Character Education: Policy context

Derren Hayes

Tuesday, October 29, 2019

At the recent Conservative annual conference, Culture Secretary Nicky Morgan reiterated her party's commitment to a wide-ranging character education agenda.

She said: "If we wish to use all the great talent in our country it is vital that we offer opportunities and the chance to build character and resilience to all."

Morgan has been an advocate of character education since her time as Education Secretary from 2014-16. She commissioned ground-breaking research to test what character education programmes worked best in schools and launched a £3.5m character grant programme that she said would make the UK a global leader in teaching character and resilience. The scheme was scrapped in 2017 by Morgan's immediate successor Justine Greening. However, Greening's successor Damian Hinds shared Morgan's enthusiasm for the agenda, to the extent that he established an advisory board for character education and set out five foundations for building character.

In July, Hinds was replaced by Gavin Williamson as Education Secretary, who so far has had little to say on the character agenda (see NCB expert view, below). However, the investment of £634m by the government up to 2017/18 on the National Citizen Service suggests character education is still very much on the agenda.

What is character education?

The "character education agenda" gained momentum in the 2010-15 coalition government and was linked to a drive by policymakers to set out the desirable traits that British children should have to become good citizens. In a new essay for the Institute of Public Policy Research (IPPR), Emma Worley, co-founder of the Philosophy Foundation, says that character education has always been central to schooling.

"From school mottos and assemblies, to lessons in grit and resilience…through their schooling, children learn how to behave and so develop character attributes that will stay with them as they grow older," she writes.

In his essay to the IPPR collection, Peter Hyman, executive head teacher at School 21 and former adviser to Tony Blair, explains how fundamental character education is to the success of his school. He writes: "We believe in developing a strong sense of wellbeing, an inner strength and a self-control, the ability to bounce back from setbacks and transcend often fragile and complicated lives. We do this through coaching, studying rich literature, giving pupils a range of experiences that help shape their characters and personalities."

Research suggests many school leaders share Hyman's view of character education. A 2017 survey by NatCen Social Research and the National Children's Bureau for the Department for Education found that 97 per cent of schools sought to promote desirable character traits among pupils in order to help them become good citizens, with 84 per cent also saying that it improved academic attainment.

The survey defined character education as any activity that aimed to develop desirable character traits in students, including tolerance, motivation, resilience, confidence, community spirit, honesty or conscientiousness.

Research in 2015 by the Jubilee Centre at the University of Birmingham, found 80 per cent of primaries and 54 per cent of secondaries employ a whole-school approach to character building, with 59 per cent placing a high priority on moral teaching (see research evidence). Morgan's now defunct character grants promoted these and other traits including perseverance, grit, optimism, integrity and dignity.

THE GOVERNMENT'S FIVE FOUNDATIONS FOR BUILDING CHARACTER IN CHILDREN AND YOUNG PEOPLE

- Sport

Includes competitive sport and activities such as running, martial arts, swimming and purposeful recreational activities, such as rock climbing, hiking, yoga or learning to ride a bike. - Creativity

Involves all creative activities from coding, arts and crafts, writing, graphic design, film making and music composition. - Performing

Activities could include dance, theatre and drama, musical performance, choir, debating or public speaking. - Volunteering & Membership

Brings together teams for practical action in the service of others or groups, such as volunteering, litter-picking, fundraising, any structured youth programmes or uniformed groups. - World of work

Practical experience of the world of work, work experience or entrepreneurship. For primary age children, this may involve opportunities to meet role models from different jobs.

In his speech on character and resilience earlier this year, Hinds attempted to build on these traits by setting out five foundations for building character. These cover a number of key areas - sport, creativity, performing, volunteering and membership, and the world of work (see above). Hinds said that these activities are a crucial part of a child's development and will teach them the qualities that cannot solely be learned in the classroom.

"This is not about a DfE plan for building character," he said. "It has to be about schools learning from other schools, business pitching in when it can, community groups speaking up and inviting schools in. It's about individual adults volunteering. All of us need to work together using the wide range of resources and experts that there are out there."

The view that character education goes beyond the school gates has been embraced by policymakers over recent years. In addition to the development of NCS, funding has been given to uniformed youth groups to expand their reach. Organisations like the Scouts and Sea Cadets have opened groups in disadvantaged areas (see practice example).

The expansion of uniformed youth groups is underpinned by a belief that the ethos and activities of these organisations can play a part in teaching young people positive character traits. This was recognised in the 2014 all-party parliamentary group on social mobility manifesto for character and resilience, which called for more focus on extra-curricular and non-formal education in helping young people realise their potential.

It is not just uniformed youth groups that provide character development opportunities. A range of youth groups and volunteer-based programmes offer access to activities that build positive character traits. This however can be difficult for youth organisations to define, according to A Way Forward for Character Development, a white paper written by education consultancy PDP.

The paper sets out a model for service providers and commissioners to use when developing character development interventions (see expert view, below), which is underpinned by the idea that the character agenda is about helping all young people to make the most of their abilities rather than it be seen as addressing a deficit in their make-up.

Character in schools

Most schools use a variety of methods to build character among the pupils, from formal character education lessons to voluntary activities outside the classroom.

