Deprivation is key factor affecting spending on children's services

Derren Hayes

Tuesday, June 26, 2018

LGA analysis shows demographic and social issues linked to deprivation account for half the variation in spending on children's services. Sector leaders say it reinforces calls for government to increase funding.

Ministers have consistently rebuffed calls for more money for children's services, arguing that many councils are failing to use existing resources efficiently. They cite the fact that an authority in one part of the country can spend half of that in another part of the country to achieve the same outcomes for children - as measured by Ofsted ratings.

The lack of in-depth analysis of the factors influencing children's services spending has meant local government leaders have struggled to explain the reasons for the variation. However, the Local Government Association (LGA) hopes new research, undertaken by consultants Newton Europe over the past six months, will provide the evidence the government needs to reconsider.

The four key factors influencing the variation in spend between councils are summarised here, with reactions from sector leaders.

Deprivation

The research looked at national economic, demographic and geographic data and identified deprivation as having the strongest influence on spending variation.

It found that councils with higher average IDACI scores - the index that measures child deprivation - spend more per child than those in less deprived areas.

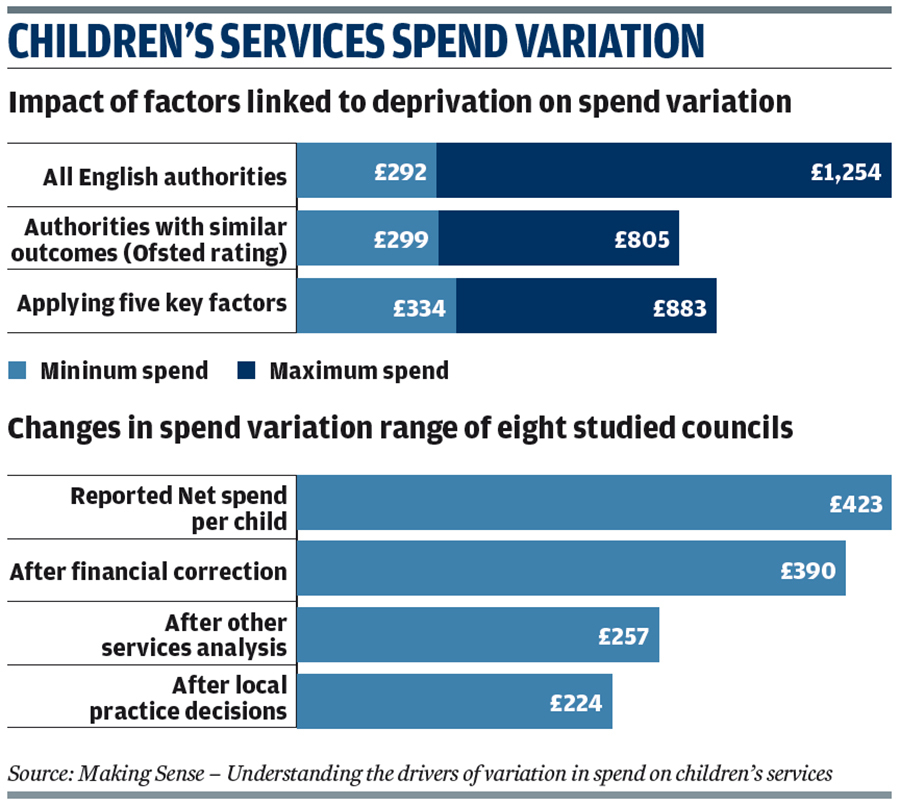

The variation in spend per child across all 152 English local authorities was £292 to £1,254 (see graphic), a range of £962. However, this variation in spending reduces to £299 to £805 when comparing councils with similar Ofsted outcomes. Newton concludes that deprivation alone accounts for 31 per cent of the variation in spending.

When four other key socio-economic factors linked to deprivation are factored in - child population size, disposable household income, unemployment and crime levels - the variation in spending amounts to 50.1 per cent. Once this is taken into account, the variation in spend per child is £334 to £883, a range of £549.

Financial reporting

An analysis of the practices and decision making within eight local authorities was undertaken. They were selected based on having similar levels of deprivation and achieving similar outcomes. The variation in per child spend by these was £382 to £805, a range of £423 (see graphic).

Revenue outturn data was probed to identify "discrepancies" in reporting practice and compare spending on a like-for-like basis.

Of the eight councils analysed, five over-reported and three under-reported spending. This was due mainly to different interpretations of guidance and financial reporting errors.

Four key factors contributed to this: how much of corporate overheads were allocated to children's services; the number of unaccompanied asylum-seeking children being supported; whether grant funding was treated as income or gross spending; and coding inaccuracies.

Once these were factored in, variation in per child spend was £407 to £797, a range of £390.

Local practice

The study analysed how individual councils' practices and decision making can influence children's services spending. Case review workshops analysed how best outcomes for children were achieved, the financial implications and its impact on spend variation.

