Making the case for personalised learning

Charlotte Goddard

Thursday, January 2, 2020

Personalised learning approaches, often using the latest technology, improve the attainment of disadvantaged children, but critics are concerned it narrows the curriculum, finds Charlotte Goddard.

Use of artificial intelligenceto support children’s education may sound likea futuristic concept butit is happening now. Earlier this year the Departmentfor Education set up anAI Horizon Scanning Group to explore howAI might impact education policy and the potential benefits. One of the uses of AI in education is in developing personalised education systems through devices which learn about the individual needs of every student and provide education that meets those needs.

The definition of personalised learning varies depending on who is talking about it. “Part of the problem with the term ‘personalised learning’ is that it means different things to different people,” says Stephen Rollett, curriculum and inspection specialist at the Association of School and College Leaders.“If you take the basic notion to mean the needs of children should be met, there is little to disagree with. Good teaching depends on teachers monitoring the learning of pupils at an individual level and responding as required.”

The term can also refer to the idea each child should have individually tailored education, studying content that matches their interests and being taught using different work and resources. “This was a significant feature of education policy in the late 1990s and early 2000s,” says Rollett. Content and delivery may also be personalised based on a child’s progress or learning behaviour using software that customises the learning experience for students.

Advances in technology and genetics have pushed personalisation to the forefront of education research and practice. “Personalised education is having a revival right now,” says Sophie von Stumm, professor of psychology in education and director of the Hungry Mind Lab at the University of York. “There has been renewed interest in recent years, connected to increased public acceptance that genetic factors may play a role in how children respond to education. There is growing recognition that children are very different in their ability to learn and the educational system may want to recognise these differences and work with them.”

Until now, teachers have lacked the tools to tailor material in a highly personalised way, but technology is changing that. “It is difficult to find out how many students in UK schools are exposed to some form of personalised learning,” says Dr Sam Sellar, reader in education studies at Manchester Metropolitan University. “But reports from the educational technology sector show these sorts of technologies are growingin popularity.”

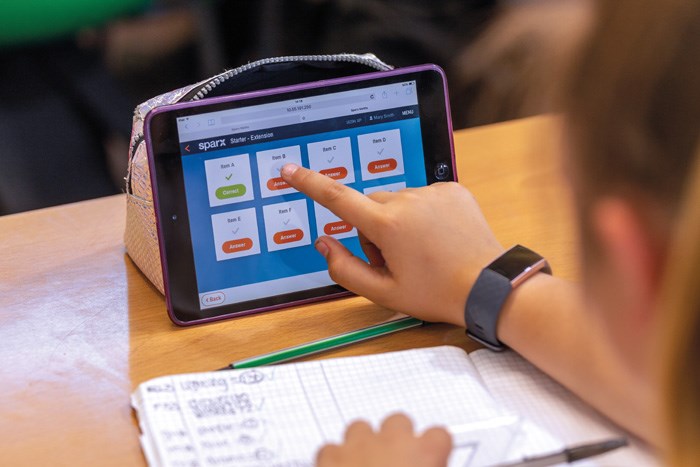

Tomasz Stefanski is head of data science at Sparx, which describes itself as a “socially focused learning technology company”. “Over the last one hundred years the way we’re taught at school has not changed,” he says. “The teacher is at the front of the class teaching the same thing to everyone, regardless of what children do or do not know. For a significant number the questions will be too easy and not engaging while many others won’t know the basics and are already lost.”

Sparx is working with around 1,400 primary and secondary schools to change the way maths is taught. In class, children use digital devices to complete work set by the teacher. “The teacher still teaches the whole class the same topic,” says Stefanski. “But as students answer questions they get to different places and the teacher can see that in real time. They might see a student already stuck on a basic question and can then offer support.”

Each child receives different homework, depending on performance. “Which concept did you learn and which did you struggle with? Is this topic appropriate or do we need to put that on hold and take you back to a previous topic – or is it too easy so we need to fast forward to a harder version?” says Stefanski. “This also improves their motivation – if you repeatedly ask someone a question they can’t answer it is not surprising they get worried.”

Teaching adaptation

An evaluation of 212 students using the Sparx maths product found they made 67 per cent more progress in year 7 and a further 63 per cent more progress in year 8 than the national average. St James’ School in Exeter has been using Sparx since 2011. “A really important insight is the ability to identify which questions students are finding challenging. This is often different from what I expect,” says Philippa Stevens, a maths teacher at the school. “Where the challenge is consistent for many students, I will revisit the topic in class and adapt how I teach it in future.”

