Evolution of youth work courses

Derren Hayes

Thursday, May 4, 2017

Amid closures of some youth work degrees, universities are adapting how they train future practitioners

The closure of one of the longest-established youth and community work degree courses as a result of falling student numbers has raised fears that cuts to council youth work jobs and services in recent years is making the career less attractive.

Last month, Manchester Metropolitan University (MMU) announced it will no longer accept new entrants for its youth and community work degree, saying a slump in job prospects for youth workers due to the effects of austerity in public sector spending was largely behind the decision.

Latest data from local authority section 251 returns shows council spending on youth services fell from £815m in 2012/13 to £500m in 2015/16. Shrinking budgets have seen local authorities cut their own services and the amount contracted to voluntary sector providers.

Despite the gloomy financial picture, youth work educators have defended the health of university courses, saying the sector is adapting degrees to ensure professional qualifications remain relevant and valued.

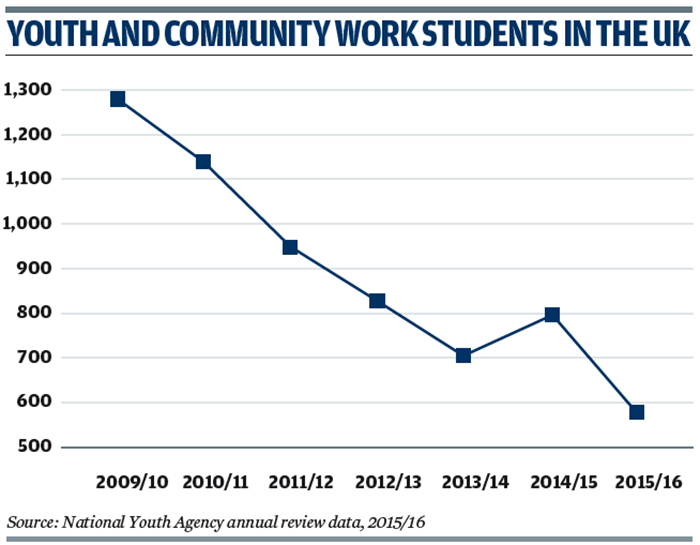

However, latest figures from the National Youth Agency (NYA) show the number of youth and community work students on undergraduate and postgraduate courses fell from 793 in 2014/15 to 572 in 2015/16, a drop of 28 per cent and less than half that in 2009/10 (see graphic).

In contrast, the number of youth work degree courses run by higher education institutions (HEI) increased from 16 in 2007 to 38 in 2010. It has fallen steadily since then, dropping 10 per cent last year to a total of 27 in 2015/16.

However, the NYA says the figures are incomplete and still need to be validated.

An NYA spokeswoman says: "NYA's annual monitoring survey canvasses a return from each validated youth work programme and provides a definitive overview of professional youth work qualifications.

"We make the data available each year in July once it has been reviewed and approved by the education and training standards committee.

"The 2015/16 data has not yet been assembled. Until then any figures relating to professional youth work qualifications should be treated as incomplete."

In addition, a recent snapshot survey of 35 English HEIs offering approved youth and community work degree and postgraduate programmes found that 10 of these courses had either "run out" - closed to new entrants - or were "at risk of run out".

The survey by TAG: The Professional Association of Lecturers in Youth and Community Work also found that the average number of students on courses was just 19.

Fewer courses

TAG national officer Paul Fenton says the average number of students masks huge variation between courses, with the fewest being eight and the most 47.

"Some courses are quite healthy, while others are unsustainable," he says. "I would expect to see fewer courses in the next few years - maybe half the 35 currently in England."

Fenton admits government cuts have made some students more nervous about choosing youth work, but that this is not the only factor. He says other issues include fewer young people having experience of youth work in their own life and so not considering it as a profession; and restrictions on the maximum number of students per lecturer mean youth work courses are not as financially attractive for HEIs.

He adds that concerns over employment prospects "are a perception that is not necessarily matched by the reality". "Graduates from youth and community work courses go into jobs more easily because they get transferable skills, they are just not going into local authorities as much."

NYA data shows that in 2015, 23 per cent of youth workers were employed by councils and 44 per cent by voluntary sector organisations. While the numbers working in authorities has remained fairly static, those employed by the voluntary sector have risen more than a third.

Fenton says youth work skills are also being increasingly utilised in non-youth work roles, indicating the profession is having a "broader reach".

New courses are emerging to reflect this change in professional roles and practice. MMU, which has offered professional youth work qualifications for more than 35 years, plans to establish a community education three-year degree course in 2018.

Meanwhile, YMCA George Williams College is developing new degree programmes, including social pedagogy, which go beyond "traditional" youth work.

Simon Frost, head of higher education programmes at the college, says: "There is still a need for youth and community work as a distinct area of practice - however, we are seeing an increase in youth and community worker students taking on a broader range of roles across the children, young people and families sector.

"The college believes the principles of youth and community work still have currency, but also that it has much to offer beyond its traditional parameters."

Repositioning degrees

Other HEIs have repositioned youth and community work degrees to better reflect the changes in the youth work sector.

For example, the University of Derby course has renamed its course Working with Young People and Communities. Using youth work skills in a broader context means Derby students now undertake placements that were traditionally available only to those studying social work, education or health courses.

It has also developed inter-professional learning opportunities that see students discuss case study scenarios alongside trainee nurses, occupational therapists, midwives, counsellors and social workers.

In a letter to CYP Now, the university says: "Youth and community workers have never worked in isolation; they encourage change, challenge inequalities and work alongside other professionals.

"We promote the view in other professional areas that youth work is an individual professional skill-set that the practitioner takes with them into any scenario."

However, Fenton says the "market adjustment" needs to be seen in the context of youth work courses more than doubling between 2007 and 2010.