Fall in YOI staff linked to restraint increase

Fiona Simpson

Tuesday, February 25, 2020

Former chief inspector of prisons Nick Hardwick calls for workforce improvements to tackle rising restraint use in the secure estate.

![Nick Hardwick: “We need to see people equipped with skills to navigate complex and hostile situations, who want to de-escalate [these] without the use of violence.” Picture: Nathan Clarke](/media/202841/nick-hardwick-by-nathan-clarke.jpg?&width=780&quality=60)

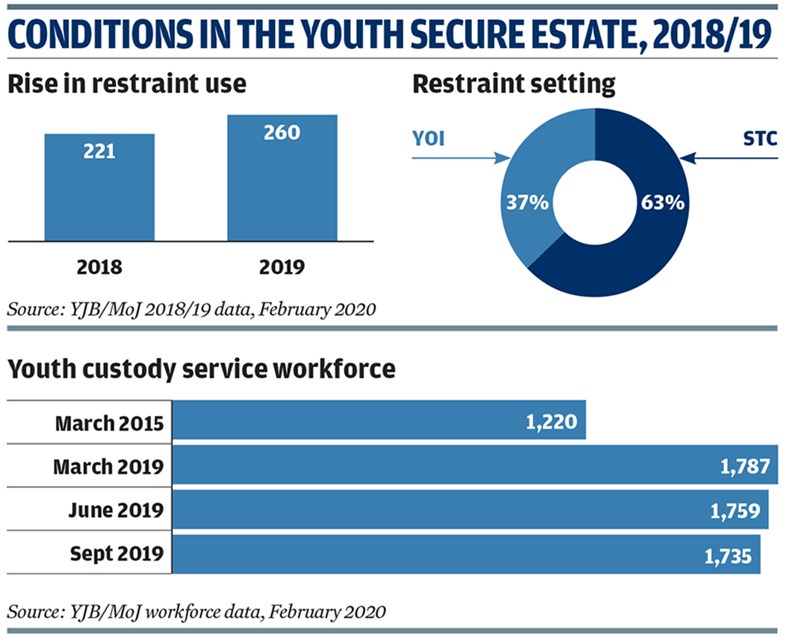

Latest official figures show the use of restraint in youth custody is at a five-year high, while the number of full-time staff employed by the Youth Custody Service is at its lowest level for two years.

Campaigners have called the figures a “child protection scandal”, and now former chief inspector of prisons Nick Hardwick has warned that the trends in the two sets of figures could be linked.

A shortage of prison officers, long hours for those working in young offender institutions (YOI) and lack of training has combined with a rising group of young people with unmet complex needs to create the circumstances for rising restraint use, he says.

Between April 2018 and March 2019, restraint incidents in YOIs and secure training centres (STC) increased by nearly 18 per cent.

Meanwhile, between March and September 2019, full-time youth custody staff fell nearly three per cent.

Abuse allegations

Across the six local authorities with youth custody establishments in their area, there were a total of 557 allegations of abuse and neglect between 2016 and 2019, according to Freedom of Information request results published by charity Article 39.

At Oakhill STC, in Milton Keynes, 52 of 98 allegations of abuse and neglect by staff were found to be substantiated.

Medway STC, in Kent, was rated as “inadequate” by Ofsted in its last inspection, while Oakhill and Rainsbrook, in Warwickshire, were both rated as “requires improvement”.

Hardwick says a decline in workforce numbers and a lack of relevant training for prison officers can contribute to high tension in youth custody.

Training is too heavily focused on techniques such as pain compliance with little weight given to dealing with the complex needs of young people, including mental health issues, past trauma and special educational needs and disabilities, he adds.

“You have staff who are not equipped with training to deal with these young people with very complex needs, who are paid very little and work in tough, often not very nice environments.

“I can sympathise if, at the end of a long shift, there is a young person refusing to go back to his or her cell, tensions are escalating and you have people equipped with the knowledge of pain compliance techniques – as long as these are deemed acceptable in some circumstances, they are going to be used,” Hardwick says.

Echoing calls made across the sector for better training for youth custody staff, he adds: “We need to see people equipped with the skills to navigate complex and often hostile situations, who want to be working with these young people to de-escalate the situations without the use of violence.”

Over the past decade, the number of first-time entrants to youth custody has decreased by 83 per cent, with recent figures published by the Youth Justice Board and Ministry of Justice showing a decline of 18 per cent over the past recorded year alone.

Questions over facilities

Hardwick puts the decline in first time entrants, in part, down to a move away from handing first-time offenders custodial sentences, but he warns this risks leaving more serious offenders in fewer facilities.

“What we have left is a handful of the most vulnerable young people, often with the most complex issues, who have committed the most serious, often violent crimes put together in these underperforming facilities,” Hardwick says.

“Prison is not the place for vulnerable young people with often complex needs.

“One problem with youth custody facilities is that with a decline [in the number of young people in youth custody], the facilities are too big and too imposing.

“Young inmates can be left feeling isolated and the buildings don’t lend themselves well to becoming environments that can foster rehabilitation.”

However, Hardwick says the closure of too many sites could lead to issues in finding suitable facilities for young people caught up in county lines drug dealing.

“You have situations where a young person has been told if they are placed in this facility or that facility, they will be in danger from rival gang members or acquaintances of rival gang members,” he says.

“This is something that does need to be looked at to keep young people out of danger and to avoid fights breaking out in custody.”

Secure schools

In 2016, in response to Charlie Taylor’s review of the youth justice system, the government announced plans to replace youth custody settings with secure schools – the first of which is due to open on the site of Medway Secure Training Centre in 2021 (see box).

“The danger we have here is that we have the same establishments with a slight focus on education,” Hardwick says.

Instead, he calls for more focus to go on preparing young people for release, with local authorities, probation and police involved in planning the transition into life outside of custody.

“These are often young people who are coming out of custody with nowhere to go, no way of getting income and no support in establishing these things for themselves,” he adds.

Hardwick – who is about to step down as chair of trustees for north London youth centre New Horizons after a decade – says voluntary organisations also have a part to play in helping young people released from custody to find their feet.

However, having a consistent social worker and probation officer would make communication between agencies easier and allow young people to feel more comfortable in this transition, he says. “What is really key is listening to these children and young people – we have seen here [at New Horizons] that they have a voice and they want to have a say in their own future.”

REVIEW EXPECTATIONS

Charlie Taylor, chair of the Youth Justice Board, is set to publish a review of the use of restraint in youth custody imminently.

Hardwick says it will be “interesting to see what comes out of the long-awaited review”.

“The use of pain compliance techniques in custody is not new, it’s something we’ve been doing since Victorian times and is a highly outdated way of dealing with people in custody, most certainly children and young people,” he adds.

A Youth Custody Service spokesperson said in January that the review was being “carefully considered” before a response is published.