more to bolster key relationships in looked-after children's lives was one of the main findings from the 2013 Care Inquiry conducted by eight charities, including FRG, explains chief executive Cathy Ashley.

"The overwhelming message was that too often the care system breaks rather than builds relationships so we were extremely keen to think about how you could turn that on its head," she says. "It was apparent care leavers' lack of relationships and support networks was severely hindering them in all sorts of ways - emotionally, practically and financially."

Inspired by the success of family finding in the US and in Edinburgh, which was already doing something similar, FRG worked with local authorities and others to develop a model for the UK (see below).

Crucially this included working with young people with experience of being in care.

"They were very clear it was something they wished they had been offered but also had fears about it being ‘done to them' and lack of control," says Ashley. "So we made sure the model we designed has the young person at the centre all the way through. That means it doesn't go ahead unless they approve and they can stop it at any stage."

Seven local authorities in England embarked on a three-year trial in April 2017, funded by the Department for Education's Children's Social Care Innovation Programme, with five more recently announced. Edinburgh, Glasgow and West Lothian are part of a simultaneous trial in Scotland funded by a number of grant-giving organisations with two more authorities set to take part.

The pilot is for looked-after children aged under 16 and in care for three years or less - based on US evidence that family finding is more likely to succeed for those new to care. In addition, there should be no plans for children to be adopted or return home.

The hope is that making or re-establishing key connections will reduce placement breakdowns, boost children's emotional and mental wellbeing, improve attainment and engagement in education and reduce harmful behaviour as well as improve long-term outcomes like employment - all factors being measured by independent evaluators at the universities of Oxford and Strathclyde.

The majority of children involved in Lifelong Links are aged eight to 16 although children as young as five have taken part. The process involves working closely with children to map out their family and identify relatives and other key people they would like to invite to a family group conference.

Because conferences have a key role in the Lifelong Links process, pilot authorities must be accredited in family group conferencing or gain accreditation within 18 months.

Lifelong Links meetings have a very different feel to a standard conference, explains Ben Carr, Lifelong Links and family group conference manager at Hertfordshire County Council.

"They are different from most children's services meetings because they're not dominated - in terms of numbers - by professionals," he says. "The majority of people there are connected to the young person."

It's more like a "family celebration", adds Katie Jolly, one of the independent family group conference co-ordinators employed by Hertfordshire, who says it is a "privilege" to be part of what are often emotional reunions.

"All our young people have met someone they are related to who they haven't met previously or for a long time so that is a really exciting part of the meeting," she says. "We had one where a dog came - a dog the young person had not seen for three years."

Planning conferences

Lifelong Links family group conferences are held in community venues and planned by the young person. "We have food and quite often play music the young person likes. We take photographs and have a message book like when you go to a party or a wedding," says Jolly.

In Hertfordshire 12 family group conference co-ordinators, two managers and one project officer have been trained in Lifelong Links. The goal is to work with 65 children and young people in the first year of the pilot, 75 in the second and 85 in the third.

Meetings follow the same format as regular conferences in that they start with introductions and information sharing.

"We invite the young people to talk about things they like so family members can get to know a bit about them, their hobbies and what they like doing at school," explains Jolly.

"The social worker will then talk about how they are getting on - in school, in their placement, emotionally - and then we have private family time where we ask the family what they would like to offer the young person as a realistic long-term offer."

The meeting is a chance for people to commit to a level of support they're comfortable with, whether that is simply sending Christmas and birthday cards, phone calls, invites to family events or regular face-to-face contact. This is written up into a plan, which will become part of a child's care plan.

It is early days and trial sites are at different stages of development but the message from practitioners seems to be positive.

"It just made sense to me," says Debbie Marks manager of Devon County Council's Family Group Conference Plus service, which aims to work with 75 children and young people during the pilot.

"Obviously people had anxieties about how it would work, whether it would benefit young people but that didn't detract from it sounding like a really good idea."

In Devon the pilot is being delivered by a lead co-ordinator and four others trained in Lifelong Links. The authority has held 11 conferences for young people so far and the results are "very exciting", according to Marks.

