Adult problems made in childhood

Charlotte Goddard

Tuesday, May 24, 2016

A growing body of research on the impact of adverse childhood experiences is starting to shape the planning and delivery of services for vulnerable families in the UK. Charlotte Goddard investigates.

Screening for high cholesterol, blood pressure or body mass index is increasingly used to target those at risk of developing particular diseases or conditions. But individuals are not generally screened for "a bad childhood". This is despite the fact that a growing body of research makes it clear adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are a major public health concern, dramatically increasing the risk for health and social problems ranging from cancer, heart disease and mental health issues to obesity, imprisonment, unemployment, substance abuse, and ultimately early death.

US and UK studies have found ACEs, including neglect, abuse, parental separation or divorce and domestic violence, are very common (see below). More than half the population has experienced at least one ACE, and around one in 10 has experienced four or more. The studies also agree these have a cumulative effect: the more a person experiences, the higher their risks in later life.

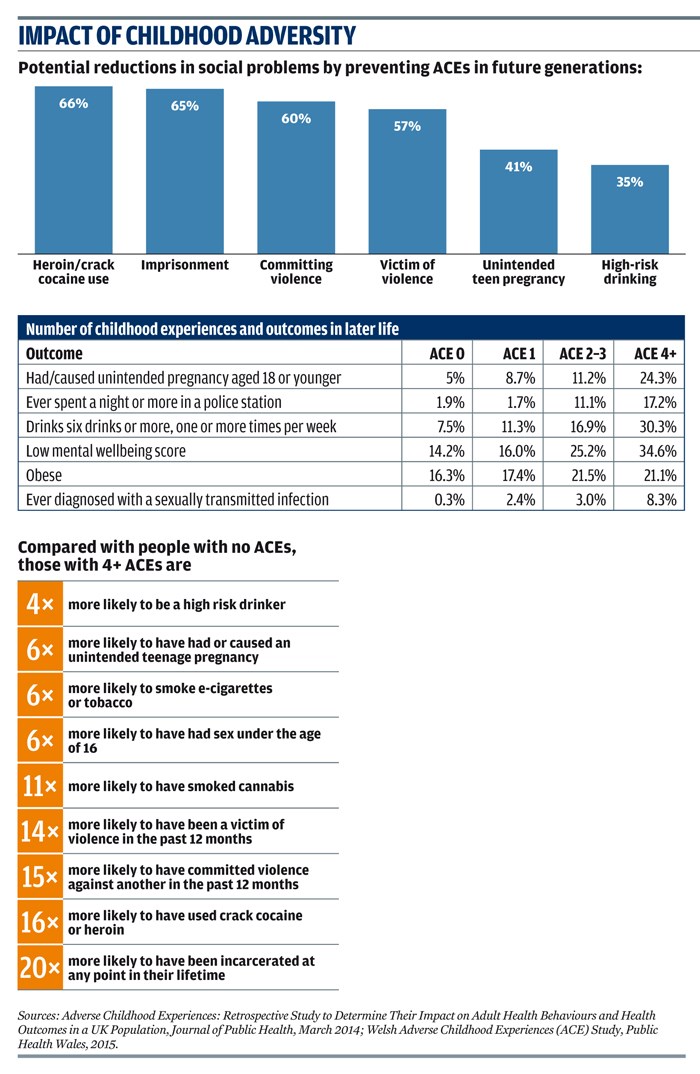

A report from Public Health Wales found people with four or more adverse experiences were 20 times more likely to have been in prison than those with none, 16 times more likely to have used heroin or crack cocaine and 15 times more likely to have committed violence against another person in the past 12 months.

"Most people understand a good start is critical to the lives of children," says Professor Mark Bellis, director of policy, research and development at Public Health Wales. "Adverse childhood experiences add empirical evidence and allow us to say it's not just nice to give children a good start in life, it has actual consequences in terms of things such as cancer, poor diet, alcohol and drug use, and depression."

The first US study took place in the mid 1990s, after clinicians investigating why some obese patients were dropping out of a weight loss programme found a significant proportion had suffered abuse as a child. Findings on the effects of ACEs is often linked to parallel research, such as that by Harvard professor Jack Shonkoff and psychiatrist Bruce Perry, showing how the stress of prolonged childhood trauma releases hormones that damage a child's developing brain and drive them towards risk-taking behaviour.

Since 2009, 32 US states have collected data about the prevalence of ACEs and associated risks. The learning from such studies is being used in practice in both health and education settings. US paediatrician Nadine Burke Harris, for example, was inspired to set up the Center for Youth Wellness in San Francisco, to prevent, screen for, and heal the effects of adverse experiences.

