A serene setting to address harmful sexual behaviour

Emily Rogers

Tuesday, July 19, 2016

Glebe House is a residential home providing therapeutic care for young people who display harmful sexual behaviour. Emily Rogers visits staff and residents to find out more about the setting's approach.

Set in Cambridgeshire countryside, down narrow winding roads, Glebe House is a therapeutic community for 15- to-19-year-old boys with a history of sexually harmful behaviour.

There is a feeling of refuge and serenity on this Quaker-run estate. Its beautiful gardens feature a wooden bridge over a rippling stream, symbolising the transition residents make. All have sexually abused other children and nearly all were abused or neglected themselves. Through a combination of therapy, community activities and education, they are helped to come to terms with their experiences and reduce risks to themselves and others. The setting is rated "outstanding" by Ofsted.

Peter Clarke, director of Friends Therapeutic Community Trust (FTCT) which runs Glebe House, can see "no rhyme or reason" behind whether boys arrive at the setting via the criminal justice system or children's services. He has seen the proportion coming from the secure estate rising to around two thirds, from around one third 10 years ago. "We're getting the same young people as 10 years ago, with the same issues, but with 18 months of young offender institution experience, making them more resistant and defensive," he explains.

FTCT was founded in 1965 to provide a therapeutic community for troubled and challenging young men struggling in care or custody. It established a reputation for working with those with harmful sexual behaviour (HSB)often accepting young people "at a point when most services wouldn't go near them", says Clarke. In the mid-1990s the organisation decided to focus exclusively on this group, working with Gracewell, a Birmingham residential clinic for sex offenders, to adapt its cognitive behavioural therapy programme for Glebe House residents.

Connor* and Thomas*, both 18, are among 14 young men currently in residence. Connor entered care at eight, after being sexually abused at home from seven. At 12, he started abusing a relative and on sentencing at 15, was referred to Glebe House as an alternative to custody, arriving 20 months ago.

Thomas arrived after six months at a young offender institution for a sexual offence, where he says he was "getting beaten up nearly every day". On sentencing, an organisation called Just for Kids Law got him referred to Glebe House.

Thomas, less than halfway through his journey here, admits he hasn't yet come to terms with his past. But he says he does now have a better understanding of what happened and how to manage socially and in relationships.

For both boys, it is Glebe House's 50-strong team of staff that set it apart from everywhere else. "They choose to work with this group and don't label you for what you've done, because they know you as a person," explains Thomas. "Lots of people in care do judge you and if you have a sex offence, you're not given hope. But here, everybody gives you that bit of hope, saying you can move on."

On referral, boys are invited here for a five-week assessment of their "containability" - whether they can safely live in this fenceless open environment - and their potential for progression and change.

If a boy is offered a place and accepts it, he stays for around two years. The Glebe House team includes seven clinical psychologists who each work with two to three residents. Each boy's treatment plan includes a weekly one-to-one therapeutic session, helping him identify the early experiences, circumstances and thought processes leading to his abusive behaviour, to reflect on the person he wants to be and address re-offending risks. Offending behaviour is tackled through weekly groups such as Cycles, based on cognitive behavioural therapy.

Each resident's progress is discussed at quarterly staff meetings, informing therapeutic, educational and behavioural targets. The young men are also involved in setting these goals. Reviews are shared with social workers, who stay in regular contact. Supervision levels are adjusted following risk assessments, and a final assessment informs each boy's "relapse prevention" plan, supported by leaving care teams and other professionals.

The community feels like an extended family, providing boys with the healthy, nurturing relationships they've often been deprived of. Sam*, 17, was previously in a psychiatric unit, where hugs were banned. Here, supportive hugs teach him about boundaries and socially acceptable behaviour. "It's a way of learning appropriate physical contact," he explains. "Sometimes I just need a hug, but have to learn which staff like hugs and which don't."

Stigma and alienation are common threads running through these teenagers' memories of care and custody. "In my care home, you could tell I'd done something massive," remembers Connor, who moved placements eight times in 11 years. "I was treated differently to everybody else, with more restrictions." A physical assault once led him to run away, something he has a history of doing.

But he hasn't run away from Glebe House and no other resident has absconded in the past five years. Connor says his treatment has helped him look into his trauma and understand it better, helped by therapy with his mother and step-father. "One of the things helping me most is hearing the views of others in the community, who support you when you've done something wrong," he says. "They say how it's affected them, so you see the impact of your behaviour."

