How programme ends cycle of family violence

Emily Rogers

Tuesday, January 2, 2018

Professionals intervene to help repair and improve family relationships when young people have perpetrated abuse against their parents.

PROJECT

Respect Young People's Programme

PURPOSE

To prevent 10- to 17-year-olds using violence and abuse within family relationships

FUNDING

£789,419 from 2012 to 2016 from the Big Lottery Fund's Realising Ambition programme

BACKGROUND

Respect specialises in helping frontline practitioners work effectively with perpetrators of domestic abuse. Between 2008 and 2011, the charity piloted a Young People's Toolkit, helping professionals intervene with young people who are abusive and violent in close relationships. But there was demand for a specific intervention tackling violence and abuse towards parents. "We wanted to do something more structured, working with the family as a unit," says development director Neil Blacklock.

Piloted in seven areas from 2012, Respect's Young People's Programme is now used by youth offending, family and domestic abuse services in North Yorkshire, Gateshead, Greater Manchester, Stockport, Rochdale, Calderdale, Leicester, Swindon, Margate and Wiltshire.

ACTION

Frontline staff get an initial four days' training by Respect, plus 12 two-hour "practice support" sessions over their first two years. Young participants are referred by schools, children's services, police, or parents themselves.

The programme consists of nine individual or group sessions with the young person, seven with the parent or carer and two family sessions, spread over around three months. The practitioner starts by bringing the young person and parent together to focus on what they respect and admire in each other, which they have "often lost sight of in all their difficulties", says Blacklock.

The young person's sessions involve helping them spot triggers for anger that could lead to abuse, understand the emotions and negative thought patterns driving their behaviour and learn strategies to regulate these such as "self-talk". Sessions with parents help build understanding of the factors influencing the young person's behaviour and how domestic violence skews family dynamics. They learn how to de-escalate conflict and rebuild boundaries and parental authority.

Early on the parent and young person come together to write a "family agreement". Each pledges to stop negative behaviours such as shouting or throwing things and start positive new ones. They agree a calming down and "time out" strategy and the consequences and rewards resulting from breaching or upholding these pledges.

In week seven, the young person records a video for the parent, explaining his or her behaviour and feelings and outlining how things could improve. This starts a restorative dialogue between both parties, building empathy, accountability and understanding. "We do this on video because it slows things down, so things get heard better," explains Blacklock.

Participants leave with the strategies they need to manage and resolve conflict. Gateshead youth offending team case manager Christine Rooney describes the programme's family agreement and video work as "key tools" in helping families move forward and make positive changes.

OUTCOME

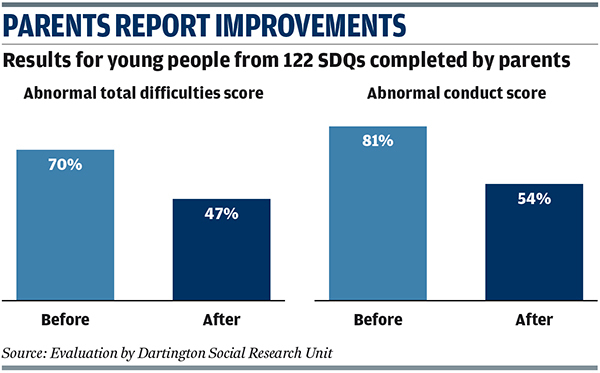

An evaluation by Dartington Social Research Unit - now Dartington Service Design Lab - in July 2016 shows the programme led to improvements as measured by strengths and difficulties questionnaires (SDQs) completed by both young people and adults.

A total of 212 SDQs completed by young people show 56 per cent improved their "total difficulties" score. The proportion with a "normal" score increased from 33 to 41 per cent while the proportion with an "abnormal" score decreased from 37 to 31 per cent.

Two thirds of young people - 67 per cent - improved their total difficulties score according to 122 SDQs completed by parents. Meanwhile the proportion with "normal" scores increased from 17 to 41 per cent and those with "abnormal" scores dropped from 70 to 47 per cent. In all, 66 per cent improved their "conduct difficulties" score with the proportion of "abnormal" scores falling from 81 to 54 per cent.

If you think your project is worthy of inclusion, email supporting data to derren.hayes@markallengroup.com