A public health approach to youth violence

Tom de Castella

Tuesday, September 25, 2018

With violent crime on the increase in England, Tom de Castella asks what children's services can learn from the public health model that originated in the US and has reduced youth violence in Glasgow.

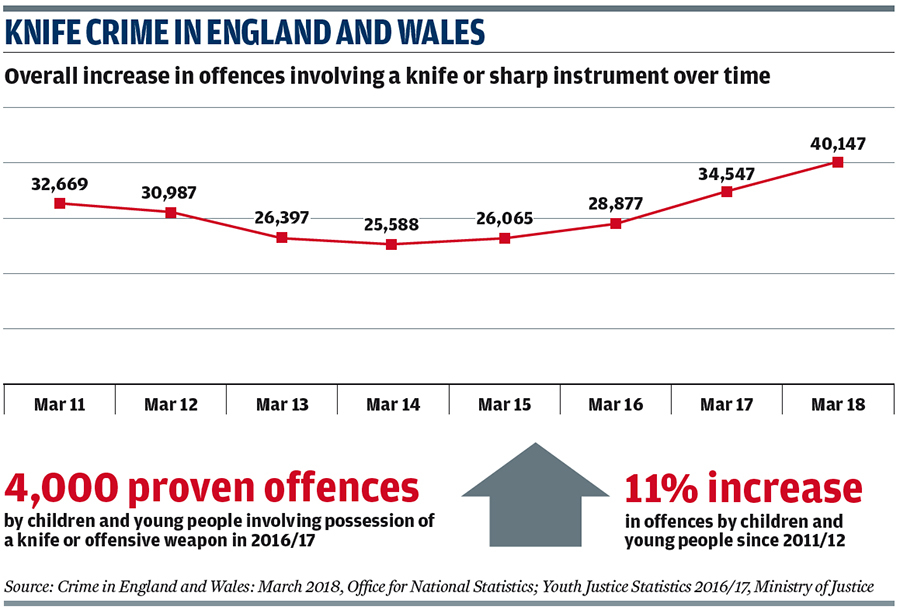

Violence is on the rise in Britain. And in many cases it is young people on the frontline as both victims and perpetrators. Last year the number of teenagers murdered in London passed 25 for the first time since 2008. At the current rate - 21 dead at the time of writing - that figure looks set to rise again this year.

The increase in violent crime is greatest in London but it has been going up across most of the UK, excluding Scotland, for several years. The response from politicians and the media was at first to look for conventional explanations: falling police numbers, violent lyrics in drill music - an aggressive form of rap music - and restrictions on the use of stop and search.

But the scale of the problem - with an average of 750 knife crimes each week in England and Wales - means a growing number of public figures are calling for a radical new approach.

It is called the public health model. Instead of treating young people stabbing each other as a criminal justice problem this approach sees it like a contagious disease. At first it is a bit of an imaginative leap to see a teenager stabbing someone at the bus stop like the spread of Ebola across West Africa. But that is exactly what this is, says Charlie Ransford, a director at US non-governmental organisation Cure Violence, and one of the world's leading experts on the public health model (see below).

The idea of fusing violence with public health can seem confusing, he admits. But the concept is straightforward - violence breeds violence. "People understand that children who grow up in abusive families are much more likely to be abusive themselves," he says.

With a cholera or HIV epidemic it is about trying to stop the spread of infection. With street violence it is the same - trying to prevent people's exposure to violence, to stop retaliation and counter retaliation. Young people are more impressionable and therefore particularly prone to violence, says Ransford. Rather than blaming the individual, it is more helpful to see violence as committed by people with a history of trauma, he explains.

But what does this mean in policy terms? "It's really about hiring workers who can identify the people at highest risk," he says. "Then they can talk to them from a place of understanding, can talk them out of doing something and talk them into getting help."

At the moment, the high-risk people in London and a lot of other cities are not being touched, he maintains. There are youth outreach programmes but they deal with a broad range of issues - drugs, family breakdown, unemployment and support for those coming out of the criminal justice system. "If you want to reduce violence, then you need to hyper-focus on the people doing violence as opposed to just anyone needing help," says Ransford.

Mediation and risk reduction

A key plank of the public health model is training people in methods of mediation and risk reduction specific to violence reduction. Equally crucial is getting the right people to do the outreach - someone who has credibility with young people and comes from the same community.