Sparx’s own research suggests children eligible for the pupil premium at schools using its personalised learning system make 78 per cent more progress in maths than at schools that don’t. Almost a third – 32 per cent – of pupils at Cranbrook Education Campus in Exeter, which takes in students aged two to 16, are eligible for the pupil premium. The school, part of the Ted Wragg Multi-Academy Trust, allocates some of this funding to buying in personalised learning systems, including Sparx. As well as improving results and confidence in maths for students, the school says Sparx is saving each teacher around two hours a week on admin, planning, and marking.

In a trial of 16 schools using the Sparx system, Cranbrook year 7 and 8 pupils had the highest rate of progress in year 7 and 8 maths. Results showed disadvantaged children were making the same progress as more advantaged peers.

Personalisation is not just about delivering different content based on attainment, says Iolanda Leite, assistant professor at the Department of Robotics, Perception and Learning at Sweden’s Royal Institute of Technology. It can also adapt to children’s behaviour (see box, p27). “For example, we can use AI to track the child’s posture, which givesa clear indication of whether they are engagedor not, and intervene accordingly,” she says. Teachers do this all the time, so is it worth all this effort trying to make a robot do the same thing? “School is not always one teacher delivering the same content to 30 kids,” says Leite. “There is often small group work and different activities. Technology is not going to replace teachers but the teacher can’t clone themself to be in all the groups at once.”

The personalised approach is particularly effective for children from more disadvantaged backgrounds who may suffer from a lack of support at home which affects their motivation, says Stefanski. “Students from a disadvantaged background or those who really struggle with maths say because their work is tailored to ability they suddenly start enjoying it again.”

Educational technologist Amy Ogan, professor of learning science at Carnegie Mellon University in the US, agrees personalised learning is particularly beneficial for disadvantaged pupils. “Students at the higher end of attainment often have the motivation and skillset to learn on their own, but lower achieving students do not,” she says. “The intention is to use technology to free the teacher to spend more time with individual students, so students at the lower end get more personalised attention.”

Following children’s preferences

Others, however, think personalisation can be harmful for disadvantaged children. Tim Oates, group director of assessment, research and development at Cambridge Assessment believes following a child’s interests can increase the gap in attainment between disadvantaged children and more advantaged peers. “By the time children hit school they will have already developed certain preferences and it may be good or very bad to follow those preferences,” he says. Children might have already decided they are no good at maths, for example. “It can lead to an incoherent or narrowed experience of the curriculum because key content may be missed or taught out of sequence,” agrees Rollett.

Clare Walker* believes personalised learning was not the right approach for her son Oliver*, 16. Until July this year, Oliver, who has autistic spectrum disorder, attended a mainstream comprehensive where every child was given an iPad. “With the iPads came the idea they could independently go with their own interests and ideas about things,” she says. “The school wanted to get away from being teacher-led and become student-led.” Children were given broad information on a topic and expected to research what interested them. “For those children who are creative, that’s great, but for Oliver who needs specific instructions for things and struggles with abstract thought, it did not work out, and the school seemed unable to address that,” explains Walker.

A system called My Learning Choice allowed struggling children to book a catch-up lesson. “The problem with that was they would have to miss another lesson, say English, to get a catch-up in maths,” says Walker. “Oliver couldn’t access that because it freaked him out not to be in the lesson he was timetabled to be in. Also the onus was very much on the child to know when they were struggling.”

Walker believes the school’s approach contributed to Oliver’s poor results at GCSE. He was predicted 4s and 5s – standard and strong passes – but his highest was a 3 – equivalent to a D. “He has to re-sit his maths and English at the college he is at now,” says Walker.

The way personalised learning is being driven by big technology companies is causing some concern. “The process of developing the curriculum and agreeing what should be taught should be inclusive and democratic but the more this technology is brought into schools the less we’ll see of that consultation with teachers and other stakeholders,” says Dr Sellar.

Personalised education systems generate a huge amount of data on each individual student. Who owns that data, and what will it be used for? Technology may also suffer from in-built bias. Personalised learning systems built using data from one set of students may be less able to predict the needs of another demographic group.