When patients have high ACE scores, a multidisciplinary team puts together a package of interventions, such as home visits, mental health care and advice and support on nutrition, as well as educating parents about the impact of childhood trauma.

Meanwhile, in Oregon, a law established in March this year will introduce a "trauma-informed approach" to increase school attendance rates, reduce trauma and promote resilience. The programme will include training for school staff around ACEs, co-ordination with health and community services, and the appointment of a "trauma specialist" to oversee the plan.

Although it has not been taken up across the board, increasing knowledge of the consequences of ACEs is driving policy and practice in the US. But what of the UK, where such research is relatively new?

Karen Hughes, Professor of Behavioural Epidemiology at the Centre for Public Health, Liverpool John Moores University, is part of the team that has carried out research in England and Wales.

"Before we carried out the research, we had no idea what the level of adversity would be, since the original US study is based on a sample of those using health insurance while our sample is more diverse," she explains. "It is revealing that half the population has experienced an ACE, and the consistency of the relationships between ACEs and poor outcomes is clear."

Services are starting to take research findings into account. "There is a key argument for tweaking universal services to recognise the ACE issue," says Hughes. "This is beginning to take place, as women are asked about alcohol consumption in pregnancy for example, and it's about integrating things like that into more routine and structured systems."

Blackburn with Darwen Council is a frontrunner when it comes to using the research around adverse childhood experiences to drive policy and practice. The authority commissioned Lancashire Care NHS Foundation Trust to develop a screening tool, Routine Enquiry about Adversity in Childhood (Reach). This enables practitioners to identify adults with high ACE scores and support them through targeted interventions, helping them provide safe childhoods for their own families. Early intervention staff were trained in this approach in 2013 and the training has now been extended to other sectors including health, voluntary and community agencies.

Holistic approach

The next step is to incorporate this individual, adult-targeted screening model into a more holistic, universal approach that aims to prevent children from experiencing trauma in the first place, or lessen the effects of such experiences if they take place.

"Reach is one tool within a whole culture change," says Dr Helen Lowey, consultant in public health at Blackburn with Darwen. "This has to be a whole system approach, not just a clinical individual intervention. Reach complements a broader ACE agenda."

This broader agenda is currently being pursued in a pilot, Embrace (Emotional Building of Resilience to overcome Adverse Childhood Experiences), which aims to create "ACE-aware schools". The thinking is that children exposed to stressful situations at home or within their communities are constantly in "fight or flight mode", which results in them being unable to think rationally or learn.

"It's about making all the staff and pupils ACE-aware and understanding how adverse experiences impact on behaviour and learning abilities," says Dr Lowey.

ACE-aware schools will prioritise building resilience in all pupils. "We will use the ACE approach as a way of thinking about strategies that a school can put in place to change all the children's behaviour," explains Dr Lowey. "Singling them out isn't necessarily the most appropriate way of dealing with it."

Schools might, for example, introduce nurture groups and encourage teachers to ask questions such as: "Are you OK? This doesn't sound like you." Schools might run activities around building attachment, learning about emotions and how to express them in a healthy way, acting rather than reacting and making good choices.

Blackburn with Darwen is also building ACE awareness into its commissioning process, starting with substance misuse services and sexual health services. "We are working through with providers what ACE awareness means in this context. What does it look like and how can we change service provision from within to support the consequences of childhood adversity and get to the root causes?" she says.

In Wales, learning around ACEs in the Welsh population (see box) is being incorporated into policy and practice, particularly around how agencies work together. The South Wales Police and Crime Commissioner has adopted early intervention as a key principle and has signed a memorandum of understanding with Public Health Wales. "We are carrying out joint work looking at training police so they are ACE-aware and capable of providing an initial response if faced with someone with a legacy of adverse experiences," explains Bellis. "We are in the very early stages of putting the team together, but will be working on assessment tools, and referring on to other services will be part of that."

Bellis cites programmes such as the Family Nurse Partnership, Welsh early years programme Flying Start, and parenting classes such as Triple P, as examples of early intervention programmes drawing on ACE awareness. "I wouldn't say those programmes are fully there yet," he says. "A lot of programmes talk to parents about the importance of early years, but don't necessarily talk about how the activities of parents can have a lifelong effect on their children and impact areas they wouldn't think of, such as cancer and heart disease."

Parts of the sector are more aware of the ACE research than others, agrees Jon Brown, lead for tackling sexual abuse at the NSPCC. "It doesn't get enough airtime," he contends.