The public health model has been backed by Sarah Jones, Labour MP for Croydon Central and chair of the all-party parliamentary group (APPG) on knife crime, and Labour MP Chuka Umunna who is part of the government's Serious Violence Taskforce. Meanwhile, the Youth Violence Commission's interim report, published in July, called for the government to develop a national plan for the implementation of a public health approach to youth violence, which could be adapted to the needs of each region. The reason the approach has received such high-level backing is that the evidence suggests the public health approach works.

Evaluation of programmes in the US typically show a 50 per cent reduction in shootings, according to Ransford. A cost-benefit analysis of hospital-based interventions - one form of public health approach - published in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine in 2015 also suggested it could save money.

Scotland's story is perhaps the most powerful endorsement. In 2005 Strathclyde Police set up Glasgow's Violence Reduction Unit (VRU). This was a team tasked not with solving crime but preventing it. In the previous year the city had 40 murders, which was twice the national average at a time when homicides were at their highest level for a decade.

In 2006, the unit took on a remit for the whole of Scotland. Since then violent crime in Scotland has almost halved and crime involving a weapon has fallen by two thirds.

Karyn McCluskey, founder and former director of the VRU, is proud of what they achieved. She says the approach can work anywhere, whether in London, a rural area or deprived parts of Australia - she has just returned from advising Aboriginal communities.

Focus on violence, not weapons

Her first piece of advice is not to obsess about weapons. "I never talked about knives. I talked about violence." It doesn't matter if it is guns, knives, or fists. It's all violence and has to be addressed in the same way, she stresses.

Second, work with everyone. The programme broke up Glasgow's long-established gangs by offering members an alternative to the violent lives they were living. It also worked with schools to target those most likely to become involved in violence. McCluskey believes in "zero exclusion" - you shouldn't exclude kids who don't want to be excluded, she says. Primary school teachers are also a great resource - they are usually able to identify children likely to get into trouble with 90 per cent accuracy, she says. If you work with primary schools and help parents to be better at bringing up children you have got the "magic" formula.

Another key thing to bear in mind is that scaring young people about violence doesn't work, McCluskey believes. "You need to give them hope," she says. Stop and search can work in specific instances but only in the short-term. In Scotland they mentored young people as "bystanders" who could intervene and prevent violence. It made young people part of the solution rather than the problem.

Finally, you need time and political backing. It took until 2012/13 in Scotland for the full benefits to be realised - seven years after the unit was first set up. Politicians have to let you get on with it beyond a four-year term, she says. One way to do this is to bring the public with you. To do this you need to engage with the media as they will reach far more people than you can, she says.

Kenny, 23, from Elephant and Castle was one of the young people who listened to Ransford and McCluskey speak at a joint evidence session hosted by the Youth Violence Commission and APPG on knife crime at the House of Commons this summer. He saw his brother get stabbed seven years ago - something he will never forget. While he gets the concept of violence as a disease and can see it is a powerful metaphor to use, he worries it may remove some of the personal responsibility involved in committing violent acts. "Everyone has a choice," he says. "As much as people can blame the government or police, you don't have to carry a knife."

Parts of England and Wales are already putting parts of the approach into practice. In Cardiff and Nottingham projects in hospital (see case studies) are trying to identify when victims of violence are admitted to accident and emergency departments and then working with them to prevent repeat violence. In London, boroughs like Hackney and Lambeth are also embracing the public health model.

Public agencies in Lambeth are in the process of developing the borough's first Tackling Violence Against Young People strategy. Designed to be shaped by the local community - including young people.

Hackney's multi-faceted approach includes an Integrated Gangs Unit, which brings police, the local authority and other partners together in the same building and includes outreach support for young people provided by youth workers within the team.

Charity StreetDoctors has been brought in to run workshops to equip young people at high risk of violence with the first aid skills and confidence to act in a medical emergency. StreetDoctors' young medical volunteers challenge attitudes to violence and treat young people as potential lifesavers capable of making positive choices and helping others.

Another programme aims to boost outcomes and aspirations for young black men by training them as peer leaders. Last month, the mayor of London Sadiq Khan announced he would establish the capital's own Violence Reduction Unit to include public health, police and local government staff, with £500,000 of initial funding.