Genetic profiles

Some researchers envisage a time when a child’s genome will be analysed to provide a completely individualised learning programme. In October 2019, Kings College London’s Professor Robert Plomin told a head teachers’ conference UK schools would soon be able to tailor the education they provide based on information about pupils’ genetic profiles. But while von Stumm’s research is identifying the role of genetics in children’s ability to learn, she does not believe personalisation is currently the answer. “Children differ in their ability to learn,” she says. “The question is what do you do with this piece of information? Would I recommend using DNA to identify children with learning difficulties? Not currently. We have good diagnostic tests we can use for that. However, these tests only work when problems are already evident. The potential advantage of using DNA would be to predict problems early, before they occur.”

Oates believes the best personalisation does not look like personalisation at all. “You can see something that looks like rote learning, with the children all saying the same things, but it is profoundly individual,” he says. “The teacher is asking penetrating questions to every child in the group, the whole group is sharing answers. At the end the teacher holds back four or five children they are worried about and those children get support in the next 24 hours to make sure they’re not falling behind. That is a form of personalisation I support.”

Teachers – and policymakers – need to look at the evidence behind systems before signing up to them. “AI and personalisation are the buzzwords you hear about everything now,” says Stefanski. “Our key message is not ‘our product uses AI and is therefore great’, our key message is it is ultimately there for the learner, and teachers are still in control.”

*Name changed

WHAT THE RESEARCH SAYS

Potential limitations

The study: Personalised Learning and the Digital Privatisation of Curriculum and Teaching, Faith Boninger, Alex Molnar, and Christopher Saldaña, National Education Policy Centre, University of Colorado, April 2019

What was done: An analysis of the scope and limitations of personalised learning in the US.

Findings: Because personalised learning in the US is driven by technology, it tends to limit learning to subjects that can be taught in a logical way and those easy to assess with right or wrong answers. The authors suggest this does not allow children to follow their own interests and raise concerns about handing over decisions about teaching and the curriculum to faceless programmers.

Implications for practice: The authors urge caution over the widespread adoption of personalised learning until there are robust systems to review the benefits and ensure accountability and independent oversight, including when it comes to use of personal data.

Impact on achievement

The study: How Does Personalised Learning Affect Student Achievement? John Pane and others, Rand Corporation, December 2017

What was done: Researchers analysed maths and reading scores for around 5,500 students in US schools that took a personalised learning approach and those that did not.

The findings: Children in the schools that used personalised learning started out significantly below the national average in maths and reading but gained ground over two years with most progress made in the second year. They were above national average at the end of the second year with improvements made by low and high achievers.

Implications for practice: The findings suggest personalised learning can improve students’ achievement regardless of their starting point. However, the benefits take time to emerge and there is a lack of evidence on the most effective approaches.

Robots in UK primary schools

The study: Robot Education Peers in a Situated Primary School Study: Personalisation Promotes Child Learning, Paul Baxter and others, PLOS One, May 2017

What was done: Two robots were placed in two UK primary school classrooms for two weeks. One personalised its behaviour depending on the behaviour of the child and one did not. Children were taught a new and a familiar subject.

The findings: The results suggest children learning the new subject learned more from the personalised robot than the standard one. There was no difference in learning the familiar subject. Children were more accepting of the personalised robot.

Implications for practice: The robots caused some disruption at first but children enjoyed using them. Overall the researchers concluded personalised robots were a “positive influence” on children’s learning but more research was needed on how best to maximise impact.

ROBOTS HELP PERSONALISE CHILDREN’S LEARNING

In a classroom in Sweden, a group of primary school children are playing a game with a robot. Some have recently arrived in Sweden, others were born there. “The newly-arrived children tend to go into a different classroom where they don’t interact with kids who have been here a while,” says Iolanda Leite, assistant professor at the Department of Robotics, Perception and Learning at Sweden’s Royal Institute of Technology. “We are working with teachers to design activities that provide more interactions between newly arrived children and Swedish children. If they have a task they can do together they will start speaking the language more and integrate earlier.”

Leite’s research project is looking at how robots can learn from a child’s behaviour, and use that information to personalise their interaction with that child. “We use robots to try to influence certain behaviours during collaborative tasks in the classroom, particularly looking at making sure each child has an equal amount of participation in the group,” says Leite.

The task involves children moving coloured cubes around a board. When they have created the right pattern, they can make a tune. The robot tracks each child’s movements, and encourages them to interact with each other by placing cubes in other children’s zones. “If they tend to stay in their own zone, the robot prompts them to explore the other kids’ areas of board,” explains Leite. “The robot turns to the child when they are exhibiting certain behaviours – maybe they are not speaking much. The robot will turn and prompt the child to pick one of his or her cubes and place it in another kid’s area.”