"We feel confident it has made a difference to their sense of identity, self-esteem and sense of belonging and all those things have to be positive," she says.

When it comes to the practicalities of delivering the model she admits the authority had not anticipated the amount of travel and time involved in reaching out to far-flung family members and in working with the young person at their own pace - checking in with them all the way through the process. However, none of this has proved "insurmountable".

Co-ordinators in Devon report bringing carers and wider family together has helped children feel more settled and "increased their sense of belonging in their foster family".

It has also provided extra support for foster carers who now have the backing of biological families. "There is more communication and things are more joined up in general," says Marks.

Key issues include an understandable reticence on the part of some social workers, managers, carers and parents worried about the emotional impact and potential risk of destabilising placements.

What happens if no one comes forward? How do you prepare already vulnerable young people to deal with potential disappointment?

The fact is many young people are already searching for relatives in ways that may be unsafe or make it more likely for them to experience rejection, says Ashley.

She gives the example of one young offender taking part in the scheme who had previously turned up on the doorstep of a family member unannounced and proceeded to be quite aggressive. "The response was to completely push him away," she says.

Ashley suggests the desire to protect young people may even put them at more risk in the future if they emerge from care rootless and without people they can turn to for help.

Another theme that has emerged is a tendency to assume "we're a good authority so we do this anyway", she says. However, all pilot sites are reporting finding family members and other key contacts that had not previously been known about or even considered as important in a young person's life.

"We have been surprised at just how many fathers as well as wider paternal relatives have been found and connected through this process," says Ashley.

"We knew about fathers too often being pushed out from decision making but were surprised at how many children had absolutely no connection with their father for a very long time and how many fathers didn't even know their children were in care."

Forging positive relationships

Some did not even know whether they were the father or not. The Lifelongs Links process has led to several DNA tests being done, which has lifted a huge burden of uncertainty for children and dads alike and led to positive relationships being forged.

Ashley recounts the story of one young man in Scotland who was keen to know his father. All he had was a photo of his mum and dad's wedding with dad's face cut out.

"So this child was holding on to this photo without a face," says Ashley. "In that case - although it wasn't the primary aim at all - it looks like the child will end up moving in with the father."

In cases where it is harder to trace people or get them involved there is evidence the process itself can help young people make sense of their family history and muddled childhood memories. Far from destabilising placements, it appears to help even those with the most complex needs settle down.

Where there are concerns - especially if a young person is involved with child and adolescent mental health services - then these need to be worked through, explains Margot Thomson, team leader for family group decision-making in the north east of Glasgow.

Her team of four Lifelong Links trained co-ordinators hope to work with 25 children for each year of the pilot.

"We would not want to destabilise a placement and recalling family members or feeling bereft of family can upset children," she says. "But it's not the case that we wouldn't go ahead - we would look at how to support that child and foster carer."

Ensuring robust support for young people going through the process and that they are properly prepared is key. This includes preparing young people for the fact the people they want to see may not be in a position to come forward.

"It is about helping the young person understand it not about them per se but may be about the other person's own personal circumstances," says Hertfordshire's Ben Carr.

At the same time it is important not to give up too easily when it comes to tracking people down and getting them involved, says Devon's Debbie Marks.

"Persistence is one of the things we have learned from the other sites and our own experience," she says. "It is about really knowing - not just thinking you know - whether one of the identified links is interested or not.

"We tend to think ‘We have tried this, tried that and haven't had a response so they're not interested' but that isn't always the case. Sometimes families don't know how to respond."

When children enter care ties with their parents may be severed and often that means relationships with wider family are severed too.

So going back to people some time down the line to see if they have anything to offer the child "is a big ask in some respects", points out Glasgow's Margot Thomson.

"It is about opening up that dialogue with people but certainly not putting pressure on anybody," she adds.

Extended family contact

Often extended family members believe they are not allowed to have contact. Thomson gives the example of one boy who had multiple placements before ending up in a residential school.