Connor is referring to Glebe House's three-times-daily community meetings, chaired by one of the boys and attended by everyone. These gatherings are a chance to solve problems together, challenge and discuss individuals' behaviour and celebrate achievements. Staff say the meetings play a major role in residents accepting responsibility for their behaviour, an area they make "immense" progress in, according to Ofsted. "This often comes out of a mistake or significant event where they've behaved in a way that makes a community sit down and discuss it with them," explains clinical worker Kerry Lilley.

Clarke says the meetings help those who may have previously "communicated displeasure non-verbally" find their voice and see situations through other people's eyes.

Creative activities are key to the organisation's work. Glebe House has its own theatre and a thriving social enterprise called Turn the Other Chic, which sees residents up-cycle old furniture. The venture, managed by Thomas, started in February last year, after boys approached FTCT trustees for a £500 loan. Furniture is donated by homelessness organisation Emmaus, which also sells the finished products for the boys, who plough all profits into FTCT.

Getting residents to "engage with learning" is also a key goal for Glebe House, says Clarke. The "Ed Shed" is where residents learn the core subjects of English, maths and IT, alongside vocational subjects including woodwork, construction, motor mechanics, painting and decorating, horticulture and catering, leading to national qualifications. Some already have a clutch of GCSEs while others "come in with nothing", explains head teacher Michèle Hamilton Dutoit. The boys can access other subjects through distance learning and have individual timetables scheduling educational activities and therapy.

Independent living

The young men are also helped to move towards independent living. Their journey to independence starts in their second year with "Independence Week", when a group of boys rent a flat in Cambridge with staff, independently managing tasks such as Jobcentre appointments. Connor, who brims with confidence, relished the experience and since October has been in a bedsit within the main house, receiving weekly food and pocket money. Within weeks he hopes to move into the setting's self-catering bungalow, the final stage before moving out.

The lunchtime meeting at Glebe House features the Quaker circle of chairs and initial silence. Today the first item for discussion is a resident who is avoiding meetings. Clarke asks who can talk to him and Sam volunteers.

There is no hiding place at these meetings. Seemingly insignificant habits or behavioural quirks get openly challenged and discussed in line with the community's principle that every behaviour has meaning. The habits of a recent arrival are making some feel uncomfortable, including the steel-toe boots he wears inside; issues raised with him before. Clarke turns this into a discussion about relationships. "What effect do you think it has on your relationship with others, if they think you're not really listening?" he asks the boy in question.

This therapeautic work enables Glebe House residents to re-establish themselves in the outside world "not without problems, but with the right equipment to face them" according to a 2014 evaluation (see box). But despite most ex-residents not reoffending, managing in stable, unsupported accommodation and finding steady partners, the report shows most being held back by difficulties securing work. Clarke describes the need to disclose previous sex offences as a "real inhibitor to employment". "The Sex Offenders Register doesn't distinguish between types of crimes, so people could assume the absolute worst," adds project worker, Rachel Everitt. "Sex offenders have always been in a category on their own. The view out there is they're two-headed monsters."

Despite these obstacles, there is genuine optimism among boys about moving on. Connor, currently doing work experience at a diner, is confident of receiving a "really good" reference towards his hoped-for career in hospitality and catering.

Meanwhile, Glebe House is now offering a new form of aftercare known as a "circle of support and accountability", which involves meeting weekly with a group of local volunteers, each helping with an area such as employment, housing or benefits. Two or three Glebe House staff are appointed "associate members" of the circle, attending some meetings. The model has been adapted for Glebe House through a partnership between FTCT and charity Circle UK and the first circle met last month. Boys for whom this approach is not possible receive 18 months of regular support from Glebe House staff.

Recommendations from a parliamentary inquiry by a cross-party panel of MPs, supported by the charity Barnardo's and published earlier this month, will hopefully herald change for vulnerable young people like those at Glebe House. The Now I Know It Was Wrong report demands under-18s committing sex offences against children - with 4,209 such cases recorded by English and Welsh police in 2013/14 - are treated as children rather than "mini sex offenders" in an effort to avoid unnecessary criminalisation.

