Behind the Inspection Ratings: Single assessment framework

Jo Stephenson

Tuesday, January 3, 2017

The single assessment framework was introduced in 2013 to bring together a number of separate inspections of children's social care. What do the judgments so far tell us about the standard of services?

More than three years on since the introduction of the single inspection framework (SIF), most local authorities have been through the process.

While the introduction of SIF has proved controversial with concerns over the complexity of children's services being summed up in a single word judgment and that the regime is overly harsh, directors of children's services (DCS) who have been through the process have acknowledged its rigour.

Gerald Meehan, former DCS turned chief executive at Cheshire West and Cheshire Council, describes it as "the greatest test I have ever had in 30 plus years" of working in the sector (see case study).

According to the database compiled by the Association of Directors of Children's Services (ADCS), 121 inspections have been carried out as of December 2016, with results published for 116.

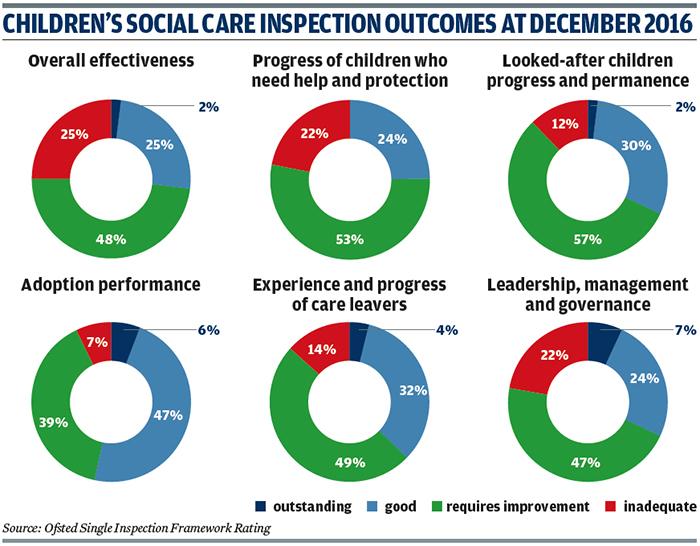

Of those, just two councils - Kensington and Chelsea, and Westminster - have achieved an overall rating of "outstanding". Both are part of an "exemplary" tri-borough partnership with Hammersmith & Fulham, which is one of 29 authorities - a quarter of those with published results - rated "good". Nearly half - 56 councils - are rated "requires improvement", while a quarter (29 councils) are rated "inadequate".

For many in the sector, such ratings are a blunt instrument.

The ADCS, Local Government Association and Solace (Society of Local Authority Chief Executives) called for a different approach, which would see the re-introduction of unannounced inspections of "front door" arrangements leading to wider multi-agency inspections if concerns or inadequacies were identified with a "narrative" overall judgment that draws out strengths as well as weaknesses.

"Single worded judgments cannot adequately capture the complexities and the interdependencies of agencies' actions to protect and care for children in a local area, and therefore cannot form a basis for improvement," argued a position statement from the three organisations.

In advice sent out to councils, Solace president and children's lead Mark Rogers argued the process was "inherently disposed to proving failure" and therefore urged managers to be pro-active as opposed to "passive recipients of inspection" by constantly checking inspectors drew on all the evidence available and insisting strategic leaders were "seen and seen early in the inspection schedule".

Under the SIF, children's services are judged on three criteria: children who need help and protection; children looked after and achieving permanence; and leadership, management and governance.

Two sub categories also assess adoption performance and experiences, and progress of care leavers.

If leadership is judged inadequate, councils can expect to be rated inadequate overall.

According to Ofsted's inspection framework, the DCS, lead member and senior management team must have a comprehensive knowledge of what is happening on the frontline to be effective.

They are expected to "drive continuous improvement" with established and systematic management oversight of practice, including scrutiny by senior managers, "demonstrably used to improve the quality of decisions and the provision of help to children and young people".

The published SIF results show eight councils are rated outstanding for leadership, management and governance, 28 are judged good, just under half are requires improvement and 26 councils are inadequate (see graphic).

