How Ofsted's SIF has changed the children's services landscape

Neil Puffett

Tuesday, January 2, 2018

Under Ofsted's single inspection framework, the number of children's services rated "inadequate" has doubled, prompting criticism it raised the bar too high. Leaders assess its legacy and what it will mean for the future.

Ofsted's single inspection framework (SIF) cycle has been completed. Launched in October 2013, the SIF was intended to be completed within three years, but difficulties getting all 152 councils inspected in time led to this being extended by a year.

From January 2018, it will be replaced by a supposedly less demanding regime, designed to reflect the pressures councils face as a result of funding cuts.

Ofsted has said the new system - the inspections of local authority children's services (ILACS) framework - will be more proportionate, risk-based and flexible than before, allowing it to prioritise inspection where it is most needed.

What children's services landscape does the SIF leave behind and what will its legacy be?

All the talk when the SIF launched was about Ofsted "raising the bar" for children's services inspections, and the results bear this out - with more children's services departments receiving lower gradings than previously.

Overall, a total of 30 councils have been rated as "inadequate" under the SIF, with a further 68 rated "requires improvement".

By comparison, under the previous inspection framework, 17 local authorities were judged inadequate for safeguarding - this rose to 20 after a handful were downgraded upon re-inspection.

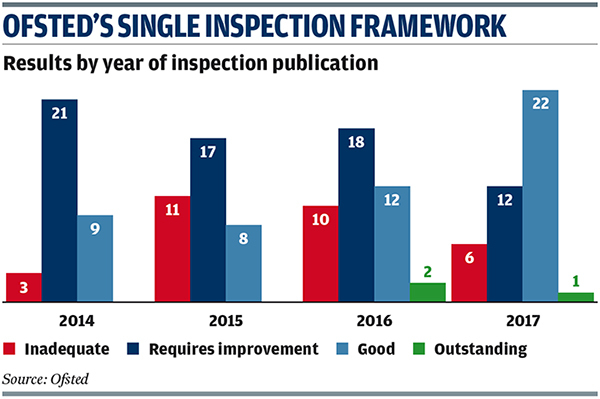

However, results under the SIF have improved over time. Of the 39 inspection results published in 2014, three-quarters received an inadequate or requires improvement rating.

This year, of the 41 councils inspected, the proportion of councils rated inadequate or requires improvement has dropped to 44 per cent.

Whatever the reasons behind the upward curve, Eleanor Schooling, Ofsted national director of social care, says evidence of improvement from re-inspections of inadequate councils - combined with the fact that one in three children's services are now rated "good" or "outstanding" - indicates that "positive progress" is being made (see box).

However, Andrew Webb, Stockport Council's director of children's services and former president of the Association of Directors of Children's Services (ADCS), remains unconvinced that the framework is a reliable way of appraising children's services.

A vocal critic of Ofsted, Webb claims that the methodology of the SIF, its predecessor the safeguarding and looked-after children (SLAC) regime, and its successor the ILACS, measure different things in different ways.

Moving the goalposts

Rather than "raising the bar", Ofsted has actually "moved the goalposts", he says.

If this were the case, a claim that is strongly disputed by Ofsted, it would make sense that results improved as the cycle proceeded - as councils became more knowledgeable about what was required.

Webb says the methodology of the SIF, its predecessor and its replacement are sufficiently different to "render meaningless" any attempt at comparing the performance of a single local authority or local safeguarding system over time.

He adds: "The only checks to which the SIF is ever subjected are through internal moderation. Despite the impact and importance attached to this inspection process, Ofsted simply marks its own work, so any judgments it makes about what it has found should be treated with caution."

There are also concerns about the impact of judgments and the way they are perceived. The SIF replaced the old "adequate" rating with "requires improvement".

ADCS says this change, and the nature of labelling complex children's services structures with a single word judgment, have had profound implications for the sector.

Steve Crocker, chair of the ADCS standards, performance and inspection policy committee, and director of children's services in Hampshire and the Isle of Wight, says the sector has developed its own terminology to distinguish the different types of requires improvement rating - a "strong RI" for an area verging on "good" or a "solid RI" for an area further back.

"The problem is that the ubiquitous use of the grade, particularly in the first two years of the inspection schedule, and the ambiguity of meaning - we all require improvement - has led to directors questioning the usefulness of the grade," he says.

The ADCS has consistently called for Ofsted to adopt a narrative judgment.

"Single-word judgments tell a partial and excessively negative story, which runs the risk of weakening the very services the regulator seeks to improve," Crocker says.