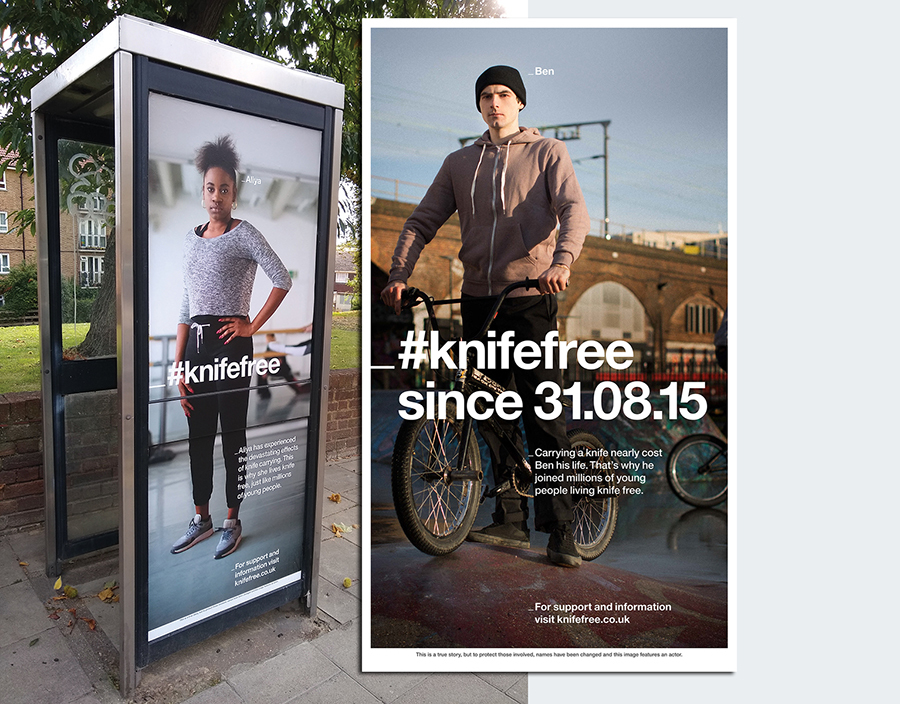

But will the public health approach receive top-level backing? In April the government published its Serious Violence Strategy. It included a £22m early intervention fund, continued backing for the anti-knife crime community fund, and money for young people's advocates to help gang-affected young people. It was accompanied by a hard-hitting advertising campaign #knifefree, featuring real-life stories of young people who had turned their back on knife crime.

Encouraging signs

Despite there being no mentions of the public health approach, Ransford sees encouraging signs in the strategy. "There are many indications in this plan that the Home Office plans to incorporate more approaches that understand violence as a health issue."

There is increased work in hospitals and the expansion of charity Redthread's Youth Violence Intervention Programme (see case study), references to being "trauma informed" and using "teachable moments".

However he finds it "troubling" that the Home Office is unwilling to adopt the language of violence as a disease. "It requires more than just programmes, but also an approach and perspective that is based on the understanding of violence as a contagious problem," he says. "To achieve safer and healthier communities, we need leaders who can help guide our understanding of violence."

The idea has high-profile backers. The question now is if it remains just that - an idea - or whether it can kickstart practical policies to reduce violence on Britain's streets.

TREATING VIOLENCE AS A CONTAGIOUS DISEASE

By Charlie Ransford, senior director of science and policy,

Cure Violence and Dr Gary Slutkin, founder and chief executive,

Cure Violence

Over many years and hundreds of studies, science has shown violent behaviour is contagious. In fact, violence has been found to fulfill the criteria of an epidemic disease, including clustering, spread, and transmission between individuals. Acknowledging that violent behaviour is acquired through exposure and trauma allows us to see things differently. Every response to violence should be based on this scientific understanding.

Because violence is contagious, violence is fundamentally a health issue and health approaches are needed to detect, interrupt, and prevent it.

The Cure Violence Health Model came out of the experiences of Dr Gary Slutkin in the management and reversal of epidemics such as tuberculosis, cholera, and HIV/Aids. The model is based on established methods that have been shown to control other epidemic diseases. It is derived from a synthesis of the fields of epidemiology, infectious diseases, behavioral science, social psychology, and neuroscience as well as informed by the experiences of people in affected communities.

The Cure Violence model applies the same three strategies used by the World Health Organisation for reversing the spread of infectious diseases:

- Interrupt transmission

- Prevent future spread

- Change group norms

To interrupt transmission, health workers detect active cases and stop transmission to others. For violence, an active case can be someone who wants to retaliate for a previous act of violence or is very angry because he feels disrespected and is contemplating violence. In these cases, a worker can detect the conflict and neutralise the tensions that lead to violence or change the thinking so violence will not be used.

To prevent future spread, health workers find those who have already been exposed to the disease and treat them before they can spread it further. For violence, workers find those persons that are most exposed to violence and at most risk of future involvement and work intensively with them to change their behaviour, including addressing the risk factors influencing that behaviour.