A lack of management oversight was one of five common weaknesses in local authorities judged inadequate under SIF, in a summary published by Ofsted in November 2015 covering councils given the bottom rating in inspections between January and May of that year.

"Managers do not ensure that plans for children in care, child protection and children in need contain sufficient detailed information, are audited frequently enough and with sufficient scrutiny and identify and prioritise risk and take robust action to challenge when this is not the case," says the summary.

Leaders and managers were also too slow to respond to findings from previous inspection reports, inconsistent in supervision and feedback to social workers and had "not sufficiently reflected on or analysed poor practice".

Other common weaknesses included changes in leaders, managers and social workers leading to poor continuity for children and families, and issues around performance management.

On the flip-side, the inspection reports of the two councils rated outstanding overall show how strong leadership underpins high quality services.

At Westminster, "rigorous performance management means senior leaders are knowledgeable about the performance of services provided to children", says the authority's SIF report published last March.

Meanwhile, leadership and governance at Kensington and Chelsea is "of an extraordinarily high quality", says the council's inspection report also published in March, which describes the then tri-borough DCS Andrew Christie as "a pivotal figure".

The SIF cycle of inspections is to be completed by the end of 2017, with 31 councils still to be assessed. Ofsted is proposing to replace it with a lighter-touch system.

Whatever comes next, the SIF has been instrumental in raising expectations of standards in children's services.

Case study: ‘Obsessional' focus on needs of children

Cheshire West and Chester | Good overall | February 2016

Cheshire West and Chester has made huge progress since being judged "inadequate" for safeguarding by Ofsted in 2010.

In its SIF inspection carried out in November and December 2015, the authority's children's services were judged "good" overall, with "outstanding" ratings for adoption, and leadership, management and governance.

"This outstanding leadership has resulted in good-quality services that respond to the needs of children and families quickly and effectively," says the inspection report, published last February.

It has taken time and a lot of hard work to get to this point, says Gerald Meehan, who oversaw the changes as joint strategic director for children's services at Cheshire West and Chester and Halton Councils, and six months ago became chief executive at Cheshire West and Chester.

The starting point was an "almost obsessional" focus on the needs of children. Meanwhile, the shift required support and commitment from the whole council. "Without that commitment across the board, it is extremely difficult to raise the quality of children's services," stresses Meehan.

This has included a commitment to investing in early support and services such as education welfare and the area's successful Troubled Families initiative.

It has also meant investing in frontline staff and ensuring social workers receive quality supervision and the time and space to reflect on their practice.

Managers need to keep on top of workload, says Meehan although he admits this is easier said than done. "You can't expect staff to provide high-quality services if they have 35 to 40 cases - it is not possible without burnout," he says.

Introducing practice leaders to social work teams has helped boost support for new workers and ensure an ongoing drive to improve day-to-day practice.

Staff have training in "emotional resilience" and Meehan has also made a point of recognising and celebrating good practice.

"Staff do amazing things every day and it is important we notice that, otherwise senior leadership ends up being defined by complaints," he says.

The authority has seen fewer vacancies, less turnover and less sickness absence as a result.

Robust information systems are key, adds Meehan, and managers need to "know what is coming through the door" and then use that information to shape services.

So too is the support, scrutiny and challenge provided by the area's safeguarding and quality assurance unit, which includes the local safeguarding children board, child protection chairs, independent reviewing officers and participation services.

Social workers do not always get things right, and frontline staff and safeguarding unit colleagues may not always agree, despite having the same goals. What is needed is a "mature relationship" with a clear escalation process that is put into action when disagreements arise, says Meehan.

The authority's Ofsted report highlights the fact it "talks to young people and listens to them".

The council has two Children in Care Councils - one each for younger and older children. "They are involved in all policy decisions and every interview, including interviewing me for the chief executive role," says Meehan. "They have a loud voice and make a real difference. They were made up about our inspection result. I told them ‘you should feel proud because you made a significant contribution to it'."