"The instability caused by a ‘poor' inspection judgment - and the requires improvement grading is too often perceived as poor - can compound issues further.

"One word alone cannot do justice to the work of thousands of professionals working hard day in, day out to keep children safe."

What is without doubt is that the SIF cycle has coincided with greater levels of government intervention in children's services departments deemed to be failing.

Colin Green, children's services consultant and former DCS in Coventry, says SIF ratings have been central to government intervention in children's social care services.

Outsourcing services

"Any local authority judged inadequate for the inspection categories of ‘children in need of help and protection' and ‘children looked after and achieving permanence' has been at high risk of being required to outsource their children's services," he says.

"This outsourcing was a purposeful attempt by the government to increase the variety of providers in children's social care services and to tackle perceived weaknesses in local government's delivery of these services.

"It has given rise to a variety of structures outside the local authority. Children's trusts have been established by local authorities sometimes in partnership with an existing trust such as Together for Children, established by the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames.

"All the new arrangements have been not-for-profit. Whether the huge effort and costs involved in setting up new structures leads to sustained long-term improvement for children's services we have yet to see."

Where the local authority failure has been deep and long lasting - such as in Birmingham and Doncaster - the opportunity for a new start and the energy and resources brought by the development of a trust solely focused on children's social care "has been helpful", adds Green.

Concerns have also been raised about the cost of inspection.

Webb estimates that the inspection process cost his council in excess of £200,000, claiming this makes it "phenomenally wasteful of scarce resources".

Green says the cost of "lost opportunities" also needs to be considered.

"Fear of innovation and how Ofsted will view change and risk taking has inhibited service development," he says. "The safe option is to do nothing radical before an inspection is due." However, he says the SIF has also acted as a catalyst for councils to invest more in children's services.

"Nearly all councils judged inadequate have spent millions more, not least on more social workers to reduce caseloads, so their social workers can do a better job," he says.

"It is salutary that a ‘good' council such as Hampshire plans to spend an additional £6.5m on recruiting 100 children's social workers.

"How many local authorities will be able to afford this level of investment, especially in the most deprived areas where need is greatest?"

Ofsted View: ‘Love it or loathe it, the SIF has given us a comprehensive baseline from which to move forward'

By Eleanor Schooling, national director for social care, Ofsted

The end of 2017 marked two milestones for children's services inspection: the completion of the single inspection framework (SIF) programme and the launch of its replacement - the Inspection of Local Authority Children's Services (ILACS) system.

As Ofsted's annual report published last month shows, good and outstanding services for children are achievable. Over a third of local authorities are now rated "good" or "outstanding" and this is largely down to the hard work of dedicated social work professionals.

The SIF had one central aim - to provide the most comprehensive look at the whole of a child's journey that the sector had seen. It was supported by important figures such as Professor Eileen Munro, and it raised the bar.

Intentionally broad, deep and forensic, the SIF highlighted strengths and weaknesses across all areas of practice - from the front door of social care to the longer-term outcomes for those who have left care. With up to seven inspectors on site across three weeks, it was a mammoth undertaking, both for inspectorate and inspected.

Love it or loathe it, we have seen local authorities respond positively and step up to the plate. Some areas that require improvement to be consistently good are now demonstrating areas of excellent practice. Other higher performing areas have built partnerships and models of support for local authorities that are doing less well - we are now seeing the difference this is making. This is progress.

The SIF has given us a comprehensive baseline from which to move forward. It was intentionally a one-size-fits-all inspection, but there is now a place for a more flexible, risk-based and proportionate way of looking at how children's services departments are performing.

This is why we have developed the ILACS system, which will officially begin in January. A more nuanced and bespoke approach, ILACS will use intelligence and recent inspection judgments to decide how and when a local authority is inspected, and to determine the contact and support it receives in between visits. Importantly, the new system will allow us to prioritise our attention where it is most needed.

Crucially, more frequent contact between Ofsted and local authorities will help us to catch areas before they fall.

Local authorities will share their own self-evaluation, followed up with an "annual conversation" with Ofsted that will help them take a critical look at their own performance and articulate what they think is working well for children.

Where self-evaluation identifies weaknesses in practice and the local authority has credible plans to take appropriate action in response, we will treat this as effective leadership rather than an automatic trigger for an inspection or focused visit. It is important that such areas are given time to take action.

As ever, children and their experiences are at heart of this new approach. However, we also hope the ILACS system helps - even in a small way - to lessen the cliff-edge associated with inspection and the implications this has for social work staff on the ground.