Four factors are identified as the key drivers of variation in spend: avoiding a child being taken into care; preventing drift in casework; ensuring the best care setting for a child; and placing children in the best level of support following assessment.

Other services

Rising demand for transport services for special educational needs and disabilities pupils was identified by councils as a major unfunded pressure that is causing them to scale back in other areas.

The study did not assess how effective greater investment in early help services is at reducing spend for more intensive interventions. However, it noted that "councils spending more on these services tended to do so primarily as a result of political or strategic commitment" to it.

Differences in children's services practice accounted for 13 per cent of spend variation.

When local practice and other services factors were applied to the eight councils, the variation in their per child spend was £236 to £460, a range of £224.

NOTIONS OF INEFFICIENCY AND POOR PRACTICE ‘DISPROVED'

By Richard Watts, chair, LGA children and young people board

We are regularly quoted statistics that show some children's services departments spending considerably more than others, with the clear suggestion that higher spenders should be able to reduce their budgets to match those of lower spending areas elsewhere.

The research focuses on understanding these differences and shows such arguments are misguided and short sighted, explaining for the first time why variation is an inevitable result of the specific circumstances facing individual councils.

While the research demonstrates that the majority of spend variation is due to wider economic or geographic circumstances largely outside the control of children's services, it is frustrating that inconsistent financial returns continue to hinder efforts to easily compare the cost of delivering services in different areas. This report will help councils to identify the changes required to address this issue locally.

This research was squarely focused on the question of why council spend on children's services varies across the country, and comprehensively disproves the notion that this is simply a result of inefficiency or poor practice. But we are now left facing the bigger question of where we go from here.

Demand for children's services continues to increase, yet we have no long-term strategy to address this growing need and no sustainable funding solution to enable councils to meet it.

‘SHORTSIGHTED' GOVERNMENT FUNDING POLICY EXPOSED

By Stuart Gallimore, president, Association of Directors of Children's Services

The report illustrates the pressure councils are experiencing in terms of rising levels of need for help and support against a backdrop of a 49 per cent reduction in funding since 2010.

Protecting children and young people from significant harm has been understandably prioritised, but this has come at a cost - non-statutory prevention and early intervention services, such as children's centres, have been eroded and are now seriously at risk.

The government's current approach to funding children's services is incredibly shortsighted and I worry about the human and financial costs we are storing up for the future.

The report demonstrates the complex reality of delivering children's services and the multitude of factors influencing spend, from the contribution of partner agencies, how developed early help arrangements are, the size of the child population and different financial reporting methods.

The report shows the impact of levels of poverty and deprivation, and that variation in spend is due to a variety of factors that are largely out of the control of individual local authorities, busting the myth that there is enough money in the system. There is not.

The government urgently needs to commit to a preventative approach to improving children's outcomes and the development of a cross-departmental child poverty reduction strategy.

CENTRAL GOVERNMENT MUST TACKLE CAUSES OF DEPRIVATION

By Ray Jones, emeritus professor of social work, Kingston and St George's University of London

There is no doubt about the demands created for children's services from deprivation. Tackling deprivation is a good thing in its own right, but we now know that there is a significant impact on the workloads for children's services.

There should be no excuses or rationale for ministers to kick this into the long grass and say they need more evidence on the link between poverty and demand for services. The government needs to recognise the impact of deprivation on variation in spending. Tackling this may be out of the control of local authorities, but central government can make changes to the social security system that can address it. These are political choices.

There will always be differences in how authorities categorise spending as requirements are unclear. It's important for authorities to work with other councils with similar profiles through benchmarking clubs so they can compare approaches and come to a sensible way forward. It's about understanding what the data says about children's needs and how best to meet these.

There are also differences in practice, particularly in spending on early help. Compared to the impact of deprivation, these are fairly marginal, but councils should still be looking at data sets to see if they can learn from the approaches of others.

EARLY HELP INVESTMENT CAN CLOSE VARIATION IN SPENDING

By Sam Royston, director of policy and research, The Children's Society

The findings show the variation in spending on children's services is not principally the result of poor money management by councils, but instead geographical and social factors locally.

Alongside raising the overall amount of funding available, we need to shift spending towards early intervention - that is difficult for local authorities to do because their budgets are so restricted. Reductions in local government funding has translated to reduced investment in early help services. As a result, best practice approaches are increasingly unavailable to authorities because they have to put the majority of their money into delivering statutory services.

The government needs to reverse funding reductions for children's services and target more spending at children before they enter the care system. In addition, they need to target funding specifically at early intervention services.

The report finds that variations in children's services spending are dependent on deprivation. Another factor that could have increased the variation in spending is the reduction in financial support to families - such as cuts to housing benefit and the welfare cap - and the wider increase in the cost of living.

We are seeing the highest levels of spending in the most deprived councils, while the gap between the most and least deprived communities is growing.