The NSPCC runs a number of programmes "informed by the whole notion of adverse childhood experiences", including Thriving Families and Baby Steps. "It's about the importance of understanding adults, antecedent history and the quality of their attachments - how to ensure maladaptive and potentially harmful behaviour is not transferred onto babies and young children," says Brown.

Thriving Families recognises neglect can seriously affect the physical, social and emotional development of children from birth onwards. Families are assessed and offered support according to their needs, including parenting classes. Baby Steps is an antenatal programme that aims to lessen ACEs by supporting vulnerable parents before the baby arrives. Parents are visited at home in the seventh month of pregnancy and offered six weeks of group sessions before the baby is born and three more afterwards. Groups are led by a children's services professional and include films, group discussions and creative activities, with a strong focus on building relationships between parents and their babies.

"The voluntary sector does tend to be at the centre of innovation, because the statutory sector is under such pressure in recent years trying to focus on absolute necessities," says Brown.

However, the statutory sector may be set to become more ACE-aware with the development of the government's Life Chances strategy, due to launch later this year. Specifically drawing on research into adverse experiences in early years, the policy announced by the Prime Minister in January, is being overseen by the Cabinet Committee on Social Justice and will include elements such as parenting and mental health support.

"The Life Chances strategy appears to turn towards a greater awareness of the quality of experiences in early years, with funding for more parental support and relationship support between parents," says Keith Davies, associate professor at the school of social work and social care, Kingston University, and editor of the book Social Work with Troubled Families. "In his speech, the Prime Minister particularly referred to research about the quality of parenting in early years and made specific references to mental health, addiction and domestic violence. This seems to reflect a shift in the direction of ACEs being something the government is concerned about."

The Troubled Families programme was set up initially to combat antisocial behaviour, but looks set to become a vehicle for acting on these concerns. "In its first phase, it was more driven by the desire to combat antisocial behaviour but as it expands the government has said it needs to take on an increased awareness of the quality of parenting," says Davies.

It seems understanding of adverse childhood experiences is making its way into national policy and practice. The hope is that it will lead to more children protected from experiences that can affect not only their lives but the lives of their own children.

RESEARCH EVIDENCE ON ACE

The original ACE study is theCDC-Kaiser Permanente Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study, which took place between 1995 and 1997 in Southern California. More than 17,000 people receiving physical examinations were questioned about their childhood experiences and current health status and behaviours. Respondents were asked about 10 adverse experiences in their early lives, in the categories of abuse, household challenges, such as domestic violence or parental separation, and neglect. Almost two-thirds - 64 per cent - of participants reported at least one ACE, while 12.5 per cent reported four or more ACEs. The study found that the more ACEs a person experienced, the more likely they were to be at risk of poor health, including seven of the 10 leading causes of death in the US. More than 50 journal articles have since been published, following up the research findings and linking ACEs to a long list of negative outcomes including alcoholism, depression, poor academic achievement and financial stress.

cdc.gov/violenceprevention/acestudy

Researchers at Liverpool John Moores University's Centre for Public Health surveyed 1,567 people in England in 2012. They found 47 per cent reported at least one of 11 different ACEs and 12 per cent reported four or more. The most common was parental separation at 24 per cent, followed by verbal abuse at 20 per cent. ACEs were found to have a cumulative effect and correlate with worse outcomes for health, education, employment and involvement in crime. The fact that people with ACEs were more likely to be drawn into crime, violence, have early unplanned pregnancies and remain in poverty, meant they were also more likely to perpetuate a cycle exposing their own children to ACEs.

jpubhealth.oxfordjournals.org/content/36/1/81.long

A Welsh Adverse Childhood Experiences study was published in 2015 by Public Health Wales. This research found just under half - 46.5 per cent - of all 2,028 individuals surveyed had experienced at least one out of nine ACEs before the age of 18, while 14 per cent had experienced four or more ACEs. The most common ACE was verbal abuse at 23 per cent, followed by parental separation at 20 per cent and physical abuse at 17 per cent. Those with four or more ACEs were more likely to report adult behaviour harmful to health, such as drug abuse. The study looked at the benefit of preventing ACEs and found this could reduce levels of heroin and crack cocaine use by 66 per cent, imprisonment by 65 per cent and unintended pregnancy by 41 per cent, among other things.

www.wales.nhs.uk/sitesplus/888/news/40000

Further study

Further work is needed to understand what works when it comes to preventing ACEs. Some children with adverse experiences do not go on to develop negative outcomes, and researchers are interested in studying the factors that make them resilient. The NSPCC's Jon Brown says the organisation has commissioned research into the economic cost of all kinds of child abuse, with findings available later this year.