It calls for a working group to be established by next July to oversee a national strategy setting out consistent approaches to preventing and responding to HSB by children and improving their outcomes, alongside the introduction of training for professionals such as police, social workers, teachers and lawyers.

In the meantime, Glebe House strives to ensure its residents can go on to build happy lives.

"We see various stages of transformation," says FTCT's head of business and operations, Jeanette Hurworth. "They may start off disengaged, defensive and not trusting, but then start to believe staff do care. We see them become more robust, less fragile, more accountable. They start to believe they might have a chance in society."

*Name changed

"I FEEL READY TO PROVE TO PEOPLE I'VE CHANGED"

Tony*, aged 18, grew up without sexual boundaries. His family was "very sexual" around each other, he says: "I'd be in the room where all sorts of things would happen. I'd be there watching."

Aged eight, he started sexually abusing family members. Concerns were first raised when he was 11 and he was bailed to his grandmother's house for 14 months before being sentenced. He felt "angry, scared, embarrassed, and shocked". He was placed on the Sex Offenders Register and at 14, received a custodial sentence with a minimum of two years.

"The secure unit was not very safe and secure," Tony recalls. "You were always looking over your shoulder. Your self-esteem is low and you have very little confidence." Tony found his social worker "threatening", but was helped by child and adolescent mental health services and his youth offending team worker. He also drew strength from his grandmother's ongoing support.

His solicitor recommended Glebe House when he was applying for parole. Tony says the setting has helped him deal with the past and understand and manage thoughts that could lead to abuse. Its therapists have enabled him to "get out of the sexual headspace" and speak openly and honestly about feelings. "Relationship work was very difficult for me," he says. "But it builds your self-confidence, speaking in a big group and one-to-one, challenging people instead of getting challenged all the time."

Now at the end of his placement, Tony will be moving to a new town near home and doing a painting and decorating course at college, which he hopes will lead to employment. "I feel ready to prove to people I've changed," he says. "But Glebe House has helped me so much and I'm going to miss it."

*Name changed

THERAPEUTIC APPROACH REDUCES REOFFENDING

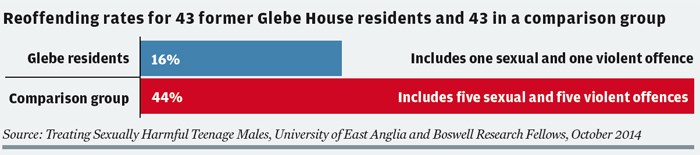

- Young people at Glebe House are much less likely to reoffend than peers with similar backgrounds in harmful sexual behaviour, according to a longitudinal study published in October 2014.

- Treating Sexually Harmful Teenage Males, by Boswell Research Fellows and the University of East Anglia, tracks the life paths and re-conviction rates of 58 residents, up to 10 years after leaving. Nearly half had criminal convictions before coming to Glebe House, mainly for contact offences including sexual or indecent assault, sexual activity or rape.

- Seven - 16 per cent - of the 43 boys who completed the Glebe House programme or left in a planned way reoffended after leaving, with 21 offences among them between 2004 and 2014. This compared with 19 - 44 per cent and a total of 95 offences - among a comparison group of 43 young people who had also been referred to Glebe House but did not become residents.

- Just one of the seven reoffenders from Glebe House had a sexual offence conviction, compared with five of the comparison group. Another had a conviction for violence, compared with five from the comparison group.

- Among the 15 boys who left Glebe House early in an unplanned way, mainly for offences or unacceptable behaviour, there were nine cautions or convictions - four sexual offences, one violent and four other crimes.

- When asked to rate various issues on scale of severity from one to five at the beginning and end of their stay, 44 per cent of the 43 boys gave a score between three and five for self-harm and 51 per cent for suicidal thoughts. By the end, self-harm reduced by at least two scale points for all 19 citing it as an issue and suicidal thoughts reduced by at least two scale points for all 22 affected.

- Three of the four young men who were assessed six and a half years after leaving Glebe House were in stable, unsupported accommodation and the same number had a steady partner and good family support, often thanks to Glebe House staff helping them strengthen or repair relationships. But just one of the four was employed. A cost-benefit analysis based on the study findings is planned.

Comparison group 44% Includes five sexual and five violent offences Source: Treating Sexually Harmful Teenage Males, University of East Anglia and Boswell Research Fellows, October 2014

]]