Almost all schools surveyed in the NatCen/NCB research reported using a school mission statement or set of core values to develop character traits among students.

When it came to regular activities, nearly all schools reported delivering character education through assemblies, and around half focussed on the development of character traits in registration or tutor periods. Nine out of 10 schools said they had elements of character development within subjects, while 41 per cent had dedicated character education lessons. Among schools using subject lessons to develop character traits, PSHE (personal, social, health and economic) education or citizenship lessons were the most commonly reported used to develop character traits.

Meanwhile, just three per cent of schools reported using no extra-curricular activities to promote the development of character traits among their pupils. The most popular were:

- Sports and/or performance arts clubs (91 per cent)

- Outward bound activities (72 per cent)

- Hobby clubs (71 per cent)

- Subject learning clubs (60 per cent)

- Role model sessions (47 per cent)

Another common measure to develop character traits used by 44 per cent of schools was volunteering and social action. This was a particularly popular approach used by maintained secondary schools. For example, Swavesey Village College in Cambridgeshire has developed a programme of pledges built around volunteering that all students are expected to participate in throughout their time there (see practice example). According to school leaders, the approach sees students firstly participating in volunteering activities before moving on to develop and lead their own projects.

Such volunteering programmes are most common in secondary schools, although the research found that primaries were equally committed to character education. For example, more primary schools offered character education training to all staff than secondaries, and were just as likely to have a dedicated member of staff leading on character development. Staff commitment and a shared ethos was highlighted by primary school leaders as the most effective method for developing positive character traits in pupils. One way that schools are developing this is to bring in outside organisations to help deliver character education lessons. One such organisation is Commando Joe's, which delivers resilience building programmes by former military personnel in primary and secondary schools, as well as some early years settings (see practice example).

While most character education programmes are whole-school in nature, some interventions are targeted at pupils struggling with attainment or behaviour problems. The APPG on social mobility highlighted the potential that character and resilience programmes could have for re-engaging the most disengaged 16- and 17-year olds back into learning. Charity The Challenge recently piloted a version of its HeadStart programme with 90 students aged 14-18 in three London schools identified as being at risk of becoming not in education, employment or training (Neet). Activities on the 16-week programme are geared towards building resilience as well as developing employability skills (see practice example).

Government vision

In addition to setting out his "five foundations for building character", Hinds announced a range of policy measures to further develop the character agenda. These included plans for an audit of out-of-school activities to identify areas that need more provision; relaunching the DfE's Character Awards to recognise innovative programmes; and creation of an advisory group led by PSHE expert Ian Bauckham to develop a new framework to help teachers and school leaders identify the best activities for building pupils' character. The framework will include benchmarks for character education against which schools will be required to assess themselves - a call for evidence closed in July, with the advisory group due to publish its recommendations in the autumn.

Some changes have already taken effect. Ofsted's recently introduced Education Inspection Framework places greater emphasis on character education and that pupils have access to extra-curricular activities.

A recent review of extra-curricular activities by the Social Mobility Commission found a strong link between pupils developing soft skills - such as team work, communication and problem solving - and success in the workplace. The review found half of all job vacancies were related to these skills shortages, and recommended increased involvement of the voluntary sector in widening opportunities for young people.

Other policy initiatives supporting the character agenda include the #iwill fund, a joint government and National Lottery Community Fund programme, which has already enabled more than 300,000 young people to participate in youth social action opportunities.

The flagship NCS scheme has seen more than 500,000 16- and 17-year-olds participate in social action projects in their local communities, often being linked into school-based character development schemes. Also, the Education Endowment Foundation has been funded to trial 15 projects with a focus on character and essential life skills - one of which is Commando Joe's - with a view to promoting evidence-based interventions.

When announcing his future vision, Hinds said young people today are "compassionate, civic minded and hard working", adding that they have far more "confidence and ambition" than his generation.

"What I want is for us to reach higher and wider, to improve further…to make sure these opportunities are available for everyone and that we value fully the development of character and resilience in all young people."

EXPERT VIEW

WHERE NEXT FOR CHARACTER EDUCATION?

By Matthew Dodd, head of policy and public affairs, National Children's Bureau

Character education was an area of policy in which the previous Education Secretary, Damian Hinds, had a clear and long-standing personal interest. With the recent change in leadership at the Department for Education, the questions now are whether any of the developments set in motion by the previous administration will be taken forward; and which elements should be priorities.

The focus on character education was initially greeted with scepticism from some of the more world-weary members of the children's sector.

There was concern that the drive to teach children to "bounce-back from adversity" could be used by government as an alternative to doing anything about the actual adversity that children face in the first place. Ascribing this motive to the Secretary of State was, we thought, a little unfair. However, children should not be expected to find internal responses to external problems which adults have a duty to remove: poverty, discrimination or bullying to name but a few.

"Character" is one of those qualities that we would love to impart to all our children, whether we define it as the strength to carry on when things get difficult, a sense of social purpose, or a belief in one's own ability to change things. But this broad definition could also be a weakness when it comes to thinking about character as something to be developed through the education system. DfE's work has focused on extra-curricular school activities, volunteering opportunities and community engagement as a way of building character. There is nothing wrong with these things of course, but they should be part of a wider change in the culture within schools.

