Schools key to obesity response

Suzanne Gomersall

Tuesday, June 26, 2018

Policymakers must improve cooking lessons for primary pupils to cut obesity levels, warns academic.

Primary school children are taught - as part of personal, social, health and economic (PSHE) education - about the many dangers they may face growing up: stranger danger, bullying, substance abuse, sex and relationships and, most recently, staying safe online.

However, inexplicably, we do not feel able to tackle obesity, which has risen from six per cent of the population in 1980 to 27 per cent in the UK today.

One in 10 British children are already obese when they start primary school, and this figure doubles by the time they leave at 11.

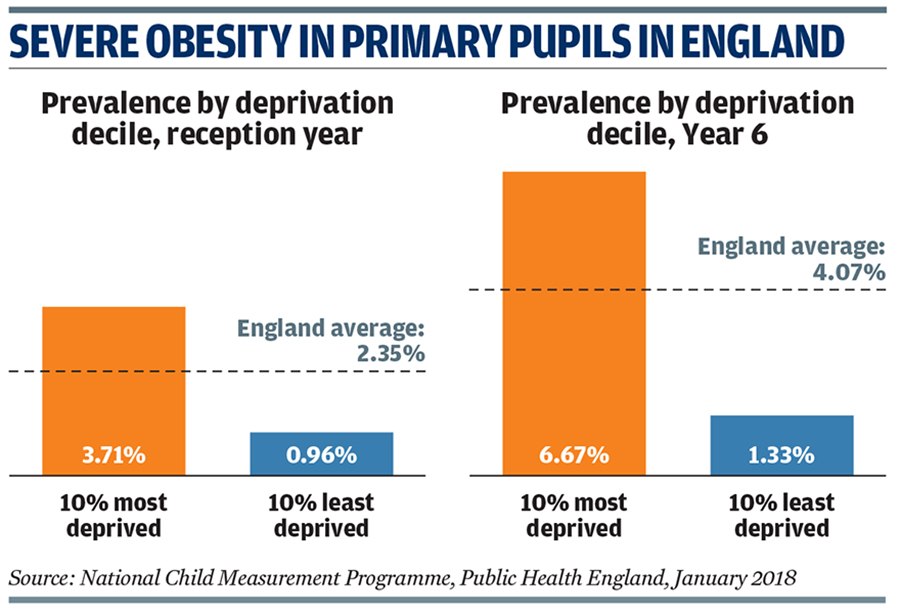

For the first time, the annual National Child Measurement Programme has released official data on "severe" obesity. This shows that children living in the most deprived homes and from minority ethnic backgrounds have the highest rates of severe obesity (see graphics).

If for many years medical experts have believed there is an urgent need to initiate prevention and treatment of childhood obesity - and that children should be targeted as the priority population for intervention strategies - what have policymakers and school leaders done to tackle this in primary schools?

Since the new Primary National Curriculum was introduced in 2013, cooking and nutrition education has become part of the statutory design and technology programme of study.

It states that children from key stages 1 to 3 "should be taught how to cook, and apply the principles of nutrition and healthy eating". This conveys a clear message to head teachers that healthy eating is a significant part of the curriculum and an inspection criteria.

Ofsted inspectors should look at the "breadth and balance of the curriculum, of which practical cookery is now a part".

Inspection failings

In 2014, Ofsted wrote a letter to the all-party parliamentary group on school food to outline its commitment to prioritising healthy eating in inspection.

However, through the contact Nottingham Trent University has with hundreds of Ofsted-inspected schools every year, it is clear that children are not receiving regular cooking and nutrition lessons, and yet this is not getting picked up.

If Ofsted inspectors are actually checking and reporting on this, why isn't it being mentioned as an area for schools to improve?

In May, the health select committee report Childhood Obesity: Time for Action found that our concerns were reflected nationally.

It stated there is "no convincing evidence that any of these school-related measures had been implemented in an effective or holistic manner".

So plans are in place for reform, but schools are still not being held properly accountable for their teaching of nutrition.

We cannot leave this to children or parents to solve - many do not have the knowledge, skills and understanding to make the right choice.

Policymakers and school leaders need to put the right measures in place to equip children with the skills of how to choose, prepare and cook healthy ingredients to make healthy dishes to feed themselves and their families.

Here are four key measures to incentivise change.

Measure 1

Children should receive the regular cooking and nutrition sessions in school to which they are entitled, in line with the statutory Design and Technology curriculum. Just providing children with a healthy breakfast or providing free school meals to all children under the age of seven has been proven to be ineffective - they need educating and taught the skills to prepare and cook healthy dishes from when they enter school.

Measure 2

The Ofsted framework needs to value and assess how well cooking and nutrition is being taught across the schools, as well as breakfast and lunchtime provision. This is supported by the health committee report, which states: "We urge a full and timely implementation of all of the measures contained in the first Childhood Obesity Action Plan. School food standards should be mandatory for all schools, as should the Healthy Rating Scheme."

Measure 3

Since 2013, the government has provided schools approximately £16,000 a year through the School Sports Premium. Each year, schools must justify how they have spent this money, but I am yet to hear of a primary school being taken to task by the authorities for the lack of cooking and nutrition provision. The premium should be reworked and renamed to include spending to support the teaching of cooking and nutrition.

Measure 4

The government has recognised that schools need additional funding to support disadvantaged children by providing them with pupil premium funding. As a greater number of children from disadvantaged backgrounds are more likely to become obese - as their families are unwilling or unable to spend as much of their disposable income on fresh food - then it seems sensible to target some of this funding to support the introduction of practical cooking sessions. Fundamentally though, for these children and their families, it is key that they understand that cooking meals using fresh ingredients is both cheaper and more nutritious than buying ready meals or "fast food" to have a lasting impression.

- Suzanne Gomersall is senior lecturer at the Institute of Education, Nottingham Trent University, and a former assistant head teacher