Through Lifelong Links two of his sisters were located with one caring for an older brother with learning needs.

Despite the fact they had been through the care system themselves and stayed in touch with each other they didn't think they would be allowed to see their brother but "absolutely jumped at the chance" when approached.

Eight months down the line and they are now regularly meeting up and the hope is the boy, who is nearly 16, may now have other options when he leaves care.

Challenges for those involved in the pilot include looking at ways to ensure no child is excluded from taking part, including those with severe disabilities who may be non verbal and unaccompanied asylum-seeking children.

Ashley admits the high turnover in social work departments has also proved problematic and has had an impact on referrals.

Key lessons learned include the importance of consent - including consent from parents who may not be having contact with their children - and the need to consult, involve and support foster carers, who in turn have a key role in supporting young people.

It is also important independent reviewing officers are on board as they oversee children's care plans and can ensure the Lifelong Links element is incorporated.

Anecdotal evidence and case studies from pilot authorities suggest the process has the potential to transform young lives.

The project is also having a wider impact. Prompted by Lifelong Links, Glasgow now has an administrator in place who undertakes extended family searches for children in the trial but also for those who are the subject of standard child welfare family group conferences, including those on the edge of care, and to inform life story work for other children in care.

So far searches for 199 children have resulted in an additional 3,962 family members being found - alongside the 1,257 already known about.

As part of the project the FRG worked with the Rees Centre in Oxford to develop a way of measuring key relationships in young people's lives after discovering there wasn't really a suitable evaluation tool already out there.

It is clear the Social Connections tool - which prompts questions about who young people have to turn to, who looks out for them and takes pride in their achievements - may prove important in social work practice in general, says Ashley.

The project has also had an influence on foster carer recruitment in some councils who are now placing more emphasis on finding people who understand they have a key role in helping young people stay connected with wider family networks and don't feel threatened by that.

Interim findings from the pilot in England are due to be published in March 2019 with a final evaluation report in March 2020. Interim findings from Scotland are due in autumn 2019 with a final report in summer 2020.

Perhaps in the future, the Lifelong Links process will be something offered to all children when it becomes clear they need a long-term care placement, suggests Hertfordshire's Katie Jolly.

"In an ideal world this would be work done with them then and not something separate that happens afterwards," she concludes.

*Name changed

BRIAN'S STORY LOOKING FOR ‘THAT ONE GOOD PERSON'

When the Lifelong Links co-ordinator first met with 12-year-old Brian*, his first reaction was: "I don't think anyone is going to want to see me."

As the result of an early childhood scarred by domestic violence and parental substance abuse, he and his sister were placed with an aunt.

Then it emerged Brian had engaged in sexually harmful behaviour with another child in the family. He was removed from the home and is currently living in a residential unit.

Following the move he stopped attending school and became depressed and at the point of referral to Lifelong Links was clearly struggling with rock bottom self esteem and a lack of direction in life.

A "mobility mapping" exercise where Brian drew all the different houses, schools and care placements he'd had showed just how unsettled his life had been. When it came to making friends, Brian explained: "There was no point - you just get moved anyway."

However, there are signs the Lifelong Links process is having a positive impact on this isolated young man. The manager of Brian's residential unit reports he always seems happier after sessions while his social worker agrees he is benefiting.

His co-ordinator has a list of people to contact including a former foster carer who was aware of the sexual misconduct and a teacher who was supportive.

Brian, who occasionally visits his dad in prison, had not had contact with his sister for some time but this resumed during the Lifelong Links process and he also started going to school again.

Ultimately he hopes the process will help him find "that one good person" who cares about what happens to him and is willing to offer some level of support while he is in care and beyond.

*Name changed

PILOT AUTHORITIES

England

- Camden

- Coventry

- Devon

- Hertfordshire

- Kent

- North Yorkshire

- Southwark

NEW

- Central Bedfordshire

- Doncaster

- Rotherham

- Kensington and Chelsea and Westminster

- Stockport

Scotland

- Edinburgh

- Glasgow

- West Lothian

NEW

- Two more to be announced