The work on character education should be put in the context of the noticeable shift in our education system towards emotionally healthy and respectful schools and a clear message that a child's education is about more than just exam results. Nothing showed this more clearly than the introduction of compulsory relationship and health education in primary schools and compulsory relationships, sex and health education in secondary schools, after years of campaigning by NCB's Sex Education Forum and others.

NCB is also an advocate of the well-evidenced whole school approach to mental health and wellbeing. In this approach all elements of the school contribute to promoting and supporting children's wellbeing. Such an approach would contribute positively to the development of children's character - supporting them to overcome challenges and to ask for help when needed.

Regardless of what comes next from the DfE, there remains a major legacy from Hinds' interest in the inclusion of character in schools' thinking. Ofsted's recently updated Education Inspection Framework, for example, requires inspectors to make a judgment on whether "the curriculum and the provider's wider work support learners to develop their character, including their resilience, confidence and independence".

It is clear schools will be asked questions about character for many years to come.

EXPERT VIEW

A MODEL FOR CHARACTER EDUCATION THAT CAN DEMONSTRATE ITS VALUE

By Paul Oginsky, chief executive, Personal Development Point

The concept of education starts with the notion that people have inherent characteristics and qualities that need "drawing out".

Education therefore must help each person to explore beliefs, relationships, creativity, resilience and integrity, enabling them to build self-awareness and become the best version of themselves.

Developing knowledge and skills should be secondary to the development of character. Why skill up people who have little or no integrity?

The current education system's focus on exams and league tables takes a "sausage machine" approach to education, causing poor retainment of teachers and exam stress or drop out for students.

Some excellent teachers fight for character education and act like a resistance movement in a system that does not understand what it is, how to deliver it or how to assess it. Here are some answers.

Character development happens all the time. It is when people consider their experiences, values and actions. Unsupported however, people may miss important realisations or come to ineffective conclusions. Character education is an intervention to support the character development process, supporting people to consider their beliefs and values before aligning their actions.

Teaching or preaching beliefs and values is to indoctrinate. Character education differs. It takes a catalytic approach that requires experiential learning and guided reflection.

Character education cannot be measured. Only things which have a unit can be measured; confidence, kindness, resilience and trust cannot. Characteristics can be assessed not measured. The best people to assess the change in a person's character is the person themselves and people who know them. This is known as 360° appraisal and has been used in industry for years.

Referring to character education as developing "soft skills" and considering it a side dish to exams is letting people down and doing a disservice to society. Character education must be the priority for the education system. By helping people to consider their beliefs, values and actions they can be inspired to establish ambitions and live a more purposeful life.

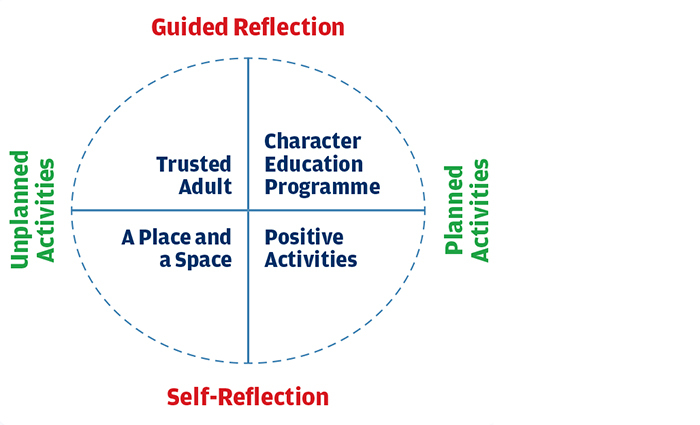

I developed a model of character education to differentiate provision and promote a shared understanding (see diagram). Its use can help avoid reductionist approaches to funding and evaluation.

No planned activities and no skilled reflection facilitator is a place and a space for young people (bottom left), character development may happen here, but character education is not being offered.

Positive Activities (bottom right), eg sports, but no skilled reflection facilitator, may have physical health benefits but may not bring about character development - sport is not character education per se.

Trusted Adult but no planned activities (top left) - a skilled reflection facilitator can introduce character education as opportunities arise.

Character education programme (top right) - the experiential exploration of a topic by utilising a skilled reflection facilitator to capture outcomes.

When funding and assessing youth provision in different corners of the grid, we must be mindful of what can realistically be achieved. Don't expect top right outcomes with bottom right funding, staffing and activities.

FURTHER READING

- The Future of Education: An Essay Collection, IPPR, September 2019

- An Unequal Playing Field: Extra-Curricular Activities, Soft Skills and Social Mobility, Social Mobility Commission, July 2019

- Education Secretary Sets Out Five Foundations to Build Character, DfE, February 2019

- Developing Character Skills in Schools, NatCen Social Research and NCB for DfE, August 2017

- A Way Forward for Character Development, PDP, August 2016

- Character Nation: A Demos Report with the Jubilee Centre, June 2015

- Character and Resilience Manifesto, APPG on Social Mobility, February 2014