To change norms, health workers challenge unhealthy or harmful norms and replace them with positive and healthy norms. With violence, as with most epidemics, this is done by spreading information through public education, specific events, and other activities. The spread of information and skills makes group immunity possible. This is where a whole population becomes resistant to a disease.

A central characteristic of the Cure Violence Health Model is the use of credible messengers as workers - individuals from the same communities who are trusted and have access to the people most at risk of perpetrating violence. These can include people who have formerly been involved in violence but have changed their behaviour. They are able to talk about violent behaviour credibly and persuade high-risk individuals to resist behaving violently. Intensive and very specific training is required, but hiring the right workers is essential to get the access, trust and credibility required for the job.

The Cure Violence approach has been implemented in more than 100 communities across 15 countries. The model has been externally evaluated several times, with each evaluation showing large, statistically significant reductions in gun violence. Studies by Northwestern University and Johns Hopkins University showed 41 to 73 per cent reductions in shootings in neighbourhoods in Chicago and as much as a 56 per cent decrease in killings in Baltimore. Meanwhile an evaluation by John Jay College found reductions in shootings in New York City of up to 63 per cent. International adaptations of the Cure Violence model have also had large reductions in violence, including an 88 per cent reduction in shootings and killings in San Pedro Sula, Honduras; a 67 per cent reduction in shootings in Port of Spain, Trinidad; a 29 per cent reduction in attempted killings in Cape Town, South Africa; and more than 50 per cent reduction in killings in several sites in Ciudad Juarez, Mexico.

To say violence is an epidemic is not a metaphor. We have highly effective and time-tested public health methods used worldwide to stop the spread of contagious diseases. Yet violence is the only health epidemic not being managed primarily by the health sector. It is high time that changed.

CARDIFF HOSPITALS SHARE DATA ON VIOLENCE

Twenty years ago, Jonathan Shepherd, a surgeon in Cardiff discovered the police were not aware of two thirds of the violent incidents leading to hospital admissions.

"The implication was that A&Es were hugely important sources of information not known to the police," he says. So he set up the Cardiff Violence Prevention Board to fill the information gap.

The first step was to get receptionists at Cardiff's A&Es to ask a series of questions of people injured in violent attacks: Where did it happen? What was the weapon? How many people hurt you? - a question particularly important when it comes to tackling gang activity - as well as basics such as the time and date of the violence.

The hospital anonymised the data and shared it with the violence prevention board. They then worked with police and other partners to stop violence from happening. New CCTV cameras were installed, police patrol routes changed, tougher glasses were put into certain bars, licenses were changed.

While the night time economy accounted for many injuries, the A&E data showed schools were unaware of violence taking place. So in 2009 hospitals set up a system whereby a letter was automatically sent out to the school nurse whenever a child was admitted to hospital with a violent injury.

While knives account for a small proportion of Cardiff violence, the model is now being used in all 29 A&Es in London. Police knife violence data can appear sketchy on a map, Shepherd says. But add in the hospital data and the "hotspots become hugely clearer," he explains.

The project has been evaluated with findings published by the British Medical Journal and others. The headline finding is that using the Cardiff model can cut violence by 40 per cent.

NOTTINGHAM REDUCTION IN RETURNS TO CASUALTY

Nottingham's Queen's Medical Centre is the main trauma centre for the East Midlands. Surgeons there had become used to seeing the same young people attending the casualty department as victims of knife crime and other forms of violence.

They contacted youth work charity Redthread to see what could be done. In March, the Youth Violence Intervention Project began at the hospital. Based on the charity's successful London schemes, the three-year pilot project supports victims of youth violence aged 11 up to their 25th birthday.

Doctors and nurses in A&E are there to save lives in the moment - they are not there to change lifestyles. And that is where the project's work with young people comes in, says David Bentley, Redthread's team leader at the hospital.

"We ask if they want help or guidance to try to help them avoid coming back into hospital." A key question that the youth workers ask is: "How do you feel towards the person who's done this to you?"

The young people are usually very open in their response. "Often they'll say ‘I'll get them back as soon as I get out.'" It's then up to the youth workers to try to help them recognise that more violence may not be the solution.

Redthread staff have an office in the hospital. They wear bleeps that go off when a young person is in the hospital's resuscitation bay.

Staff also have access to relevant medical records. After discharge, Redthread supports the young person in the community but the main focus is on referring them to specialist organisations such as Victim Support, housing organisations and counselling services.

Since going live the team has met 95 young people. Less than two per cent have re-attended for violent incidents so far. The project is funded by charity the Health Foundation with some money from Nottinghamshire's police and crime commissioner.